For the first time, the USA is facing the strategic challenge of two nuclear-armed peer competitors. Washington DC is in a unique position with two potential adversaries, since Russia and China are on friendly terms with each other….reports Asian Lite News

China possesses one of the most impressive missile inventories in the world, ranging from cruise missiles all the way up to nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM).

Indeed, the US intelligence community has described China’s ballistic and cruise missile development programs as “the most active and diverse … in the world”. According to the Pentagon, China launched approximately 135 ballistic missiles in 2021 for training and testing purposes. “This was more than the rest of the world combined, excluding ballistic missile employment in conflict zones.” The number launched in 2022 is unlikely to be fewer, especially once its furious antics against Taiwan after the American politician Nancy Pelosi’s visit are taken into consideration.

For the first time, the USA is facing the strategic challenge of two nuclear-armed peer competitors. Washington DC is in a unique position with two potential adversaries, since Russia and China are on friendly terms with each other.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is investing heavily in nuclear forces, and efforts “exceed previous modernization attempts in both scale and complexity,” according to the Pentagon. Its nuclear triad encompasses land-, sea- and air-based delivery.

In a recent report entitled Missile Technology: Accelerating Challenges, the UK-based International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS) stated: “…China is pursuing what is by all accounts the most substantial shift in its nuclear posture in decades.”

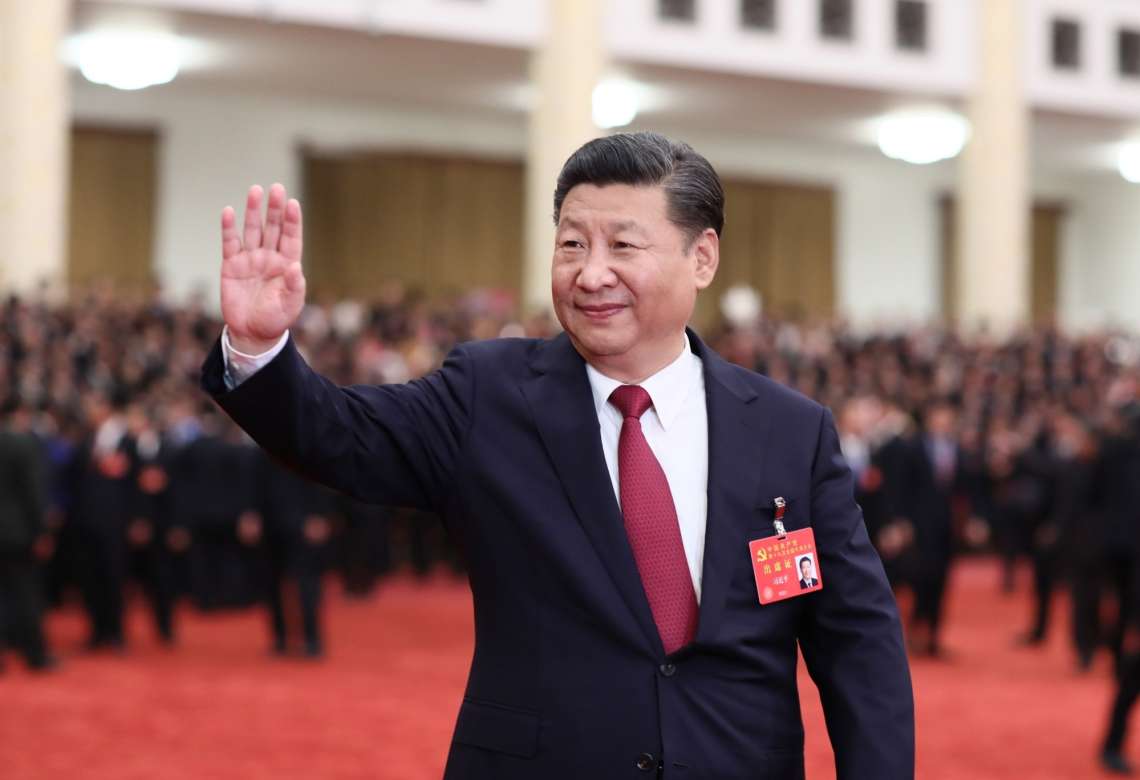

Quite apart from the national prestige that nuclear weapons bring to Chairman Xi Jinping, the country’s massive investment includes the pursuit of “a larger and increasingly capable nuclear missile force that is more survivable, more diverse and on higher alert than in the past, including nuclear missile systems designed to manage regional escalation and ensure an intercontinental second-strike capability”.

Beijing’s nuclear weapon stockpile exceeds 400 operational warheads, according to the US Department of Defense (DoD) estimates. By the time it reaches its basic modernization target of 2035, the PLA Rocket Force (PLARF) will own approximately 1,500 warheads.

