For someone who believes art cannot be made in isolation, and must reflect contemporary social and political realities, he insists that even till date he reads the society to make his theatre…writes Sukant Deepak

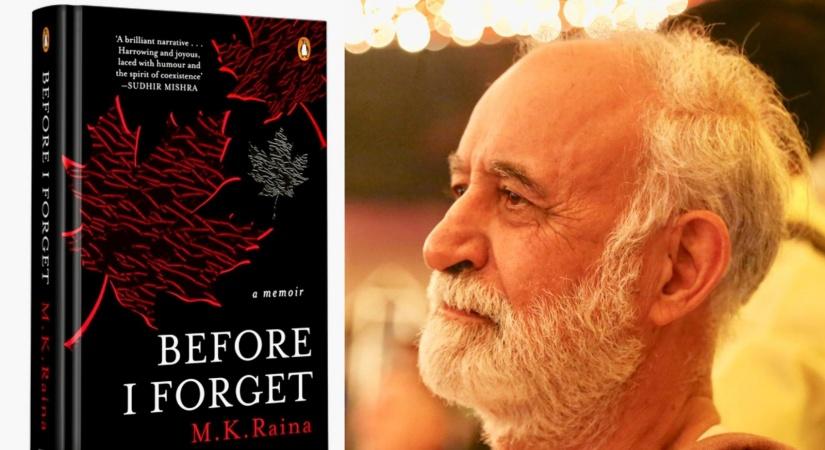

He makes it clear that the memoir is not about his theatre journey, nor the making of some of the finest theatre productions he has brought on stage, but in fact, about India and the many shades he has been a witness to.

Theatre director M.K. Raina’s memoir ‘Before I Forget’ (Penguin) starts from his childhood in Kashmir, the time when Sheikh Abdullah was arrested, his work as an activist post the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, the killing of theatre personality Safdar Hashmi, and his work with ‘bhands’ in Kashmir.

It was important for him to put it out all there — for these are vivid tales from a complex land where nothing is linear. He smiles, it is this aspect of India he has been a witness to, that precipitated the writing of the book.

“During the pandemic-induced lockdown, I sat back and recalled my life, and yes, was very surprised by whatever I encountered during all these years,” he told IANS. You may take the questions anywhere, but Raina will ultimately come back to Kashmir — the home he was forced to leave like his fellow Pandits.

For someone who believes art cannot be made in isolation, and must reflect contemporary social and political realities, he insists that even till date he reads the society to make his theatre.

“The Westernised version of ‘isolation’ is not for me. I can never do a play that has no socio-political relevance and does not reflect the echoes of the present times,” Raina said. OK, we are back in Kashmir now.

It was at the beginning of 2001, at a time when the Valley was burning, that Raina quietly went there to hold workshops and work with ‘bhands’. That was also the time when ‘bhands’ were completely prohibited by militants from performing. Even at weddings, there was no singing, no sarangi too.

“They had not performed for 10 years,” Raina recalled. “When I met them, they burst out crying, almost howling. I kept looking at them. There was so much inside them waiting to come out.”

Deemed un-Islamic, it was not easy to revive theatre in Kashmir’s countryside at a time when no auditoriums were functioning and colleges and universities were shut.

But Raina knew he had to make a start somewhere to reclaim the Valley’s cultural fabric, which in many ways is very egalitarian. “I had to enter through the needle hole quietly, otherwise, they would have shot me dead,” he said.

His friend suggested a hostel at an agriculture university deep inside forests and orchards, where he started taking a month-long theatre workshop attended by people from across districts, including those in South Kashmir. “It was almost a Gandhian way of living. We cooked together, cleaned dishes and washed our clothes,” he remembered.

During their rehearsals, people from around the village would start coming in as spectators. Slowly, word got out that a performance was being prepared. “On the day of the show,” Raina recalled, “hundreds of people in buses arrived. I was stunned. But it was also a hint for me to continue my work there.”

For a long time, he kept holding at least three workshops every year in the Valley. Stressing that it was not to make productions, but also a way to use theatre as a healing tool, Raina added, “There were traumatised children and women, the psychological damage in the society was so evident. I just hope I was able to do something through this great art form.”

For someone who trained 300 youngsters in theatre in Kashmir who went to make their theatre groups in different districts of the UT, Raina now points out that he did not want to come to the forefront, and explains precisely why he stayed away from the media during those times. “I did not want to be the hero,” he said. “Everything was done for a larger cause.”

Be it working in jungles, orchards or in an unfinished hospital, Raina remembered that hints were dropped that the militants were unhappy with what he was doing. He continued: “But then some people told them it was all for culture, and not some political cause — we never heard from them, considering the ordinary people were with us.”

Talk to him about art in a conflict zone and Raina stresses that he had to look over his shoulders 24×7.

“I was caught in stone pelting, a police raid, threats from militants … But what I learnt was a great lesson in patience, and in being reasonable. You cannot afford to lose your temper. Slowly, everybody started supporting us — villagers and traders in the Anantnag area especially,” Raina said.

When he did ‘Badshah Pather’, the adaptation of Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’, he would work in a clearing surrounded by mountains where people sat to watch the rehearsals. Remembering the setting reminiscent of a primitive Greek theatre, he said, “Those moments opened my eyes to that many possibilities that theatre can offer.”

Lamenting that the lack of funding has made him less active in Kashmir, Raina said, “Half of my life has gone into trying to garner resources. Besides the India Foundation for the Arts, nobody has come forward. What more can I say?”