Civil unrest in brewing in Pakistan as fragile forex position leading to fuel import crisis and paucity of goods … writes Dr Sakariya Kareem

Pakistan’s central bank, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has warned its government about dwindling forex reserves and its impact on country’s ability to sustain imports. The decline in SBP’s Forex reserves, which fell to $8.24 billion on June 17 is likely to continue due to pressure of debt servicing and other payments in near future.

To preserve the diminishing Forex, SBP has advocated a temporary ban on import of all non-essential goods. It has apparently highlighted the risk ballooning fuel imports entail for the energy security of the country.

Pakistan’s total petroleum imports stood $9.7 billion during fiscal year 2020-21. But as rising global prices pushed its import bill to more than $14.46 billion in July-April period of the current fiscal year and its Forex position tightened, the ramifications on Pakistan’s oil imports have been critical.

Warning that the rising energy imports are eating into Forex reserves, SBP fears that further erosion could seriously undermine Pakistan’s ability to import fuel. Targeting some decrease in fuel demand, the Pak government has already withdrawn many subsidies on fuel, which resulted in a sharp increase in domestic energy prices. However, it has not been able to bring down the import bill to a comfortable level. According to SBP, the Ministry of Energy & Petroleum should be asked to formulate and implement stringent policy measures to contain demand for energy products.

The rapidly depreciating local currency, i.e. Pakistani Rupee (PKR) is further compounding the problem. Its steady depreciation continues with exchange rate reaching from PKR199/USD on 6th June to PKR 207/US D on 6th July 2022. The situation has turned into a vicious cycle as depreciating currency leads to rise in fuel import bill which makes the fiscal position even weaker. On currency, SBP has recently attempted some large scale interventions in the market. However, its limited capacity to control the exchange rate has yielded only paltry returns.

Low level of Forex reserves has unnerving effect on international fuel suppliers also. Their decline in trust for Pakistan’s import capacity is revealed by a visible decline in acceptance of letters of credit (LC) issued by Pak banks. International banks as the receiving party in the LCs, are asking for a third-party bank for a confirmation; a guarantee that the Pak bank will pay the LC amount when it falls due. According to a banking professional quoted in Pakistani media, foreign banks are cautious dealing with local counterparts right now keeping in mind the position of the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

As a result, the recent tender auction by state-owned Pakistan State Oil (PSO) attracted pricier offers from suppliers which subsequently mean higher oil prices in the country. Moreover, most of PSO’s suppliers remained reluctant with only one supplier Idemitsu responding to its tender for supply of 54000 MTs of gasoline in July 2022. Bigger international players are either choosing to wait until the economic situation improves, or putting up bids at higher premiums to stay in the market.

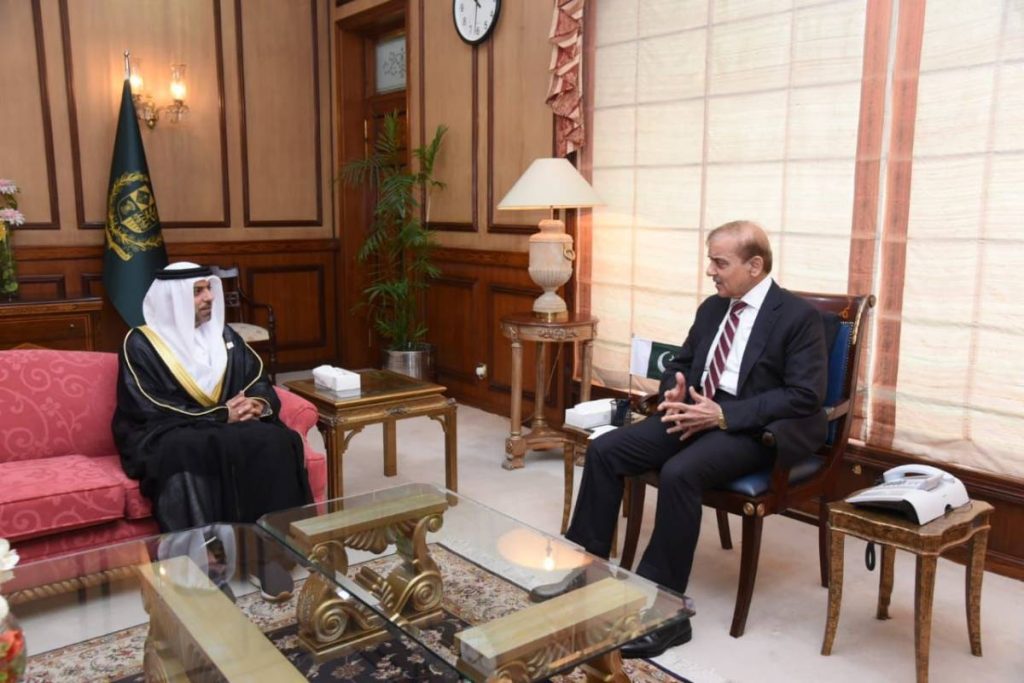

Of late, Islamabad has relied heavily upon bilateral fuel import agreements on deferred payment basis with major gulf countries, i.e. Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates (UAE). Recently, the country was successful in securing resumption of a Saudi facility for providing oil on deferred payment. However, its monthly limit of $100 million is insufficient to provide a meaningful relief for the Forex reserves.

Meanwhile, Pak Finance Ministry is also predicting a gloomy picture for the economy and BoP position. It reportedly assessed that “the underlying macroeconomic imbalances associated with domestic and international risks are making growth outlook indistinct,” and that SBP’s demand management policy was unlikely to be successful in the face of supply side constraints and higher international commodity prices that may further erode the income levels.

Perceptions of a higher country risk have been further fuelled by the downgrades by global ratings agencies. Recently, Moody’s revised down Pakistan’s rating from stable to negative, rising credit default spreads for the country. So far, pressure from IMF has forced Islamabad to introduce some reforms in the energy market like fuel subsidy reduction and power tariff increase. However, in absence of any structural reforms, the country’s fiscal fate hangs majorly on two factors only: the generosity of its lenders and the movement of international crude prices.