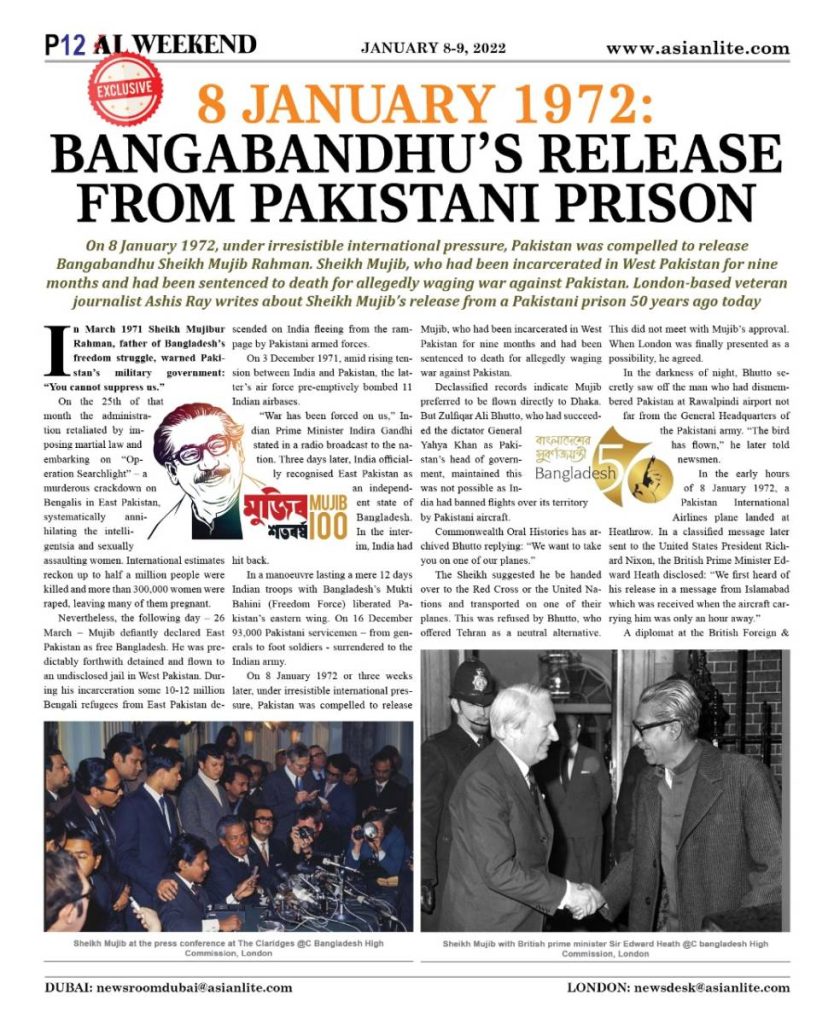

On 8 January 1972, under irresistible international pressure, Pakistan was compelled to release Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Rahman. Sheikh Mujib, who had been incarcerated in West Pakistan for nine months and had been sentenced to death for allegedly waging war against Pakistan. London-based veteran journalist Ashis Ray writes about Sheikh Mujib’s release from a Pakistani prison 50 years ago today

In March 1971 Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, father of Bangladesh’s freedom struggle, warned Pakistan’s military government: “You cannot suppress us.”

On the 25th of that month the administration retaliated by imposing martial law and embarking on “Operation Searchlight” – a murderous crackdown on Bengalis in East Pakistan, systematically annihilating the intelligentsia and sexually assaulting women. International estimates reckon up to half a million people were killed and more than 300,000 women were raped, leaving many of them pregnant.

Nevertheless, the following day – 26 March – Mujib defiantly declared East Pakistan as free Bangladesh. He was predictably forthwith detained and flown to an undisclosed jail in West Pakistan. During his incarceration some 10-12 million Bengali refugees from East Pakistan descended on India fleeing from the rampage by Pakistani armed forces.

On 3 December 1971, amid rising tension between India and Pakistan, the latter’s air force pre-emptively bombed 11 Indian airbases.

