Hindi films completed and waiting for cinemas to reopen helped some of these platforms. Seeing that the wait could be endless, the production houses decided to premiere the films on OTT platforms…reports Asian Lite News

Netflix laments low subscription base

OTT platforms started in India around 2013-14 with Reliance, Zee, etc. launching a kind of online service for entertainment. Available mostly on mobile phones, but little was known about them and smart phones had yet to catch up.

The major foreign platforms followed a little later, around 2016. Netflix was much talked about among those with buying power. Some liked to boast about being hooked to Netflix! To the others, it did not matter because they did not know what one was talking about. To debate or discuss anything, both sides need to know the subject. The subscriptions were slow to catch up.

People got interested when these platforms started producing or outsourcing specific programmes exclusively for Indian viewers. Netflix was a new entity as far as India was concerned, but other platforms such as Sony, Star, Disney and Zee, though new to OTT, were already familiar brands and people in India kind of knew what to expect from them.

What is more, be it Sony, Zee or Star, they already had an ample repertoire of Indian entertainment, especially Hindi content. Similarly, Eros Now is also an old hand in the film business. Shemaroo Me, the late entrant to the OTT field, is an old hand having started with a video library in the name of Shemaroo and later, the video rights acquisition and distribution business. They believed in buying the rights of films from big-name production houses and today boast of one of the best collections.

Since then, the number of OTT platforms has mushroomed. Many new names sprang up. The Covid-19 lockdown imposed in March 2020 proved to be an opportunity for these platforms. Cinema theatres were ordered to close down, which only added to the OTT count.

To an extent, even the OTT managements were taken unawares. Shooting for films as well as for television and OTT platforms were forced to stop. Television channels, which have banks of ready episodes, managed for a few weeks, but eventually had to resort to reruns. OTT platforms had no such backup. So, they had to fall back on films and both Indian and foreign as well as international OTT streaming content. That kept them going.

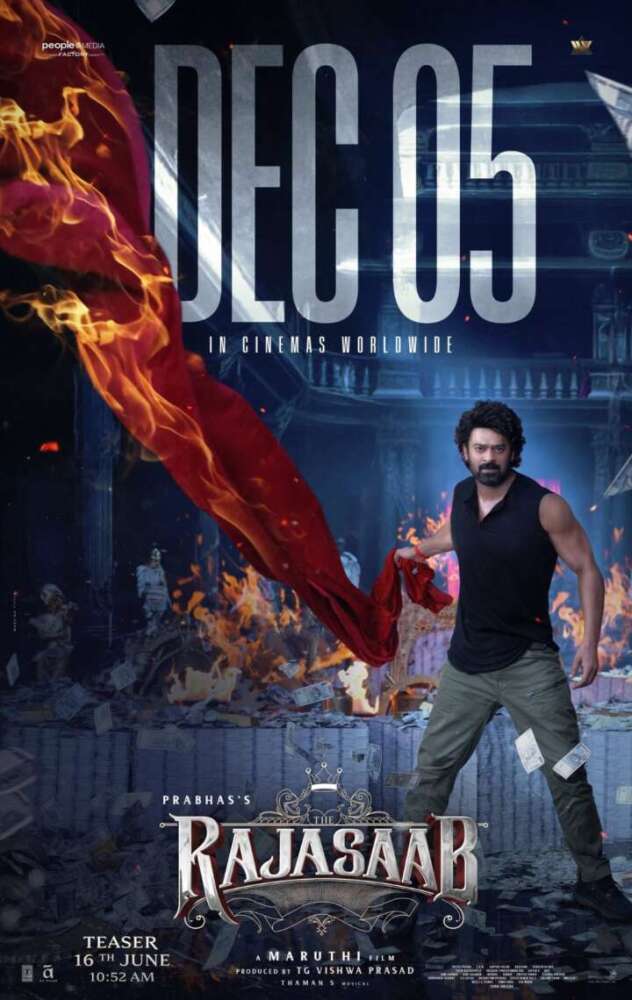

Hindi films completed and waiting for cinemas to reopen helped some of these platforms. Seeing that the wait could be endless, the production houses decided to premiere the films on OTT platforms.

