From a never-runner to an ever-runner, from 0km until 2017 to nearly 3,000km in 2020, it has been a unique journey that also helped PRASUN SONWALKAR deal with the grim days of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Every runner has a story; mine begins with being diagnosed with pre-diabetes in Bristol in 2012, not taking it seriously for years because it didn’t feel any different, and after moving to London in 2014, reaching a tipping point in June 2016: the day my wonderful GP looked at my ‘very high’ blood test results, shook her head, and said with the hint of a wry smile: “If you continue like this, I will have to put you on insulin”.

The telling-offs that hit the hardest are those that are delivered subtly. After decades of an irregular lifestyle in journalism, something had to give, much had to change. One can lead a perfectly normal life on insulin, but somehow to my mind having to inject it into the body every day meant the ultimate failure of effort to put the disease into remission, if not reverse it.

Diabetes is one of the fastest growing diseases in the UK, India and elsewhere, leading to life-threatening complications and early death. If you are of Indian/Asian ethnicity, you are told from every direction that you are at a higher risk of contracting diabetes due to genetic and other reasons. I knew I would get it (mother had it), but when diagnosed in 2012, a doctor-friend said ‘pre-diabetes’ is a misnomer; best to proceed on the assumption that you have it and work on dealing with it. Central to any effort to deal with Type 2 diabetes is losing weight by regular exercises and changing food habits. Years went by after the diagnosis, but it still didn’t feel any different or worse, though the blood test results kept shooting up and dangerously north.

After the GP appointment that day in June 2016, I walked out of the surgery a much chastened man; things could not continue as they were. The difficult journey to deal with the lifestyle disease had to begin, and it began the same evening with baby steps. Pushing against inertia and mental blocks, I walked for almost an hour, for the first time in decades. It was the first day of a new journey of trying to walk as briskly as possible. The goal, reference point I ambitiously set myself was ‘drench’: I must return home drenched in sweat.

Increasing the pace and distance slowly by the day, and combining it with changes in diet, I soon noticed minor gains in weight loss and overall feelings. Despite growing niggles in the legs and elsewhere, it felt good walking briskly along the sylvan spaces near my house, taking in the fresh air, and returning home for a warm bath. After some weeks of brisk walking, I wondered if it might be possible to jog slowly for about 100m, from this house in the lane to that – how bad could it be? It turned out to be so painful in the calves and the right ankle that it needed a visit to a podiatrist and change of shoes. But as days went by, I tried to increase the distance and duration of the slow jogs; from this set of traffic lights to that; from this gate to that bend; from this parked car to that van at the end of the lane.

I eventually managed to slow-jog for continuous 5 minutes in the walking hour, trying best to tolerate pain in the legs and quads. This slowly but eventually progressed to jogging for 10, 15 and then 30 minutes in the walking hour, and more, until the app on my phone one day showed a total of 8km covered in the hour. The sight of a middle-aged man trying to run on the streets of London must look weird; it prompted a range of reactions from pedestrians and others, but the world of running beckoned and I began enjoying it.

The threshold of pain tolerance went up considerably, as I noted more gains in weight loss, accompanied by a rare feeling that I could not put in words. Many call it the ‘runner’s high’, but no one has quite adequately described it. The kinesthetic kick one gets while coasting on a steady, rhythmic run, hitting the right spots pain-free, grounded fully in the moment is almost akin to meditation, taking you into the zone where you feel the flow and lose a sense of time, with the mind uncluttered, almost blank, open to new impulses.

At times I pushed through excruciating pain in the early phase of the routine. One day, I felt something snap in the left calf and hobbled in much agony into the A&E, where doctors thought it could be a case of varicose veins. They quickly put me through tests, but concluded that it was a tear in the calf muscle that would heal in a week of rest. There have been several such minor mishaps with pain in newer areas of the body that laid me low for some time, but eventually managed to return to the routine, driven by the GP’s words and the imperative of having to deal with the Big D – you reach a stage where you just don’t have the luxury of choice to take it easy.

By mid-2017, I was doing around 12km at a pace of nearly 9km/hour, almost every day. One evening, on a wild impulse while surfing the internet, I entered a half-marathon event in Windsor, my first. Before the event in November, I went on a trial run and managed to run the 21km distance around my usual route. But after 2 hours and nearly 30 minutes of exhaustion and utter pain, I couldn’t see why people put their bodies through the ordeal. The dread and pain, however, soon lifted as endorphins and the prospect of actually being able to complete the challenge took over.