“War has been forced on us,” Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi stated in a radio broadcast to the nation. Three days later, India officially recognised East Pakistan as an independent state of Bangladesh. In the interim, India had hit back.

In a manoeuvre lasting a mere 12 days Indian troops with Bangladesh’s Mukti Bahini (Freedom Force) liberated Pakistan’s eastern wing. On 16 December 93,000 Pakistani servicemen – from generals to foot soldiers – surrendered to the Indian army.

SASHANKA BANERJEE: “After about an hour of small talk, ‘Bongo Bondhu’ stood up and started singing ‘Aamar Shonaar Bangla, Aami Tomaye Bhalobashi’ (Oh my golden Bengal, I love you dearly)

On 8 January 1972 or three weeks later, under irresistible international pressure, Pakistan was compelled to release Mujib, who had been incarcerated in West Pakistan for nine months and had been sentenced to death for allegedly waging war against Pakistan.

Declassified records indicate Mujib preferred to be flown directly to Dhaka. But Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who had succeeded the dictator General Yahya Khan as Pakistan’s head of government, maintained this was not possible as India had banned flights over its territory by Pakistani aircraft.

Commonwealth Oral Histories has archived Bhutto replying: “We want to take you on one of our planes.”

The Sheikh suggested he be handed over to the Red Cross or the United Nations and transported on one of their planes. This was refused by Bhutto, who offered Tehran as a neutral alternative. This did not meet with Mujib’s approval. When London was finally presented as a possibility, he agreed.

ALSO READ: Growing calls to create separate ministry for minorities in Bangladesh

In the darkness of night, Bhutto secretly saw off the man who had dismembered Pakistan at Rawalpindi airport not far from the General Headquarters of the Pakistani army. “The bird has flown,” he later told newsmen.

In the early hours of 8 January 1972, a Pakistan International Airlines plane landed at Heathrow. In a classified message later sent to the United States President Richard Nixon, the British Prime Minister Edward Heath disclosed: “We first heard of his release in a message from Islamabad which was received when the aircraft carrying him was only an hour away.”

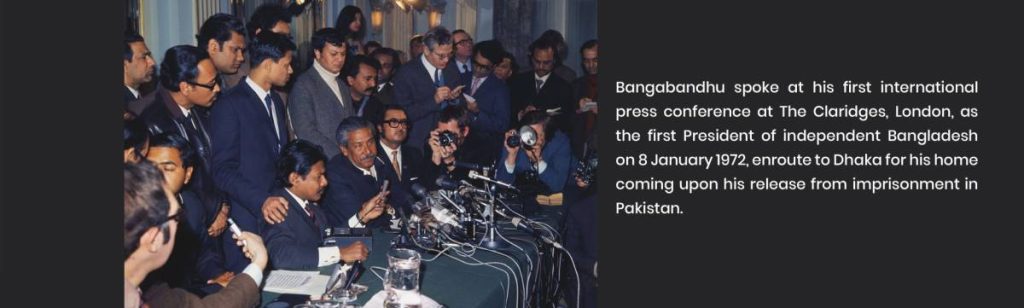

A diplomat at the British Foreign & Commonwealth Office was rushed to receive him and escort him to Claridge’s Hotel in London’s Mayfair, where de facto representatives of Bangladesh in the British capital had hurriedly booked a suite.

Heath was holidaying in the country. He now quickly returned to his official residence-cum-office at 10 Downing Street to meet Sheikh Mujib. The talks lasted about an hour.

The Sheikh asked Britain to recognise Bangladesh. Following this, Heath told the House of Commons: “We would do our utmost to help Bangladesh in the present situation.” Less than a month later, the United Kingdom announced establishment of full diplomatic relations with Dhaka.

Mujib also requested Heath to persuade the US – which had nakedly supported Khan’s junta in their brutal repression of in East Pakistan – to acknowledge Bangladesh as a sovereign nation.

Heath argued before Nixon: “If we delay too long, the Communist countries will get a start on us.” America duly fell in line in the spring of 1972.