Films such as ‘Radhe’, ‘Gulabo Sitabo’, ‘Laxmii’, ‘Ludo’, ‘Sherni’, ‘Hungama 2’, ‘AK vs. AK’, ‘Coolie No. 1’, ‘Tribhanga’, ‘Sadak 2’, ‘The Girl On The Train’, ‘The Big Bull’, ‘Toofaan’, ‘Mimi’, ‘Shershaah’, ‘Bhuj: The Pride Of India’, ‘Bhoot Police’, ‘Rashmi Rocket’, ‘Sardar Udham’, ‘Hum Do Hamare Do’, ‘Dhamaka’ and ‘Bob Biswas’ were released on OTT.

Though most of these films were not appreciated, at least, they sated the curiosity of some, especially the self-styled critics, who like to talk films and rate them with stars.

Not all OTT platforms may be doing well or even getting subscribers. Some may vanish into thin air just like they popped up from nowhere.

But the one that is feeling the pinch is the pioneer international content streaming platform, Netflix. The company feels that it has not got the required subscription base in India, it has not been successful in India. One of the factors that was a deterrent for the masses was the high monthly subscription plan of Rs 499, which the company has set right now by reducing it to Rs 199.

Till not long ago Rs 499 amounted to a month’s subscription of a local cable network with a number of channels, provided that you never bothered to count or surf along with the regular ones in demand. With a choice of multiple OTT providers, forking out almost Rs 6,000 per year was a tough call for the middle class, which spelt a bigger base.

The best example would be Zee 5 and ‘Radhe’. The platform decided to make the most of the opportunity of the Salman Khan film premiering on OTT by offering annual subscriptions at a much lower price, Rs 499 (earlier 799), which included an eight- hour window to watch ‘Radhe’! This was used as an instrument to broaden the viewer base of the platform.

Besides, Netflix is seen more as an elite platform for niche viewers with a huge collection of international programmes, but not much in comparison for the regional language viewers. Netflix has a reason to worry about its subscription lag, which is 5.5 million, against Amazon’s 19 million and the top draw, Disney+ Hotstar’s over 45 million.

Mobile phones and air travel, for example, had a limited number of takers for a long time. A basic ‘dabba’ mobile phone cost more than Rs 15,000 and the call rates were Rs 16 per minute with both parties, caller as well as receiver, billed. What happened was that the phone was used more as a pager as people checked the number and called back from landlines.

Then came the budget airlines and a range of mobile phones suitable for all pockets. One can see the difference. Airports are now overflowing with travellers and a mobile phone adorns just about every pocket.

In India, with its vast consumer base, if you wish to go for volumes, you have to be pocket friendly. That is when you build a mass base.

