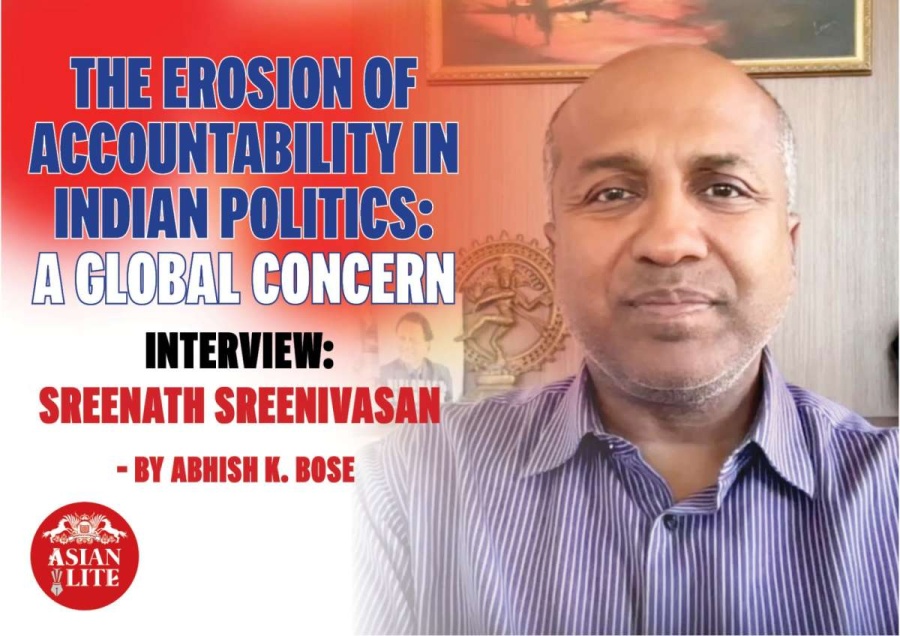

Sreenath Sreenivasan is an expert and scholar in digital communications based in New York city. He is CEO and co – founder of Digimentors. He has also served as the Chief Digital Officer of New York City. He also served as a Professor at the Columbia University graduate school of journalism from 1993 – 2013. In an interview with Abhish K. Bose he discusses India’s descent into a post truth era, the decadence in Indian politics and other related issues.

Excerpts from the interview:

Abhish K. Bose: What are the underlying drivers and consequences of India’s descent into a ‘post-truth’ era, characterised by widespread fact-denial and reality distortion in politics and media, and how specifically has the corporate culture and proliferation of social media platforms since the late 1990s and 2000s contributed to this phenomenon, undermining the foundational principle of ‘facts are sacred, comments are free?”

This is something that we are seeing not just as an India problem, but a global problem. In the United States, we saw the election results. We’re a direct result of the number of lies and misinformation, disinformation, that were directed at American voters. And one of the things we have learned through history is that the more you can convince people that some things are lies, but are not lies, they think that some things are lies, the more they are going to believe everything is a lie.

Everything is not accounted for. Not everything is real. And that’s something that we have to change. If you don’t change it, it means that we’re going to see tremendous damage continue to be done in India and around the world. A lot of this has to do directly with social media and the advent of the internet and WhatsApp in particular. There are so many things that are in fact, uh, become more plausible and possible because of WhatsApp. Good things, but also bad things. And the good things are instant communication, uh, social media. Small businesses using WhatsApp for sales and business, where we’ve seen people keeping in touch. There’s so many good things on WhatsApp, but also so much poison in WhatsApp because of the way that it has been used for misuse. Misinformation, disinformation, and just not understanding what the facts are. And during COVID, we saw Indians pay for this with their lives. And therefore, we must pay more attention and do everything we can to help. India will not be caught up like America and so many other places.

Abhish K. Bose: How can fact-based discourse be revitalized through strengthened fact-checking, media literacy, and transparency measures? What role did the corporate media’s pursuit of profit and influence and social media’s amplification of misinformation and polarization and erosion of trust in institutions played in this?

Sreenath Srinivasan: I’m a big fan of boom, boom, boom. all live and other such efforts in India. Then, they are in fact role models for what should happen in the U S having this quick, rapid response to lies that are circulated is really going to be even more important as we go forward. In elections around the world and just functioning as a civil society, we need to pay more attention to the problem that the ecosystem itself is corrupted and in India we see that there is so much corruption. Attention given to mainstream media outlets that just make so much noise and people shouting at each other and all of this has caused a breakdown in what is truth and what is real in, and that’s, that’s, that’s something that we are going to continue to struggle with as we look at everything that’s happening.

