More than a half century after 1971 and close to Kissinger’s 100th birthday, the puzzle of why the US administration remained blind to the widening tragedy in East Bengal remains. The Blood reports apart, the sympathy evinced by the American people for Bangladesh failed to persuade Kissinger and the President to change course, writes Syed Badrul Ahsan

Towards the end of this month, Henry Kissinger will become a centenarian. That he will be a hundred years old is surprising. Even more surprising is the fact that despite his frail health he remains mentally alert. In these past couple of years, he has authored a book on leadership and has co-authored another on Artificial Intelligence.

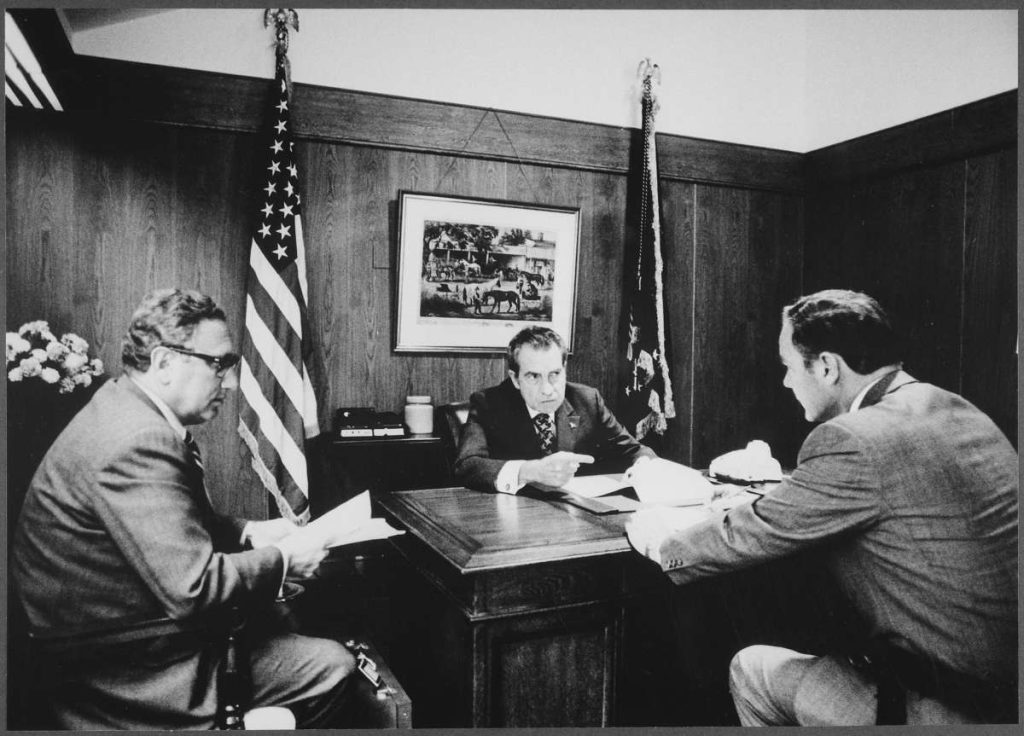

In South Asia, Kissinger’s reputation remains in question, given the controversial role he played in relation to the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971. Every conversation in Bangladesh and India, though not necessarily in Pakistan, revolves around what is regarded as the dark manner in which he, along with President Richard Nixon, promoted the infamous pro-Pakistan tilt even as millions of Bengalis in what was then Pakistan’s eastern province were being subjected to a genocide by the Pakistan army.

Kissinger will likely term the entire episode — of American policy in South Asia in 1971 — as part of Washington’s emphasis on pragmatic foreign policy considerations by the Nixon administration. He has never been on record and neither has Nixon (as long as he lived) with any condemnation of the Yahya Khan junta’s repressive measures in occupied Bangladesh.

The focus of the Nixon-Kissinger policy was an opening to China, with Pakistan as a conduit in July of the year. There was no way the American administration would therefore have Yahya Khan acknowledge the tragedy his soldiers were wreaking in Bangladesh.