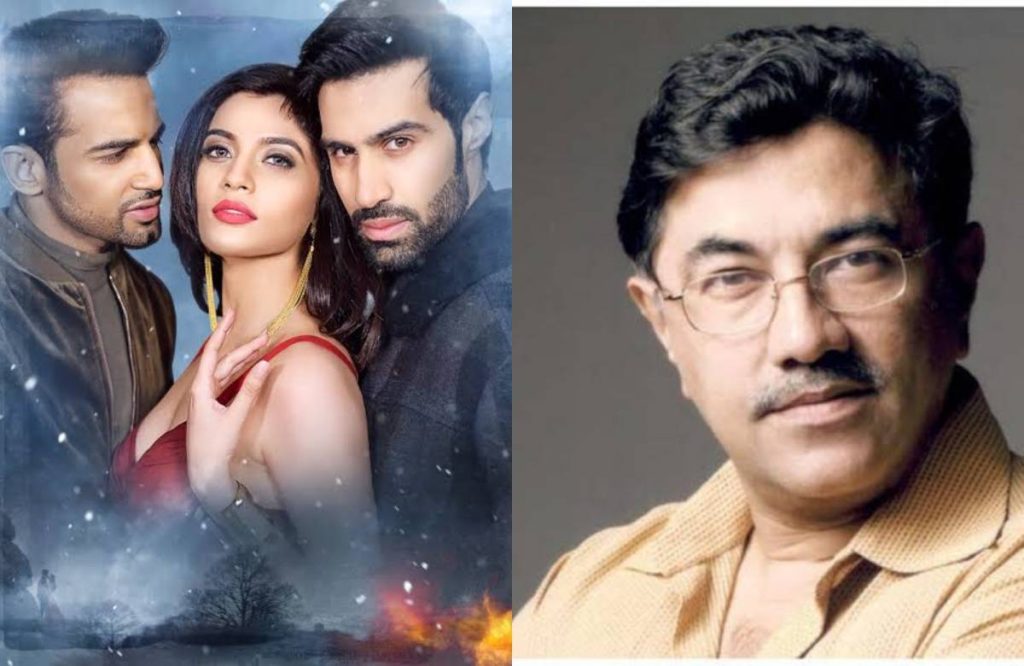

Producer Suneel Darshan Sues Google/YouTube/Sundar Pichai

YouTube plays thousands of movies, songs and other such content and the number of hits the Indian film and songs get on this platform is amazing. These contain a lot of old films, for, in most cases, nobody seems to know who holds the copyright of such content.

It is the responsibility of YouTube, though, to ascertain and trace the owner of the copyrights before it starts adding any content on its platform. Or at least the platform should inform the parties concerned through a Public Notice in the media as is the trade norm.

When any content watched by a viewer earns a hit, the score is readily available and the platform should have devised some sort of mechanism to deposit the monies so earned with a producers’ body or a trust. That money certainly does not belong to YouTube.

The film business ran on trust for a long time. Even if a producer and his actors had decided on the price to act in a film (there were no other terms, actually), then nothing was put on paper. The agreements were drawn only after the release of a film or when it came to filing income-tax returns! Similar was the practice with distributors and other technicians.

But, as the entertainment industry broadened its base with the arrival of television and video rights, the filmmaker learned at some cost the need for an agreement. Video and satellite channels, while drafting agreements, included what were called ‘Tunnel Rights’, which meant that all rights that may arise from future developments and technology would belong to them!

The producer, working on borrowed monies, signed away just about everything!

When the video format came to the market, many producers were surprised to see their films available in the format. How did it happen? Many prints of Hindi films were lying in the warehouses of overseas distributors, which were acquired by the video companies at a price of as little as Rs 10,000. One Hong Kong-based label specialised in this kind of business.

The producer had neither the inclination, nor the resources to go fight a case in a Hong Kong court. This is akin to what Suneel Darshan states about Google/YouTube. Who will take on such a monstrous entity? Be it a monstrous entity such Google, or other similar players, or even the video pirate at the local level, the producer is left to fight a lone battle.

There is no record of any producers’ association joining forces with him, the very thing these associations are meant for: to protect the interests of their producer members.

Suneel has sued Google, YouTube and CEO Sundar Pichai for the infringement of the copyright of his film, Ek Haseena Thi Ek Deewana Tha. Suneel’s film is available on YouTube and has been uploaded by people other than Suneel himself.

So, does the royalty go to them? Does YouTube ask for any sort of proof of ownership of copyright before uploading a film? If not, the channel is encouraging fraud and piracy.

Suneel states that he wrote many mails to YouTube but got no response. Now this is rude and taking Indian people for granted. Finally, Suneel Darshan had to take recourse to the court of law. Now, besides whatever other observations that the court may make, YouTube needs to be told sternly that it is answerable.