On the day, running the half-marathon around Dorney Lake in Windsor was a pain but also a revelation. There were hundreds of people at the carnival-like event; my son had to ask me to moderate my excitement. Lining up at the start, it was sobering to see people much older but fitter than me. I took off with them, running the first 5km trying to keep pace with the keen ones, only to crash, burn and stop by the wayside, realising the enormity of completing the 21km challenge.

Experienced runners sped by, some slowed down to encourage me not to give up. I somehow managed to jog-run-stop, jog-run-stop around the lake until about 15km, when all energy reserves dried up and the legs with a mind of their own stalled, simply refusing to take another step. An elderly lady, who was fitter and running faster than me but was apparently aware of my troubles, came by and loudly called out to me sternly: “Keep going, KEEP GOING”. At that perilous moment, she reminded of my English teacher in school, who I feared much. To this day I have no idea where the frozen legs found the energy, but I promptly took off, finishing the half-marathon in 2 hours and 9 minutes. I later met the stern but friendly lady, thanked her, and learnt that she is an experienced runner.

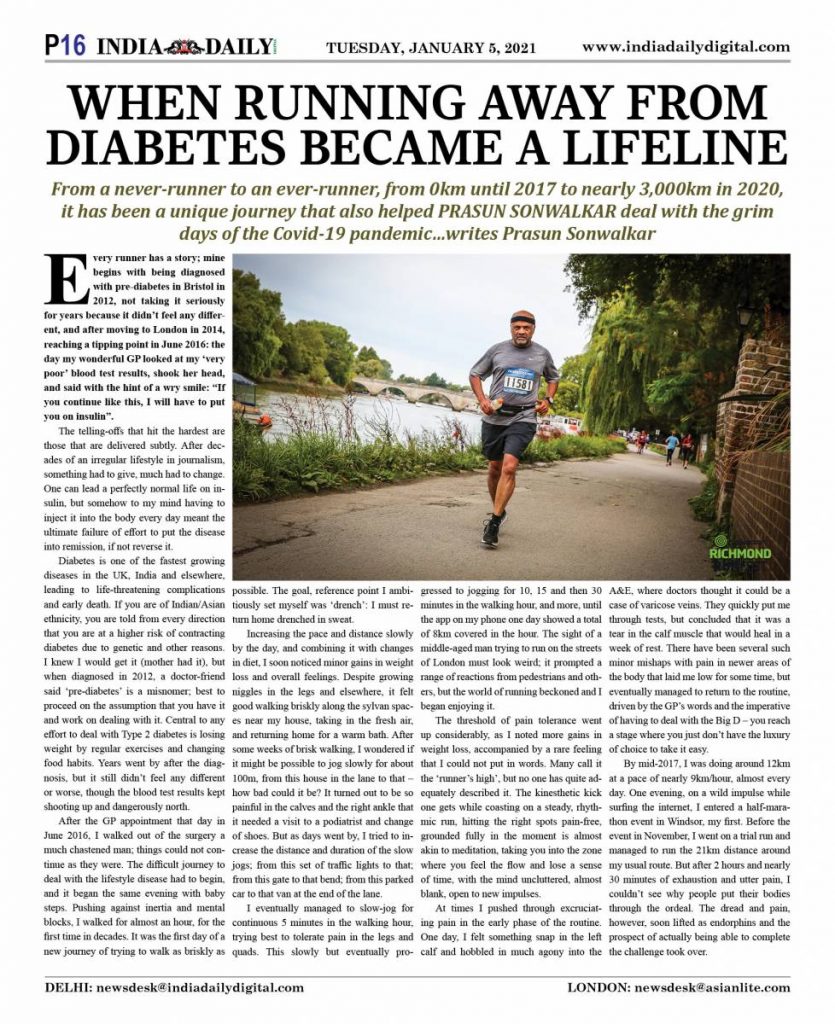

I have since run the Paris Marathon, two Richmond Marathons and several half-marathons. The finish times were not great, but I was glad to complete them at my age: the first in 5.48, the second in 5.24, and was on course to complete the third within 5 hours, but around 37km, 5 km from the finish line, tripped, fell facedown, and gave up more due to the shock than to injury. Thanks to the gains made in regular runs through lockdowns in 2020, a finish in 4.30 may well be a possibility when marathons resume in 2021 (the plan was to run at least two marathons a year, but they were cancelled in 2020). I stopped entering half-marathon events, since the long-run on a weekend day usually amounts to the half-marathon distance or more.

