It’s a sub-genre that lends itself well to visual depiction — remember how many of the James Bond films (not the books though) featured submarines, or for that matter, Tintin’s adventures? — but it makes for equally captivating reading…writes Vikas Datta

Take a fairly large number of people together in a comparatively cramped space deep underwater — a domain unfamiliar and fatal for unprotected humans, throw in the brewing tensions whenever disparate humans are in a confined space for a considerable time, and some existing/futuristic technology — these are the basic makings of the “submarine story” — a captivating sub-genre of the always popular maritime fiction adventures.

Though submarines are helpful for exploring the last unmapped space on our planet — the deep sea and its wonders, their primary role is as largely silent, virtually undetectable machines of war. The characteristics of the vessel — its strengths, the vulnerabilities, and the risks, the calibre and capabilities of its operators, and its tasks, can generate many more plot devices.

It’s a sub-genre that lends itself well to visual depiction — remember how many of the James Bond films (not the books though) featured submarines, or for that matter, Tintin’s adventures? — but it makes for equally captivating reading.

Take its primary role. When two submarines face off, it is akin to two blindfolded fighters trying to track each other by only the sound they make. And when other weapon platforms on different domains — surface or aerial — join in to hunt submarines, the tension ratchets up manifold. Imagine knowing you are being targeted, but being unable to see the threat and unlike on land, there is no place to hide beyond a limited space.

Submarine stories are therefore set mostly in wars, or near wars, whether between nations or even one individual fighting his own battle.

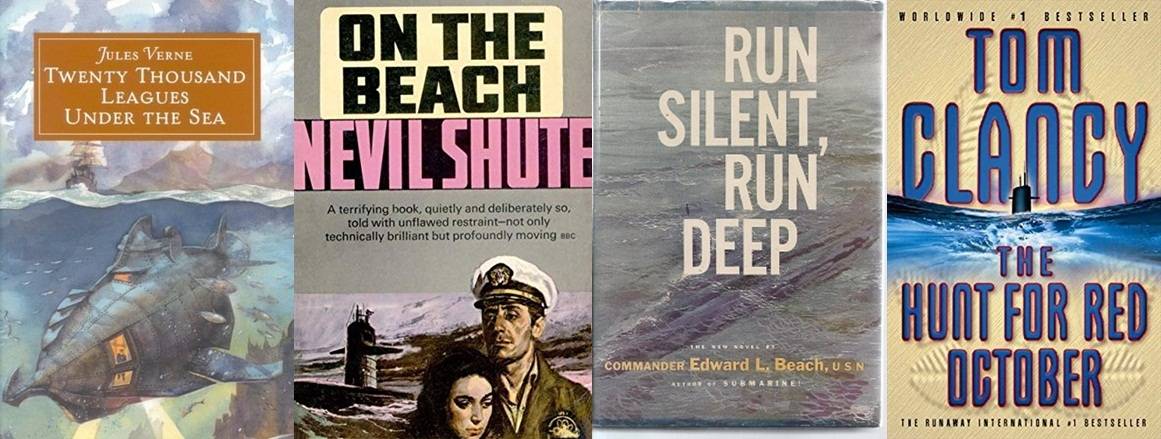

That happens to be the originator of this sub-genre — visionary French science fiction writer Jules Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas” (French 1872; first English translation, 1873). This story is pretty well-known due to all the films it has inspired, but it seems more relevant to know how this work failed to receive its due from the initial English translations.

Not only was the name mistranslated to “sea”, instead of “seas”, denoting the length of the voyages of Captain Nemo’s ‘Nautilus’, not their depth, but the account also suffered from the haste and predilections of these translators.

Verne was not the “inventor” of submarines, which were around in his time, though extremely primitive, but he did forecast pretty accurately their modern versions.

Though some critics initially disputed this, this was due to the first British and American translators, who abridged his works by chopping out most of the science and the longer descriptive passages, committed thousands of basic translating errors, and even censored the texts by removing or diluting anti-British or anti-American references, or rewrote them to suit their personal views. It took more faithful translations — the first in 1962, and onwards — to restore Verne’s credentials.

Submarines crop up across adventure fiction in works ranging from those of Alistair Maclean to Nevil Shute, and from accomplished spy novelists such as Len Deighton, and even romantic comedy writers like Kathy Lette, or practitioners of high fantasy — with a punch, like Terry Pratchett. Let’s look at a few of them.

