Bano’s mujraghar, in one of the most important markets of Jaipur, overlooks the streets that are a rush of houses and tourists buying clothes, savouring food, and haggling with rickshawalas…reports Punita Maheshwari

Zubeida Bano started performing mujra at the tender age of 18. Now 70, chewing her supari and clad in a plain pathani suit, it is difficult to believe at first glance that she is a trained dancer. However, one only need to spend some time in her mujraghar to notice the ‘ada’ (style) with which she walks, how she sits with authority on her gaddi, and her deep eyes that reflect memories of an age-old tradition, and understand that she has been a part of rich cultural history.

Her mujraghar is one of the 20 at Jaipur’s Chandpole Bazaar. Her authority seems to come from three areas: her pride in keeping an old dance form alive, her ownership of the mujraghar, and her own memories.

You know the mehfil is about to begin when you start seeing Bano and many older and former tawaifs (courtesans) step into their mujraghars to begin the performances.

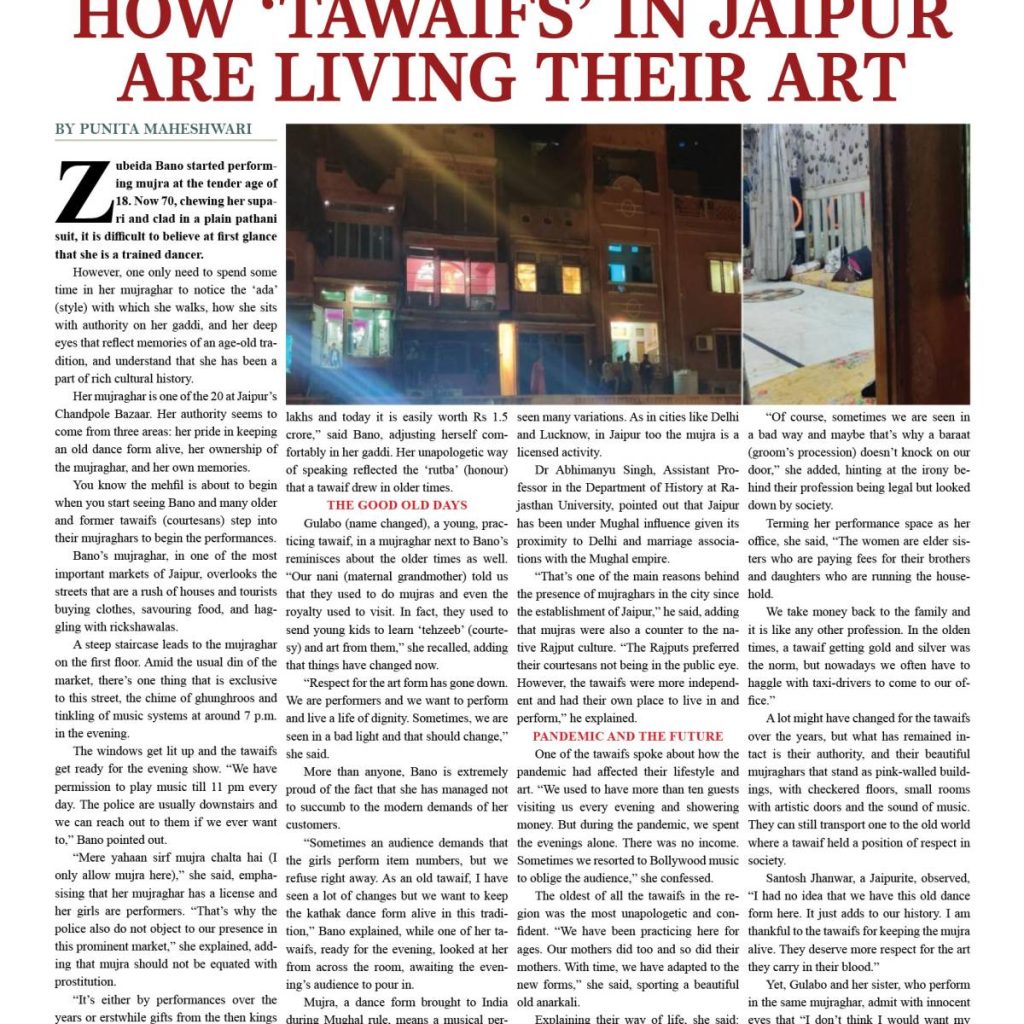

Bano’s mujraghar, in one of the most important markets of Jaipur, overlooks the streets that are a rush of houses and tourists buying clothes, savouring food, and haggling with rickshawalas.