In between, for nearly two years, I went through incredible levels of pain from plantar fasciitis in the left foot that several physiotherapists who charged me thousands of pounds and got me to buy things that proved useless could not resolve. I ran the three marathons pushing through this extreme pain, through the much-feared ‘wall’ you encounter around 30km. After much research and trying out many options, I found a way to substantially reduce the pain in mid-2020.

The baby steps eventually added up. From the ‘very high’ HbA1c reading in June 2016, it dropped to ‘excellent’ in mid-2017, remained there since, and the latest ones placed me in the ‘normal’, non-diabetic zone My GP is rather pleased. Much has changed since the 2012 diagnosis, but the larger challenge is to sustain the running routine in the future, because any let-up will send the test results north again and diabetes will return.

You learn a lot about your body when you begin a new routine to deal with a health crisis. From a lethargic, total antithesis of a runner, to one who now runs at least 15km/day, at least five days a week, my body went through various phases: it complained, threw tantrums and rebelled, but finally adapted to the new demands. The real challenge lies in staying the course and pushing through the first couple of weeks of severe pain – after that, the pain dissipates. It is as much to do with the mind and willpower as with the body’s ability to adapt.

Running is now a permanent feature of everyday life. In the early days, when friends learnt of my new interest, it generated some mirth and the warning: “What’s wrong with you, be careful of your KNEES”. But after nearly four years of pounding the ground, my knees are no worse; in fact, there is new research that says running helps prevent damage to knees. I found several fascinating accounts and tips in the rich discourse of running in training videos, books, films, experiences of others, discussions in running groups, including Nick Cohen’s column on how running saved him from booze lunches and obesity. It led me to Haruki Murakami’s memoir, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, which is a delight. Of course, it is OK to hate running, as Seamas O’Reilly writes, but so far I have not reached the stage of hating it. You listen to your body. There are days when I just don’t feel up to it and don’t run, but have never hated it. I have always gone out and returned with life-sustaining feelings, drenched in sweat, looking forward to the next day. I don’t carry earphones, but some evergreen Bollywood melodies play on the loop in the mind, as the legs try to keep to their rhythm.

Running also led to awareness of the growing number of runners on the roads and parks, and of the wider world of running; a Facebook group I joined has over 32,000 members. The more time I spent reading about it, acquiring a range of shoes, clothes and accessories (not cheap), the more I realised that it is a thriving sub-culture across the globe. I picked up new words, codes and names of body parts I was unaware of: pronation, plantar fascia, dorsiflexion, supination, gluteus medius, shin splints, PB: personal best, HR: heart rate, VO2 max: maximum rate of oxygen consumption, cadence, TE: training effect, and so forth. Running is also a multi-million pound economy – check out the large exhibitions and stalls before marathon events, or the thousands of websites on shoes, nutrition, watches, gait analysis, clothes, accessories, ways to prevent injury, coaching and so forth.

I also discovered the real meaning of ‘marathon’, a word long taken for granted. Its history in Athens and the town of Marathon sparked the ambition to some day run the original route. I was also unaware of the marathon distance: 42.195km; and the half-marathon, 21.097km. Since 2017, when the running bug struck, most of my off-work time went into research into running: about UTMB, ultra-marathons, Eliud Kipchoge, Paula Radcliffe, Roger Bannister, Mo Farah, the Tarahumara runners, Shivnath Singh and Milind Soman. There was a time when I couldn’t quite see the point or challenge in running and athletics, but now keenly look forward to live coverage of marathons and study the splits of winners.

During the lockdowns and through most of 2020, limited social interaction led to an existence almost on autopilot; running helped to break free from the logjam. Also, lockdown rules allowed outdoor activities, and experts announced that there is very little risk of being infected while running and passing by others at some pace on roads and in parks. Throughout the grim days, weeks and months of 2020, I continued the earlier established routine and improved, clocking over 300km/month for many months, adding up to nearly 3,000km during the year.

I came to running via diabetes and became an enduring passion. From a never-runner, it has been an unlikely journey through phases of pain and gain to reach a stage where not only is diabetes on the path to remission, it also improved overall health. The GP’s subtle knockout blow in June 2016 worked, am glad diabetes happened when it did, and that I was at an age when it was still possible to find a wonderful way out.

(Prasun Sonwalkar is a London-based journalist)