China’s colonial boarding schools forcibly assimilate Tibetan children, banning their language and culture, raising fears of cultural erasure and calls for urgent international intervention.

A damning new report released by the US-based Tibet Action Institute has shed light on China’s deepening campaign of political assimilation in Tibet through a sweeping network of colonial-style boarding schools. The report claims that these institutions are being used not to improve access to education, but to systematically sever Tibetan children from their cultural, religious, and linguistic heritage.

According to the 62-page report, nearly one lakh children between the ages of four and six are currently enrolled in state-run boarding preschools across the Tibet Autonomous Region and other Tibetan areas under Chinese control. The figure rises sharply to over nine lakh children aged six to eighteen, who are also believed to be studying in such residential schools.

These institutions are not optional. Tibetan families are reportedly under increasing pressure to enrol their children in these facilities, which separate them from their homes and communities. In many cases, children are placed in schools located in towns or cities despite having local schools nearby. They are prevented from returning home even during holidays.

The report documents that within these schools, the Tibetan language is banned in the classroom and discouraged in general use. Tibetan children are taught exclusively in Mandarin Chinese and are denied the right to practise their religion or celebrate cultural traditions, both during term time and holidays. Even symbols of Tibetan Buddhism, such as images of the Dalai Lama, are prohibited.

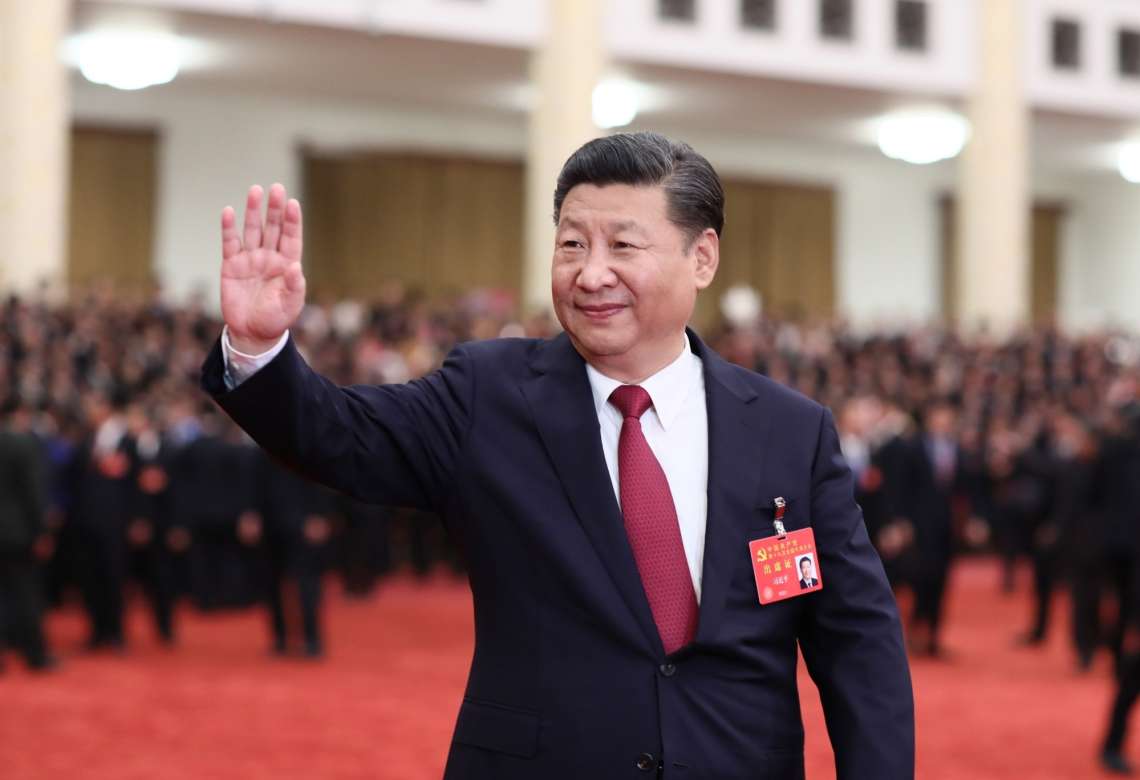

The report has drawn sharp condemnation from the Tibetan government-in-exile and the wider diaspora community. Namgyal Dolkar, a member of the Tibetan Parliament-in-exile, criticised the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) actions as a calculated attempt at cultural erasure.

“We are looking at a very categorically planned move,” she told ANI, “systematically set up by the Chinese Communist Party over the years to control the minds and brains of Tibetans. They’ve realised that targeting young minds is the key to long-term control.”

Dolkar pointed out the hypocrisy of Beijing, which has ratified multiple international treaties related to human rights, child protection, and cultural preservation — in addition to having constitutional guarantees for minority language and cultural rights. “Despite all this, they continue to violate these norms in occupied Tibet,” she said.

According to Dolkar, the CCP views Tibetan identity, when nurtured within Tibetan families and communities, as a threat. “Tibetan children raised in the embrace of their parents tend to grow up pro-Tibet, which is a major concern for the Chinese state. That is why they have made enrolment in these colonial boarding schools mandatory — not for educational improvement, but for political indoctrination.”

The term “colonial boarding schools” is not used lightly. The Tibet Action Institute and exile leaders draw a parallel with infamous colonial-era assimilationist policies, such as the Canadian residential schools for Indigenous children or similar systems in Australia. In Tibet’s case, the objective appears to be the transformation of Tibetan children into loyal Chinese citizens who identify more with Beijing than with Lhasa.

Tibetan activist and author Tenzin Tsundue highlighted the long-term risks. “What Tibet Action has found is horrifying,” he said. “About 100,000 children are being forcibly indoctrinated. The boarding schools are deliberately positioned in urban centres even when children have access to local day schools. This is not about access — it is about control.”

Tsundue noted that China’s so-called “bilingual policy,” which was initially rolled out in some Tibetan areas in 2009 and expanded thereafter, is proving to be a euphemism for monolingual, Mandarin-only education. “Our fear is that in 5 to 15 years, an entire generation of Tibetans will grow up knowing only the Chinese language, with no connection to their ancestral identity. This is cultural genocide in the most literal sense.”

The Tibetan exile community is now calling for urgent international intervention. They want human rights organisations, foreign governments, and UN bodies to pressure Beijing to halt these assimilationist policies and allow Tibetan children to be educated in their mother tongue and within their own cultural context.

The timing of the report is significant, with Tibet already facing heightened global scrutiny amid worsening human rights conditions. The exile leadership believes that bringing such documentation to light will not only strengthen their case at global forums but also help in rallying wider public opinion against Beijing’s actions.

“China is playing a long game,” Dolkar warned. “They want Tibetans to stop feeling Tibetan. That’s why it is so important for the world to act — not ten years from now, but today.”

The Tibet Action Institute’s report adds to growing evidence that Beijing’s efforts in the region go far beyond infrastructure and development, and instead target the very identity of the Tibetan people — starting with their youngest generation.