Abhish K.Bose: What are the underlying drivers of the alarming moral decay in politics where leaders sacrifice principles for power and parties compromise?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: Compromise values for electoral gains. I can tell you that, again, this is a global phenomenon and we have seen the question of country over party. Is that something that politicians are willing to do? There was a time when politicians were willing to have high standards and would, in fact, consider putting their country over their party and their narrow, narrow political, uhm, options and narrow political gains. But that is not the case. We have lost more than moral clarity. We have lost, uh, what are the standards of what makes something right and what makes something for right now. And that’s something we have, we’re missing in global politics and we need to fix that. Unpacking the Moral Guidelines Bankruptcy of Politics,

Abhish K. Bose: What symbiotic relationships between political ideology, social media, institutional decay have normalised the prioritisation of power over principles?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: We have seen this again and again in so many parts of India and how politics works. That, what we have seen, we also want to say that on top of everything else, we have added the issue around, uh, around business interests, infecting the media. Media has become so successful in making so much profit, that it thrives on division. It thrives on anger. And we are seeing that on, of course, on Indian television every night. But also on social media. There’s an old saying about American television, that it makes so much money doing its worst, that it has no incentive to do its best. And therefore, the worst aspects of American television, uh, always come to the forefront. But there was something, as this was said, in the 1950s and 60s, not today. So it has all just become much much worse in the time since this was said.

Abhish K. Bose: What accounts for the alarming erosion of accountability in Indian politics ? Could you explain about the change in culture that trickled this transition?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: I want to be very careful that I’m not an expert on Indian politics, Kerala politics, beyond what I read and what I understand, but I am paying very, very close attention to the Indian politics, and I need for all of us to be thinking about how do we fix this, and we want to do that by saying that journalists need to go back to their, to the basics. What is real? How do people understand it? And how does it feel? How does it affect people’s lives? Uh, the kind of things that get attention, uh, have always been a problem. There’s an old saying, by the time the truth puts on its pants, the lies have gone around the world. Right? That’s how quickly things move. And this is, again, before, The internet. The internet has just accelerated all of this. On top of this, we need to add the problem of AI. AI is going to make things more real-looking and real-sounding, and that will, therefore, cause more chaos in everyday everything we see. So, how do we adjust the way we think? What is the obligation of journalists and other members of civil society to deal with these issues?

Abhish K. Bose: What are the implications of India shifting democratic landscape on the intersectionality of social justice, economic development and cultural identity? How can policy makers balance competing interests and values to foster inclusive growth and social cohesion?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: I want to say that this is such a refreshing set of questions because I never get questions like this. Thinking about intersectionality, for example, is a new concept, new-ish concept in, uh, uhm, you know, that came in the U.S. It’s been around for a while, but came to the U.S., uh, uh, for people to understand after seeing what happened with the pandemic, that you have, you know, in, uh, there’s an intersectionality of race and class in the health story of the pandemic. America had such deep problems. 5% of the world’s population, 20% of the world’s death, deaths, deaths in COVID. We saw that problem in India as well, that if you aren’t given the right information at the right time, you will suffer. We saw this in the United States, in successive hurricanes that came, uh, just before the election, and because the hurricanes, because so many people in the U.S. Keep saying the governments are bad, politics is bad, don’t trust the government, don’t trust the government, then when the government tells you there’s a hurricane coming, you’re not going to listen. That is one of the issues that we have seen, and we are paying the price for that. Thousands of people are unnecessarily affected by these issues.

Abhish K. Bose: To what extent has the neoliberal economic order contributed to the commodification of politics in India? And how is this impacting the representation of marginalised groups and the delivery of public services?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: I think, India and America, this is one way in which things are different. In America, there are so many regional and local news outlets that cover these issues. Just a town, a city, a neighborhood, uh, a state in very tight, very, uh, intentional terms so that people can understand what’s happening. Accountability journalism is big in the U.S. now. India, as we know, has such a strong media system, but so much of it is national, so much of it is regional, but it isn’t accountability journalism, and that’s one of the things we’ve lost. There’s some, but nothing to the extent we need. In America, we have those things, and have also seen 2,900 newspapers fold in the last 25 years. Just think about that. 25,000 journalists have lost their jobs in the 21st century. Imagine the chaos that would be there in India if those were the rates at which these publications were closing. So we need to be paying more attention to that. All of this is directly tied into politics as well.

Abhish K. Bose: How has the digital revolution reconfigured the relationship between citizens, the state, and information in India? What are the trade-offs between digital governance, surveillance, data privacy?

Sreenath Sreenivasan: These are such important items, and India needs to be a leader in this, to say that we are going to make sure that our, there’s better hygiene in our information ecosystem. That itself will help. So thank you very much. Uh, so is the problem with seedless dates? So, if you buy a date and it’s seedless, there’s a good chance that in a factory somebody chewed the seed out and then put it into the system to sell these dates. Now, let’s presume for a moment that somehow this happens, that people are biting, putting it in their mouth. It is so unlikely that this is happening, but let’s say it’s happening. If you, as a consumer, cannot distinguish between a chewed version of a date or a pre-chewed version of a date, no matter how lightly chewed, then that’s on you. So, these ways in which things are sent out, and they are sent to divide, they’re sent to cause anger, they’re sent to hurt. They’re sent to trouble. And we need to check every time before we hit forward on WhatsApp, is this true? Do I trust this? And will my circulating this further help my family, my neighborhood, my city? My country, or will it just make things worse? My philosophy about this has been true since the year 2000. If it’s too good to be true, or it’s too bad to be true on the internet, it probably is. Because the more it inflames, the more unlikely it is to be accurate. That doesn’t mean there aren’t problems that should be reported on and should be shared, but what is your role in that? And that’s one of the questions we need to ask much more in India and elsewhere. Thanks.

ALSO READ: ‘A people’s movement can only stem corruption in the Indian society’