Denys Rayner’s “The Enemy Below” (1956) is a story of a battle, over four days, between a British destroyer and a German U-Boat in the South Atlantic Ocean, with both commanders gaining increasing respect for each other, till the time they are literally and metaphorically in the same boat. The author, who was a Royal Navy officer during World War II, and had commanded anti-submarine operations, goes on to tell how much of the story is true, or even possible.

“Run Silent, Run Deep” (1955) by Edward L. Beach Jr., who had a respectable career as a US Navy submarine commander, transposes the action to the Pacific theatre. An unmatched guide to this form of warfare, it also goes on to deal with equally important and relevant human aspects of courage, loyalty, honour, ambition, and revenge, and how war tests and amplifies them. The possibility of modern war setting its moral standards is brought out quite shockingly in the denouement.

On the other hand, Shute’s post-apocalyptic “On the Beach” (1957), set in a world where an accidental nuclear exchange has devastated the entire northern hemisphere and a small band of survivors in southern Australia live out their limited lives as the radioactive clouds drift towards them, has a key submarine sub-plot.

With the only survivors being in southernmost parts of Australia, South Africa, and South America, the arrival of a strange radio message from Seattle creates hope, and an American submarine, which had survived since it was in southern waters, sets out to investigate.

On the way, they confirm that the radioactive fallout has not abated, no other life remains, and even their venture was a forlorn hope.

The Cold War offered fertile ground for use of submarines.

Deighton worked them well into the various installments of his story of an unnamed, unglamorous spy that began with “The IPPCRESS File” (1962). “Horse Under Water” (1963), the second installment, deals with retrieving items — which keep on changing from material to ideological to technical, from a German U-boat sunk off the Portuguese coast in the last days of World War II.

Then, “Spy Story” (1974) sees its protagonists, two mid-level intelligence analysts, returning home from a six-week stint on a nuclear submarine in the Arctic, through various stratagems, twists and turn, and mysteries, and then, head back to the Arctic on a submarine where a curious game is to be played.

Maclean’s adventures, often set in bleak places such as the Arctic, frequently draw in submarines, for reaching the wilderness, if not anything else, and then, as a good place for the layered and twisty denouement that marks most of his works. “Ice Station Zebra” (1963) is a sterling example, with what appears to be a simple rescue operation turning out to have more than what meets the eye.

If maritime thriller aficionados have read just one submarine thriller, it’s likely to be Tom Clancy’s debut “Hunt for Red October” (1984), which birthed the techno-thriller genre.

The story of a leading Red Navy officer’s elaborate revenge against a system he has come to personally oppose, it is probably the most realistic account of submarine operations, uses, and policies as the story shifts from multiple submarines, to meetings of the Soviet politburo, at the White House, and in Soviet and US naval headquarters as American authorities devise a plan to get the windfall heading their way.

Submarines, as mentioned, play key roles in at least two Tintin adventures — a positive, but ultimately unfruitful one, in “Red Rackham’s Treasure”, and a little more adverse one in “The Red Sea Sharks”.

Moving on to the more fantastic occurrences, there is a prototype in Terry Pratchett’s “Jingo” (1997), named by its brilliant but sadly unimaginative inventor as “Going-Under-the-Water-Safely Device”. It goes on to play a key role in this stellar installment of the Sam Vimes/City Watch cycle of the Discworld saga which calls out xenophobia, racism, and cultural insularity, while satirising jingoism, extreme nationalism, and Lawrence of Arabia.

And then there is finally “Fantastic Voyage” (1966), which is different from most of the above — insofar as they were books that became films, but this was a film whose novelisation became as famous — or rather, stayed more famous for over four decades than the movie.

The plot is a desperate attempt to cure a defecting scientist, badly wounded in his attempt, by a team of intrepid adventurers from inside his body, via miniaturisation!

As it was Isaac Asimov who adapted the script, the book corrected countless scientific errors, while adding several elements and nuances — such as a character identifying the mole, who is painted more grey than black, while bringing to focus science problems brought by the movie’s premise, say, seeing when wavelengths of visible light are larger than the eyes of the crew, and getting air from the lungs when molecules are not much smaller than the submarine.

There are many more, but these works offer a good start. Dive in!

ALSO READ-‘March’ towards worthy reading