The research team believes that these findings call for a shift in how cancer care is delivered. Emotional and social support should no longer be viewed as optional or secondary. Instead, they argue that psychosocial assessments and targeted interventions must become part of routine oncology care

Loneliness and social isolation may significantly increase the risk of death among people living with cancer, according to a large new study led by Canadian researchers from the University of Toronto.

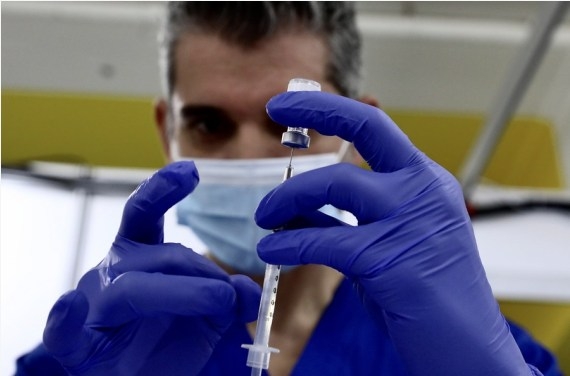

Published in the open-access journal BMJ Oncology, the study analysed pooled data from 13 studies involving more than 1.5 million patients worldwide. The results showed that loneliness was associated with an 11 per cent higher risk of death from cancer, even after adjusting for factors like sample size and clinical variation.

Researchers found that the effects of loneliness went far beyond emotional distress. Chronic social isolation may activate biological stress responses, disrupt immune system function, and increase inflammation—all of which are known to contribute to cancer progression and recurrence.

The study also considered the unique emotional and psychological burden that cancer patients face, particularly during and after treatment. Many patients experience a form of isolation linked not just to physical limitations, but to emotional disconnect from their communities, friends, and even close family members.

Factors such as the stigma surrounding visible treatment side effects, fear of recurrence, and the ongoing stress of managing appointments and symptoms can create an environment in which patients feel misunderstood and alone. Even the medicalisation of daily life, with repeated clinical visits and side effects like fatigue or cognitive impairment, can cut people off from their social networks.

The research team believes that these findings call for a shift in how cancer care is delivered. Emotional and social support should no longer be viewed as optional or secondary. Instead, they argue that psychosocial assessments and targeted interventions must become part of routine oncology care.

They suggested that support groups, counselling, and community programmes—often dismissed as “soft” components of care—can have a measurable impact on survival outcomes. The inclusion of these services may help reduce stress, improve adherence to treatment, and strengthen the immune response.

The implications go beyond cancer care. The World Health Organization has recently named loneliness as a major public health concern. Multiple studies now link loneliness to higher rates of cardiovascular disease, dementia, and early mortality. This new research adds cancer to the growing list of illnesses that may be worsened by social isolation.

With survival rates improving across many forms of cancer, long-term well-being and quality of life are increasingly being recognised as essential parts of care. But this study warns that without addressing the emotional and social needs of patients, medical success alone may not be enough.

The researchers acknowledged that more high-quality studies are needed to confirm the link between loneliness and cancer mortality. Still, they believe their findings are strong enough to warrant immediate attention in both clinical and policy settings.

As the cancer community continues to evolve, integrating emotional and social care could be the next frontier. Because for millions of people fighting cancer, healing may not come only from medicine—but also from meaningful connection.