This is intensely problematic, for China has never explained the growth in its nuclear forces, apart from vague descriptions from the likes of Xi speaking of “accelerating the construction of advanced strategic deterrent” capabilities.

The IISS affirmed, “…In general terms, there is no unified, authoritative explanation for the ongoing nuclear force expansion, and debates as to the cause or causes of this remain unresolved.”

A belligerent state quadrupling its nuclear arsenal within a dozen years is intensely worrying. This is even more so when that country refuses to acknowledge its startling nuclear buildup.

The deterioration in Sino-US relations accelerated in 2017, and this presumably is an important part of China’s calculus to boost its nuclear forces. The IISS report speculated: “Chinese leaders may have started to perceive a heightened probability of general conflict with the US, and may thus calculate that a more robust nuclear deterrent may be necessary to induce caution in the US and in the way it may choose to escalate. In particular, as the conventional balance of power in the Indo-Pacific, particularly within the Second Island Chain, shifts in China’s favour, Beijing may fear that the US would contemplate offsetting this inferiority with resort either to the actual first use of nuclear weapons or to threats of nuclear first use to coercive ends.”

Then again, the IISS report suggested that defensive logic could also be playing a part.

“For instance, given China’s continuing assertion of a No First Use policy and traditional emphasis on assured retaliation, a larger nuclear force – one less impervious to both conventional and nuclear counterforce attack – could discourage a turn towards contemplating first use. Similarly, contrary to some existing assessments, a larger Chinese nuclear force could actually dissuade the pursuit of a launch-on-warning posture, which is traditionally associated with states that perceive vulnerability at the strategic level.”

China’s historic posture has been one of “effective counterattack” or “counterattack in self defense”. Yet, because of the current total lack of transparency in China’s nuclear forces, some see a far more nefarious intention. If China decided to attack Taiwan, for instance, a beefy nuclear force could help deter intervention by the USA and its allies.

It is going to take China time to boost its nuclear weapon inventory, especially since it needs to create fissile material. Nonetheless, the USA has already observed that Beijing is increasing its capacity to produce and separate plutonium by constructing fast-breeder reactors and reprocessing facilities.

China maintains that its nuclear forces are kept in a “state of moderate readiness” in peacetime, and would only raise alert levels in a crisis. Yet some analysts are convinced that China is adopting a launch-on-warning posture, which would give Chinese commanders the ability to launch a retaliatory nuclear strike based on the detection of an incoming attack.

Since 2017, the PLARF has been conducting exercises involving such a posture. There is a small chance that launch-on-warning is an interim measure until Beijing possesses what it deems is a sufficiently robust assured-retaliation capability. The IISS believes a shift towards launch-on-warning “remains indeterminate”, though it is perhaps becoming more likely as China operationalizes new silo fields.

Referring to the latter, the US DoD noted in a report late last year that China continues to develop three enormous fields of silo-based missiles, and that “these will cumulatively contain at least 300 new ICBM silos”.

These new silos will probably contain DF-31A ICBMs, although DF-41s could appear in the future too. The silo fields are sited near Yumen, Hanggin Banner and Hami, all deep in northwest China. Yet China has never officially acknowledged them, despite there being absolutely no doubt as to their function.

Interestingly, silo fields mark a departure from China’s recent emphasis on road-mobile launchers. The diversification of launch systems and basing modes, especially these new silo fields plus air-launched ballistic missiles, could indicate technological hedging by China. Overreliance on mobile launchers may be viewed as a vulnerability by the PLARF, so it could be keen to diversify its inventory of launch platforms.

The PLARF possesses conventional short-range ballistic missiles (the DF-15 with a 725-850km range; DF-16 with a 700+km range); medium-range ballistic missiles (the DF-21 with a 1,500km range; DF-17 with a hypersonic glide vehicle); and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (DF-26 with a 3,000km range).

China is estimated to have more than 900 medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles, along with 450 launchers. This includes a dramatic expansion of DF-26 numbers. The DF-26 is capable of hitting ships at sea, plus its conventional warhead can be replaced with a nuclear one.

Also available to the PLA are CJ-10 ground-launched cruise missiles with a 1,500km range, DF-100 ground-launched missiles with a 2,000km range, and DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missiles. The latter is designed to hit naval assets like aircraft carriers.

The DF-17 hypersonic missile was first deployed in 2020, and it will probably replace some short-range ballistic missiles. Based on Chinese writings, the DF-17 is designed to hit foreign military bases and naval assets in the Western Pacific. The USA also believes the DF-17 can carry a nuclear warhead.

China is definitely ahead of the USA in operationalizing hypersonic glide vehicles. Such weapons bring benefits: they quickly reach targets and are difficult to intercept. Their maneuverability increases the chance that they can penetrate enemy air defenses, whilst their non-ballistic trajectory differentiates them from a nuclear attack.