At a packed press conference at Claridge’s, the Sheikh memorably declared a free Bengali country was “an unchallengeable reality”.

The New York Times reported he said at this interaction he had been held in a condemned cell. It quoted him as opening his remarks by saying: “Gentlemen of the press, today I am free to share the unbounded joy of freedom with my fellow countrymen. We have earned our freedom in an epic liberation struggle.” The paper further described: “He spoke bitterly of what the Yahya Khan regime had done in East Bengal”, quoting him as saying, ‘they tortured boys and girls’, ‘mercilessly’ killed people, and burned ‘hundreds of thousands of buildings’. Reproducing his remarks verbatim, it added that he further stated: “I think if Hitler had been alive today, even he would have been ashamed.”

Heath shared with Nixon: “He (Mujib) was anxious to reach Dacca as soon as possible and we gave him an RAF aircraft for the onward journey.” Mrs Gandhi had arranged an Air India plane for the purpose, but now agreed with Heath that the British jet would stop in Delhi en route to Dhaka. The Sheikh heartily endorsed this.

London-based Indian diplomat Sashanka Banerjee, who was deputed to accompany Mujib as an Indian officer on special duty, depicted: “After about an hour of small talk, ‘Bongo Bondhu’ stood up and started singing ‘Aamar Shonaar Bangla, Aami Tomaye Bhalobashi’ (Oh my golden Bengal, I love you dearly). I was seated next to him, and as he started singing, I too stood up as he did. Mujibur Rahman asked me to join him in singing the song with him, which I did.”

ALSO READ: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman@100

He went on: “At the end, he turned towards me and asked what I thought of the song. I had understood that Mujib wanted the song to be the national anthem or ‘jaatiyo shongeet’ of Bangladesh. Who could deny that it was a beautiful song fit to be the Jaatiyo Songeet of Bangladesh. ‘You are right,’ he said, ‘that was what I was thinking too. Good then, that will be the song that will be the national anthem of Bangladesh’.”

The Royal Air Force Comet refuelled at its bases in Cyprus and Oman before landing in Delhi on the morning of 10 January to a rapturous reception by the Indian cabinet. As Mujib rested before formal discussion with Mrs Gandhi, Banerjee informed her the Sheikh desired, withdrawal of Indian forces from Bangladesh be advanced to 31 March from 30 June. She, according to Banerjee, asked him to communicate back to him that this be formally mentioned at the ensuing meeting. This Mujib did; Indira immediately accepted the request.

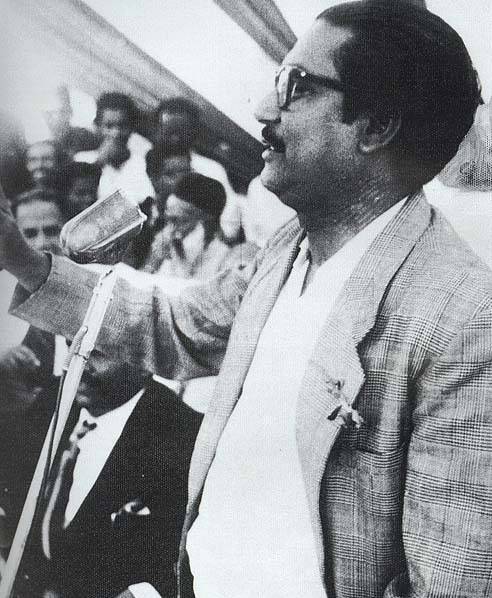

A few hours later, Sheikh Mujib arrived in Dhaka to a tumultuous welcome. Banerjee’s eye-witness account portrayed: “Over a million people had gathered to receive the Bangladesh leader at the Romna Maidan, echoing slogans of ‘Joy Bongo Bondhu, Joy Bangla’. Raising his very masculine voice, Bongo Bandhu (friend of Bengal) declared standing on the podium: ‘My countrymen, rejoice. Bangladesh is now a sovereign, independent nation.”

It was a heady moment for he world at large, unforgettable even after half a century.