A major problem with these projects in Africa is the excessive presence of Chinese stakeholders. The majority of these projects in African countries like Ghana, Uganda, and Mozambique, to name a few, are being funded by Chinese financial institutions. Other than Chinese banks, the Chinese element is present excessively, manifesting as Chinese construction companies who are undertaking projects in the continent. Dr Aditi Sharma writes on the perils of the Chinese Model of resource-backed infrastructure financing in Africa

The model of resource-backed lending for infrastructure development has gained renewed attention in the development financing discourse as well as international media controversies. The model has attracted attention for two reasons: one, the nature of the resources involved, and second, the controversial nature of the lenders involved, namely China. Moreover, the borrowers involved in the process are also often poor developing countries, prone to unfair debt deals, further exacerbating the international community’s concerns.

To be succinct, the resource-financed infrastructure exchange takes place in two ways. In one case, the income from resource sales is used for repaying the loans to the lending nations, and in the other case, the natural resources are swapped in the future in return for the provision of infrastructure. Though the model of financing appears pro-development and efficient for Africa, as evident, the exact execution of the project may not be so.

A major problem with these projects in Africa is the excessive presence of Chinese stakeholders. The majority of these projects in African countries like Ghana, Uganda, and Mozambique, to name a few, are being funded by Chinese financial institutions. Other than Chinese banks, the Chinese element is present excessively, manifesting as Chinese construction companies who are undertaking projects in the continent.

Across African nations, there is an outstanding concern amongst the local people as well as companies regarding the effectiveness of infrastructure-related Chinese development aids. The general outcomes of the infrastructure projects are technology transfer from the technology-rich nation. However, there is a very limited technology transfer in this case as there is no focus on capacity building, and the local population is barely involved in projects. The Chinese companies are majorly responsible for infrastructure development in these countries. The process is so Chinese that the labour involved in the construction is also from China. This leads to a gap in the labour market, with locals bereft of employment opportunities. Traditionally, undertaking massive projects solves two major economic issues in the process. First, it helps build public infrastructure and enhance welfare by improving living standards. Second, these projects are undertaken by the governments as a fiscal instrument to increase spending in the economy, generate employment, and curb poverty. Now, with Chinese involvement, huge infrastructure projects are being executed with limited involvement of the locals, rendering the dire issues of poverty and unemployment in these regions unaddressed. This process is far from building self-reliance and long-term sustainability in these nations.

There are other incentive-related issues with this financing model. As long as the borrowing economies are working fine, the model works. However, the moment they default or commodity prices crash, the borrowing nations are in deep trouble. If the collateral (which is the resource they have sworn to swap) loses its value due to market volatility, the borrowers fall short of collateral and default. Countries like Angola and Ghana have faced similar issues. Given the recent default and IMF’s debt restructuring in Ghana, the concern about Chinese loans became crucial. Ghana, using a resource-backed borrowing approach, has collateralized its debt using bauxite, cocoa, and oil. Given its default, if China decides to call off its loans, Ghana stands to lose its natural resources. As per a Ghanaian official, if they are not able to furnish the desired quantities of aluminum from the bauxite ore, the Chinese will ask for other sources of revenue, like tax revenue. The loan agreement empowers China to take over Ghana’s oil, cocoa, bauxite, and even electricity sales earnings to pay off the debt.

Skeptics conjecture that default is often desirable for lending nations as it allows them to act more extractive and stringently. There is another concern with the Chinese presence in Ghana. The mineral extraction has put forest ecosystem in some regions of Ghana in extreme danger, while Chinese authorities have never been known for any kind of environmental considerations.

China’s infrastructure aid is also extending to fund the construction of schools and universities. Experts fear that allows China to exercise its influence in their curriculum by providing it’s flair of ‘Chinese elements.’

A deeper understanding of Chinese presence in Africa allows one to draw parallels to the expansion of imperial and colonial interests in the past. Ideally, lenders providing development aid need not bring their own companies and people to undertake construction in the borrowing nation. After all, the idea is to ensure that developing countries gain technological advancements and capacity. The Chinese way is different and appears decapitating for African sovereignty.

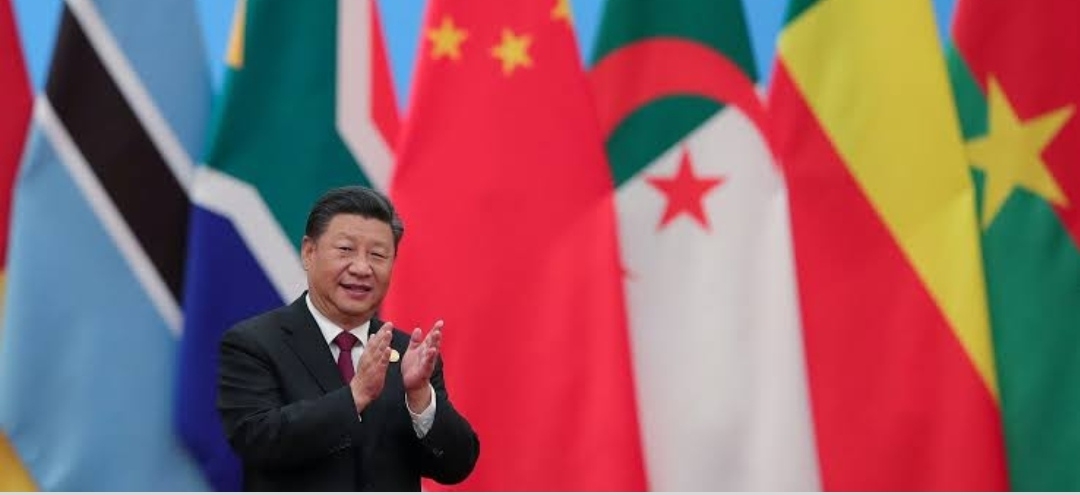

The issue is two-fold, but at the heart of it is one problem: the incentive problem. African governments often lack discipline, end up making extravagant election promises like Ghana did, and do not have the capacity to ensure equitable distribution of outcomes of development projects yet. Given ubiquitous underdevelopment and often recurring political instability, they lack incentives. At the same time, China has excesses incentive but is perverse. Its goals are to eliminate the Western influence, gain strongholds in Africa, discourage democracy promotion and transparency, and gain support, along with the goals of resource capture. That is why Chinese investors do not include any welfare-oriented goals as a pre-requisite condition before making investments, which is a general practice.

Thus, is resource-financed infrastructure essentially a bad model? Theoretically, no, practically may be. As mentioned, it depends on the entities involved and their motivations. We live in a complex geopolitical world where development-oriented economic motives are highly intertwined with other major political motives. Arm-twisting exists. The concerns about the model are related to ownership, sustainability, and disposability of natural resources. The exchange of resources has always existed through trade and has been economically fairer than the current regime of making resources a part of the debt-related vulnerabilities. There are higher chances that the lender can raise the cost of borrowing, not just financially, but also politically. Poor borrowing countries, dependent on China’s debt-restructuring terms, may have to pay the price by relinquishing their resources, sovereignty, political independence, and their voice in international platforms. While the poor in developing countries are not getting any tangible benefits, the flair of neo-imperialism is spreading across Africa.

ALSO READ: South Africa’s Support For Palestinian Cause