Yet hypersonic glide vehicles carry inherent drawbacks too. Because they require especially developed materials to handle extremely high temperatures, this increases their cost, and limits how many can be produced. Furthermore, small production numbers in turn drive up the unit cost.

On 27 July 2021, China conducted its first-ever fractional orbital launch of an ICBM with a hypersonic glide vehicle. Flying more than 40,000km around the world in just over 100 minutes, this was the longest-ever test of any land attack weapon in the world. The Pentagon assessed that it did not strike its target, although it did come close.

China is expected to angle towards deploying long-range hypersonic glide vehicles on ballistic missile boosters. Their attraction is the ability to evade American midcourse exo-atmospheric missile defense systems. China is afraid that such defenses reduce its second-strike capability in case a war breaks out.

The PLARF’s ICBM inventory comprises the 5,500km-range DF-4 (although it may be operationally phased out by now), the 12,000km-range silo-based DF-5A, and the silo-based DF-5B with five multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRV). With an 11,000+km range, the road-mobile DF-31A can reach most parts of the continental USA, while the modernized DF-31AG, and longer-range DF-41 with MIRVs, were unveiled in 2019.

The DF-5A likely carries a 5-megaton warhead, which would make it the largest-yield weapon in the PLARF arsenal. A follow-on DF-5C and DF-31B could be in development, the US DoD thinks. A long-range DF-27 with a range anywhere between 5,000km and 8,000km is also thought to be in development.

Alternative basing for the DF-41 is being considered, including from railcars and, as already mentioned, silos. Apart from regular trains, high-speed rail – moving at velocities of up to 350km/h – is apparently being considered for its potential for nuclear-tipped missiles. Although an ICBM could fit inside a carriage, its weight would be double or quadruple that of a regular high-speed train’s maximum payload. Such technical challenges would have to be overcome first.

The PLA Navy (PLAN) constitutes an important leg of China’s nuclear triad too. In November 2022, Admiral Sam Paparo, head of the US Pacific Fleet, declared that a new type of submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) had been fielded. Paparo said the PLAN’s six Type 094 Jin-class submarines were now “equipped with JL-3 intercontinental ballistic missiles”. Each submarine can carry 12 missiles. Jin-class vessels have hitherto been armed with JL-2 SLBMs. However, the JL-3 brings new capabilities, including its likely carriage of MIRVs. The incumbent JL-2 has a range of 7,200km, whereas the JL-3 has an estimated range of more than 10,000km.

It was originally thought the JL-3 would only appear in conjunction with the future Type 096 submarine and it is extremely unlikely that sufficient JL-3s have been produced to outfit every Type 094.

In March 2022, Admiral Charles Richard, head of the US Strategic Command warned that the JL-3 would permit China to target the US mainland “from a protected bastion within the South China Sea”. The Jin-class is not a quiet submarine, meaning they can be more easily tracked by hostile forces. This limits their usefulness in waters far from China, as they are relatively vulnerable.

The third leg of the triad is the PLA Air Force (PLAAF). After decades sitting on the sidelines, the PLAAF is now receiving a more prominent nuclear role. In 2018, the Pentagon declared that the PLAAF had been reassigned a nuclear mission. This is via the CH-AS-X-13 air-launched ballistic missile carried by H-6N bomber aircraft, which can be refuelled in the air to give it a great range.

No country has ever fielded a nuclear-capable air-launched ballistic missile before, so China seems set to be the first when this missile type is fully fielded in perhaps the mid-2020s.

China is expanding its inventory of conventional, dual-capable and nuclear missiles without any formal arms constraints. Whereas Russia and the USA have limited themselves with mutual agreements such as the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, China has progressively grown a large inventory of deadly missiles.

Chinese officials viewed America’s withdrawal from the INF Treaty in August 2019 as a negative development. Even though the PLA hugely overmatches the USA in INF classes of missiles, China will be concerned about the future appearance of new types of American missiles and an overall more uncertain strategic environment.

For example, new American missiles appearing near the Second Island China – for example, on Guam- could blunt PLA military projection power near its shores. Nor can the USA field more than 700 ICBMs, short-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers, amounting to 1,550 warheads, under its bilateral Russia-US New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. This New START agreement will expire in 2026.

However, China is adamant that it will not participate in any trilateral arms control agreement with Russia and the USA. It refuses to voluntarily allow controls to be put on its nuclear arsenal, underscoring its paranoia and secrecy.

China’s recent snowballing of its nuclear inventory can be described as a “strategic breakout”. Dangerously, it could result in an even more coercive nuclear policy from China – as if its current behavior with conventional weapons were not bad enough. (ANI)