A steep staircase leads to the mujraghar on the first floor. Amid the usual din of the market, there’s one thing that is exclusive to this street, the chime of ghunghroos and tinkling of music systems at around 7 p.m. in the evening.

The windows get lit up and the tawaifs get ready for the evening show. “We have permission to play music till 11 pm every day. The police are usually downstairs and we can reach out to them if we ever want to,” Bano pointed out.

“Mere yahaan sirf mujra chalta hai (I only allow mujra here),” she said, emphasising that her mujraghar has a license and her girls are performers. “That’s why the police also do not object to our presence in this prominent market,” she explained, adding that mujra should not be equated with prostitution.

“It’s either by performances over the years or erstwhile gifts from the then kings that we have earned these mujraghars. I bought this place 10 years ago for Rs 30 lakhs and today it is easily worth Rs 1.5 crore,” said Bano, adjusting herself comfortably in her gaddi. Her unapologetic way of speaking reflected the ‘rutba’ (honour) that a tawaif drew in older times.

The good old days

Gulabo (name changed), a young, practicing tawaif, in a mujraghar next to Bano’s reminisces about the older times as well. “Our nani (maternal grandmother) told us that they used to do mujras and even the royalty used to visit. In fact, they used to send young kids to learn ‘tehzeeb’ (courtesy) and art from them,” she recalled, adding that things have changed now.

“Respect for the art form has gone down. We are performers and we want to perform and live a life of dignity. Sometimes, we are seen in a bad light and that should change,” she said.

More than anyone, Bano is extremely proud of the fact that she has managed not to succumb to the modern demands of her customers.

“Sometimes an audience demands that the girls perform item numbers, but we refuse right away. As an old tawaif, I have seen a lot of changes but we want to keep the kathak dance form alive in this tradition,” Bano explained, while one of her tawaifs, ready for the evening, looked at her from across the room, awaiting the evening’s audience to pour in.

Mujra, a dance form brought to India during Mughal rule, means a musical performance by a dancing-girl and paying of respects. Over the years, the art form has seen many variations. As in cities like Delhi and Lucknow, in Jaipur too the mujra is a licensed activity.

Dr Abhimanyu Singh, Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Rajasthan University, pointed out that Jaipur has been under Mughal influence given its proximity to Delhi and marriage associations with the Mughal empire.

“That’s one of the main reasons behind the presence of mujraghars in the city since the establishment of Jaipur,” he said, adding that mujras were also a counter to the native Rajput culture. “The Rajputs preferred their courtesans not being in the public eye. However, the tawaifs were more independent and had their own place to live in and perform,” he explained.

Pandemic and the future

One of the tawaifs spoke about how the pandemic had affected their lifestyle and art. “We used to have more than ten guests visiting us every evening and showering money. But during the pandemic, we spent the evenings alone. There was no income. Sometimes we resorted to Bollywood music to oblige the audience,” she confessed.

The oldest of all the tawaifs in the region was the most unapologetic and confident. “We have been practicing here for ages. Our mothers did too and so did their mothers. With time, we have adapted to the new forms,” she said, sporting a beautiful old anarkali.

Explaining their way of life, she said: “We are the same as everyone else at home. Why would it be different?”

“Of course, sometimes we are seen in a bad way and maybe that’s why a baraat (groom’s procession) doesn’t knock on our door,” she added, hinting at the irony behind their profession being legal but looked down by society.

Terming her performance space as her office, she said, “The women are elder sisters who are paying fees for their brothers and daughters who are running the household. We take money back to the family and it is like any other profession. In the olden times, a tawaif getting gold and silver was the norm, but nowadays we often have to haggle with taxi-drivers to come to our office.”

A lot might have changed for the tawaifs over the years, but what has remained intact is their authority, and their beautiful mujraghars that stand as pink-walled buildings, with checkered floors, small rooms with artistic doors and the sound of music. They can still transport one to the old world where a tawaif held a position of respect in society.

Santosh Jhanwar, a Jaipurite, observed, “I had no idea that we have this old dance form here. It just adds to our history. I am thankful to the tawaifs for keeping the mujra alive. They deserve more respect for the art they carry in their blood.”

Yet, Gulabo and her sister, who perform in the same mujraghar, admit with innocent eyes that “I don’t think I would want my child to continue this. I would rather have them study.”