While an IMF bailout may provide short-term relief, Pakistan’s economic woes are deeply entrenched and require comprehensive structural reforms to address underlying deficiencies in infrastructure, governance, and fiscal management, writes Dr. Sakariya Kareem

The exacerbation of power outages serves as the latest indication of Pakistan’s deepening economic woes, potentially precipitating a looming financial crisis fuelled by a burgeoning debt burden. Pakistan was enveloped in darkness as its aging power grid struggled to meet the nation’s electricity demands. This extensive blackout, one in a series of recurrent power failures, underscores the systemic challenges facing Pakistan’s fragile economy, susceptible to both natural calamities and the looming spectre of sovereign default. With Islamabad urgently seeking an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout, concerns persist that such measures may prove inadequate in averting a full-blown crisis.

The immediate cause of the January power outage was attributed to a voltage surge at a power station in Sindh Province, triggering a domino effect across the country’s grid infrastructure and leaving over two hundred million citizens without electricity for nearly a day. These recurring blackouts are symptomatic of the neglect and underinvestment plaguing Pakistan’s electricity grid, established prior to the nation’s independence in 1947 and largely constructed in the 1960s. Moreover, the reliance on imported fossil fuels to power the grid has become increasingly precarious, with prices skyrocketing following geopolitical upheavals such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The ramifications of persistent power outages extend beyond mere inconvenience, exacerbating Pakistan’s already precarious financial predicament. The blackout inflicted an estimated $70 million blow to the nation’s textile industry, a crucial pillar of its export sector. Meanwhile, Pakistan’s total national debt has ballooned to over $200 billion, equivalent to approximately 90 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) by late 2022, according to official statistics. A confluence of factors including rampant inflation, currency depreciation, catastrophic flooding, exacerbated budget deficits, and an unwieldy debt burden have pushed Pakistan to the brink of default.

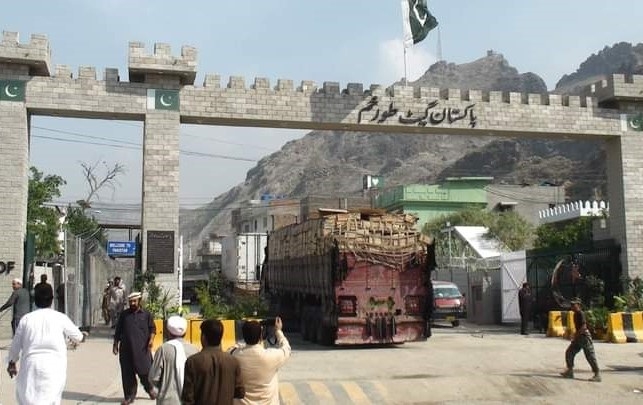

Pakistan’s persistent energy deficit, stemming from inadequate domestic production capacity and inefficient distribution infrastructure, has led the country to explore various avenues for importing electricity. Among these efforts, Pakistan has looked to neighbouring Central Asian countries such as Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which boast abundant hydropower resources, as potential suppliers of electricity. Bilateral agreements have been forged to facilitate the import of electricity, often involving the purchase of hydropower-generated electricity transmitted via cross-border transmission lines.

One significant initiative in this regard is the CASA-1000 project, which aims to establish a transmission line connecting Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to Afghanistan and Pakistan, thus enabling the export of surplus electricity from Central Asia to South Asia. Importing electricity from Central Asia offers Pakistan several benefits, including diversifying its energy sources, reducing reliance on fossil fuels, and addressing its energy deficit.

However, challenges such as infrastructure constraints, regional political instability, and financing issues may impede the smooth implementation of such projects. Nonetheless, these efforts underscore the importance of regional cooperation in addressing common energy challenges and fostering economic integration. Enhanced connectivity and energy trade between Pakistan and Central Asian countries have the potential to contribute to regional stability and prosperity.

The recent blackout exacerbates these economic challenges, with prolonged power shortages imperilling vital sectors such as agriculture and potentially necessitating increased food imports. Pakistan’s vulnerability to climate-induced disasters further compounds its economic woes, raising concerns among international stakeholders, particularly its key allies such as the United States and China.

For China, a protracted crisis in Pakistan poses risks to its substantial investments in the country under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with Pakistan being one of the largest recipients of Chinese financing. While Beijing has already scaled back its lending to Pakistan, sustained economic turmoil could deter further investment and undermine China’s broader geopolitical ambitions. Similarly, the United States, which has long viewed Pakistan as a strategic ally in combating terrorism, faces the challenge of balancing security imperatives with the imperative to address Pakistan’s economic vulnerabilities exacerbated by climate change.

In response to its mounting economic woes, Pakistan has sought assistance from the IMF, hoping to stave off default and shore up its dwindling foreign reserves. However, previous IMF-imposed conditions have sparked domestic opposition, and the proposed bailout is viewed by some as a temporary fix for deeper structural issues plaguing Pakistan’s economy, including chronic underinvestment in critical infrastructure such as electricity generation. In essence, while an IMF bailout may provide short-term relief, Pakistan’s economic woes are deeply entrenched and require comprehensive structural reforms to address underlying deficiencies in infrastructure, governance, and fiscal management. Failure to address these systemic challenges not only imperils Pakistan’s own stability but also reverberates across the broader geopolitical landscape, impacting regional stability and the strategic interests of key international actors.

ALSO READ: Pakistan, China agree to upgrade CPEC