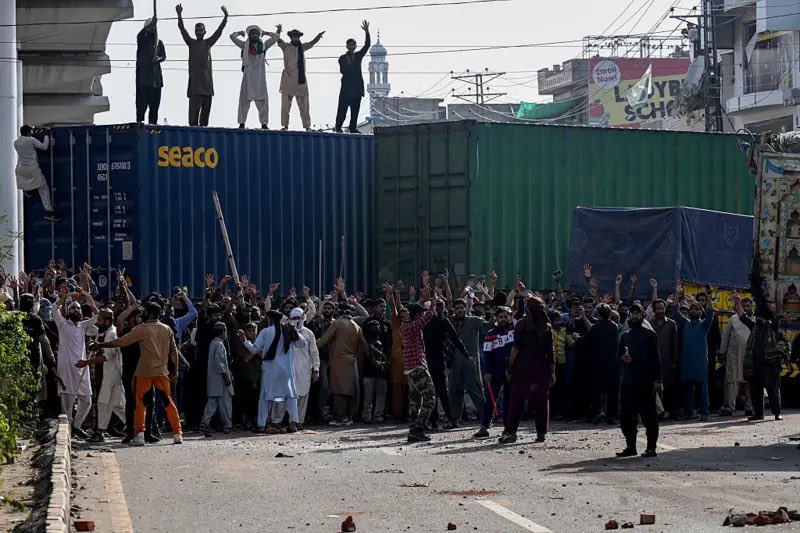

Leaving their homes and hearths in desperation, the refugees, mostly poor and deprived men, women and children, look for safety of home and livelihood….reports Asian Lite News

A huge and difficult-to-surmount crisis stares at Pakistan in the form of refugees from Afghanistan since the advent of a friendly regime that has caused much exultation among the government and the people alike.

This may momentarily divert attention from the Covid-19 pandemic and economic misery. But contributing to and compounding them is the growing number of refugees coming in, which neither the Pakistani security forces nor the incomplete border fencing can effectively control.

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), Filippo Grandi, visiting Islamabad last week urged Pakistan to take in more refugees. But Pakistan, even as the influx soared last month, said that it simply does not have the capacity to take more. It has refused to set up more refugee camps.

Analysts basing their views on past records say that Islamabad’s pleas may cause the world community, both the governments and the NGOs, to send in funds. But those millions, while providing succour to the refugees, get diverted to other projects, and become a cause of corruption and do not change the situation on the ground.

Quoting local sources along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, Al Jazeera (September 2) reported that, for weeks, up to 5,000 Afghans had been crossing daily until August 15, the day the Taliban took control of Kabul. That number has since doubled.

Leaving their homes and hearths in desperation, the refugees, mostly poor and deprived men, women and children, look for safety of home and livelihood. By the very nature of their movement, they take away space and jobs of Pakistanis who naturally resent them.

Besides social and economic tensions, there are also issues of drugs, crime and disease. Afghanistan is the world’s largest producer of opium.

The ethnic problem also raises its head and exacerbates the dispute with Afghanistan that is as old as Pakistan’s creation in 1947.

The existing British-demarcated border, called the Durand Line after the man who drew it, is not accepted by any regime in Kabul, including that of the friendly’ Taliban, because it restricts the movement of the Pushtuns. Afghans consider areas under Pakistan as theirs, which have been wrongly taken away.

A continued influx of the mainly ethnic Pushtuns from Afghanistan, experts say, could weaken the Durand Line and make it that much more difficult for Pakistan to govern and control large swathes of tribal land that has always remained ungoverned or loosely governed.

It is here that those opposed to either Kabul or Islamabad, or both, take shelter and operate at will. This is the region where Osama bin Laden managed to hide for long, and this is also the place where the Al Qaida and ISIS-Khorasan have thrived. Thus, Pakistan has more than its handful to handle while acquiring what its experts call the “strategic depth” vis-a-vis its eastern neighbour, India.

Today, Pakistan is home to more than 1.4 million registered Afghan refugees, many of whom entered the country some 40 years ago, after the Soviet invasion in 1979. Hundreds of thousands more joined them after the US invasion in 2001. Many of them came as refugees in the 1980s.