In Bangladesh, every conversation around Kissinger inevitably and naturally zeroes in on the insensitivity he demonstrated toward the conscience-driven US diplomat in Dhaka, Archer K. Blood, whose cables to Washington to the effect that the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army needed to be condemned by the administration were callously ignored.

the formulation of US foreign policy on their watch. Kissinger knew what was happening in Dhaka and elsewhere in the occupied country, but he chose to turn his back on it. What was of critical importance to him and to his President was that need to reach out to Mao’s China.

And how do Indians recall Kissinger’s role in 1971? Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon, at the time, were shockingly liberal in the expletives they employed in references to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. As revealed in the records subsequently released, the two men were unable or clearly unwilling to comprehend Mrs. Gandhi’s policy of supporting the Bengalis in their struggle for liberation.

Even on the eve of the Indian leader’s visit to Washington in late 1971, part of the trip she was making to the West to draw attention to the Pakistan military’s atrocities in Bangladesh, the two men happily engaged in a mutual exchange of vituperative comments on Mrs. Gandhi. They met the Indian leader at the White House and once the meeting was over they resumed their tirade against her.

More than a half century after 1971 and close to Kissinger’s 100th birthday, the puzzle of why the US administration remained blind to the widening tragedy in East Bengal remains. The Blood reports apart, the sympathy evinced by the American people for Bangladesh failed to persuade Kissinger and the President to change course. Ignored too were Senator Edward Kennedy’s public denunciations of the military action in Bangladesh.

Indeed, it was not until Indian intelligence revealed the secret contacts between American diplomats in Calcutta and the Bangladesh government’s Foreign Minister Khondokar Moshtaque Ahmed on a repudiation of the liberation struggle and for a solution within an undivided Pakistan in New York on the latter’s part, which exposed the Kissinger hand at work once again. Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmad’s move to prevent Moshtaque from flying to New York put paid to the plan.

And in Pakistan? If Kissinger convinced the Pakistani junta in 1971 that he and the government he was part of would do nothing which could be seen as interference in the actions of the Pakistan army in occupied Bangladesh, by the mid-1970s the National Security Advisor-cum-Secretary of State had earned the ire of the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto government around the issue of Pakistan’s fledgling nuclear policy.

Addressing a public rally in 1976, Bhutto dramatically waved a piece of paper before his audience, claiming it was a letter from Henry Kissinger threatening to make a horrible example of him should he go ahead with the nuclear programme. By mid-1977, Bhutto had been overthrown by the army.

Post-1971, Henry Kissinger would meet Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in New York, where the Bangladesh leader had travelled to attend the UN General Assembly session. A few days later, he made a whirlwind trip to Dhaka, where he was welcomed by Bangabandhu and Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain. In Delhi, Kissinger met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

In subsequent times, out of office with the election of Jimmy Carter as President of the United States in 1976, Kissinger moved into the lecture circuit and writing and travelling. In September 1999, handing over the Felix Houphouet-Boigny Peace Prize on behalf of UNESCO to Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, he had this to say:

‘For me, it is also a special privilege to give this award because Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is somebody whose family I have known for many decades . . . I had the honour of meeting former President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the first President of Bangladesh, shortly after he took office.’

Place this statement in juxtaposition with Kissinger’s role in 1971 and the critical writing on him by Christopher Hitchens in his revealing work, The Trial of Henry Kissinger. Draw your own conclusions.

Move on to December 2016. In an interview with The Atlantic, Kissinger dissembles on Bangladesh with Jeffrey Goldberg:

‘After the opening to China via Pakistan, America engaged in increasingly urging Pakistan to grant autonomy to Bangladesh. In November, the Pakistani president agreed with Nixon to grant independence the following March.’

It was an improbable statement, made years after both Nixon and Yahya had gone to their graves. To suppose that Yahya Khan would grant independence to Bangladesh in March 1972, when his soldiers were engaged in committing genocide in Bangladesh, is preposterous.

That Nixon and Kissinger were busy putting pressure on the junta to agree to Bengali independence flies in the face of everything that went on in 1971.

In 2023, as Henry Kissinger turns 100, people inhabiting the Indian subcontinent will certainly travel back to the diplomacy or the lack of it which marked his understanding of the struggle for Bangladesh in 1971.

(India Narrative)