Richard Wagner’s influence on Holst was deep and profound which went on to shape his later life. While studying at RCM Holst enlarged his circle of friends with likeminded fellow students such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Ireland amongst others…writes Dilip Roy

I dedicate this piece to my grandson Dhyaan a third generation ROY who has been taking interest in the history and cultures of the world specially those of India.

Gustavus Theodore von Holst (1874-1934) was a British composer born in Gloucestershire, England of German and Swedish origin. He came from the family of musicians who were professional in their respective fields. He studied composition at the London’s Royal College of Music later becoming a teacher at Morley College where he served as a musical director from 1907 until 1924. Holst’s work became popular in the early 20th century, but his international success was instant with the composition pf The Planets which had the echoes of Hindu cosmology and that of Lord Indra God of Thunder.

Richard Wagner’s influence on Holst was deep and profound which went on to shape his later life. While studying at RCM Holst enlarged his circle of friends with likeminded fellow students such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Ireland amongst others. Together they created a very English version of “ continental intellectual café society” by becoming regulars at a tea shop in Kensington where they discussed everything from philosophy to art and literature and enthused about Wagner. Holst’s passion for Wagner became clear when he visited Royal Opera House at Covent Garden in the summer of 1892 because it is here that a 19th century musical giant Gustav Mahler a staunch Wagnerian was making his debut conducting Wagner Tetralogy The Ring Cycle and “Tristan and Isolde.” Mahler was regarded as last of the Austro-German Romantic composer of that period. For Holst Tristan was the greatest revelation with its saturated chromatic yearning for the infinite, which Holst realized was far more impressive than he had imagined than the piano score version he had studied so avidly. The performances were reviewed by none other than Nobel laureate George Bernard Shaw avid Wagnerite himself.

Gustav Holst came across a book called Silent Gods and Sun-Stepped Lands by RW Frazer and discovered stories associated with Hinduism for the first time. Holst’s interest in Indian mythology and philosophy grew deeper as he read the ancient Indian books on Vedas, Upanishads and The Bhagavad Gita. This resulted in the culmination and became musically evident in the opera Sita (1901-06) which occupied nearly seven years of his life and the inspiration came from Wagner’s Ring Cycle. Holst was planning his opera on the epic scale like the Ring but due to financial reasons opera did not get the premiere it deserved. The combined influence of Hindu spiritualism and English folk tunes enabled Holst to go beyond the all-consuming influences of Wagner and forge his own style. Although much of his grand opera Sita is very much a Wagnerian exercise but towards the end a change comes over the music, and the beautifully calm phrases of the hidden chorus representing the Voice of the Earth are in Holst’s own language. Holst was able to decipher the Sanskrit script and translate words with the use of dictionary and eventually he went on to translate as many as twenty invocations to the Hindu pantheon from the Rig Veda and is considered a landmark event in the composer’s development. One example of his clarity may also be found in his translation of the Hymn to Agni, God of Fire.

Whilst in Berlin, Holst worked on a symphonic poem based on a Sanskrit legend Indra follows the eponymous fire, thunder and rain God as he battles with a dragon over parched Indian field. It contains some powerful ideas, but with its Wagnerian echoes the battle might just as well have taken above the Pomeranian plain nearby. Holst’s mind was split between things Indian and German. Holst continued to be inspired by India as he was working on a large scale composition for chorus and orchestra based on a mythological poem Megadutam (The Cloud Messenger) by the great Sanskrit poet the famous Kalidasa. A poet sends a cloud with a message to his beloved. It passes over cities and temples with their various festivities before reaching the women and whispering the message to her in her sleep. This allowed him to compose various set pieces and dances and Holst was greatly satisfied with it. Two Eastern Pictures (1911) provide “a more memorable final impression of Kalidasa.” Holst’s other works included various episodes from the epic Mahabharata.

Post Script: I … believe in the Hindu doctrine of Dharma which is one’s path in life. If one is lucky or maybe (unlucky – it doesn’t matter) to have a clearly appointed path to which comes naturally whereas any other one is an unsuccessful effort, one ought to stick to the former. And I am Oriental enough to believe in doing so without worrying about the “fruits of action” that is success or otherwise. (Gustav Holst)

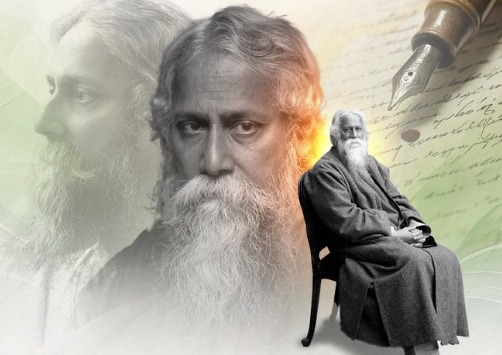

(Dilip Roy is an elected Fellow of Royal Asiatic Society U.K. and an Aficionado of Richard Wagner. Dilip Roy’s other major contribution include a commemorative article on a 19th century musicologist Sir SM Tagore for Royal College of Music London, and was displayed on the occasion of hundred years of Tagore Medal in November 1999 RCM South Kensington.)

ALSO READ- Sun Mark Denies Allegations Against Chairman Lord Rami Ranger