By 2002, the UNHCR had counted three million Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Many returned to Afghanistan and the numbers dropped until the US troop withdrawal began this year.

Pakistan’s government insists that it is unprepared for a refugee influx and is considering options for how best to manage the new arrivals. After negotiating the crossing, most refugees make their way to Pakistan’s main urban centres, seeking shelter, safety and, in some instances, the means for an onward journey.

In a bustling corner of Karachi, a sprawling metropolis of more than 20 million people in southern Pakistan, a sizable Afghan community has lived for decades.

Many of them came as refugees in the 1980s. Behind the narrow, broken streets near the city’s largest bus terminal, the neighbourhood is covered with low-rise apartment complexes, the roads choked with motorcycles and bicycles. In the corner of one such apartment compound, there are several homes with their doors wide open.

Returning to Afghanistan is not easy. Some of them have just made their way from Afghanistan. They had to brave violence and risk being turned away or get arrested at the security checkpoints as they fled a country in the throes of transition. It is a journey some have endured before. This is the second time they became refugees. Some, who have refugee ID cards issued by the Pakistani government, know that they will have certain rights and protections guaranteed in their host country.

The situation post-Taliban 2.0 is far from settled, making things more complex, especially when Western media reports allege that Pakistan has played a partisan role in the Taliban victory. The conditions are volatile.

Hence, on the fresh refugee influx, the UNHCR chief Filippo Grandi has suggested that if these refugees are sent back due to the lack of documentation, they may be at risk. These refugees might be from ethnic minorities or they might have other issues.

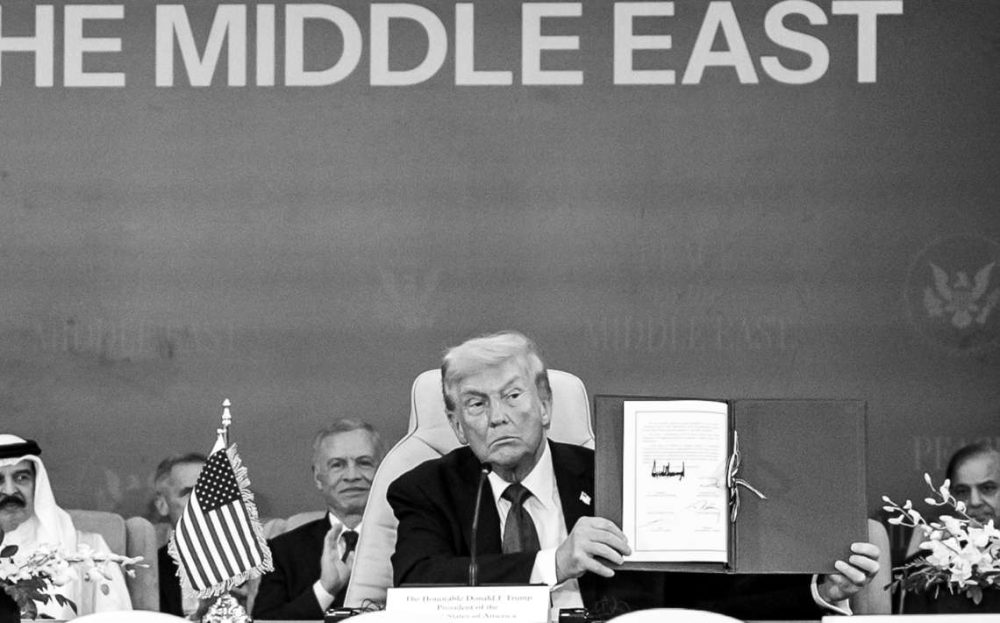

Grandi said the future is full of uncertainties and risks, but it is important that “we in the international community continue to engage with the Taliban in order to go forward and save Afghanistan and the region from disaster”.

If the state ceases to function, in both Afghanistan and Pakistan, “it will provoke a crisis much bigger than the humanitarian crisis”, the Dawn quoted him as saying.