Shifts in the relative standing of both America and China in various elements of power, including military spending, are possible and indeed already emerging as policy directions and circumstances change…reports Sanjeev Sharma

China’s comprehensive power has dropped for the first time in four editions of the Asia Power Index, as the country lost ground in half of the Index’s measures of power in 2021 — from diplomatic and cultural influence to economic capability and future resources.

As per the Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index, this contrasts with the year before when Beijing emerged diplomatically diminished from the pandemic but was holding ground in overall power, and to 2019 when it netted the highest gains in the region.

“On current trends, Beijing is now less likely to pull ahead of its peer competitor in comprehensive power by the end of the decade. Importantly, this change suggests that there is nothing inevitable about China’s rise in the world,” the report said.

Shifts in the relative standing of both America and China in various elements of power, including military spending, are possible and indeed already emerging as policy directions and circumstances change. Across the range of feasible outcomes, however, it appears unlikely China will ever be as dominant as the United States once was, it added.

However, in a contested strategic environment, China’s rise relative to the United States is more fragile than many may believe, including those in the one-party state.

However, with the onset of Covid-19, an emphasis on economic self-sufficiency and geoeconomic security has become part of a much broader inward turn. This shift has hurt China’s relative advantages elsewhere.

In 2019, for instance, China benefited from more arrivals of non-resident visitors from the region than any other country, including business travellers, tourists and students. But in response to the pandemic, China has installed one of the world’s strictest systems of border control and quarantine. This has significantly disrupted international travel to and from China with a pronounced knock-on effect on people-to-people links with the region — a key driver in the country’s cultural influence.

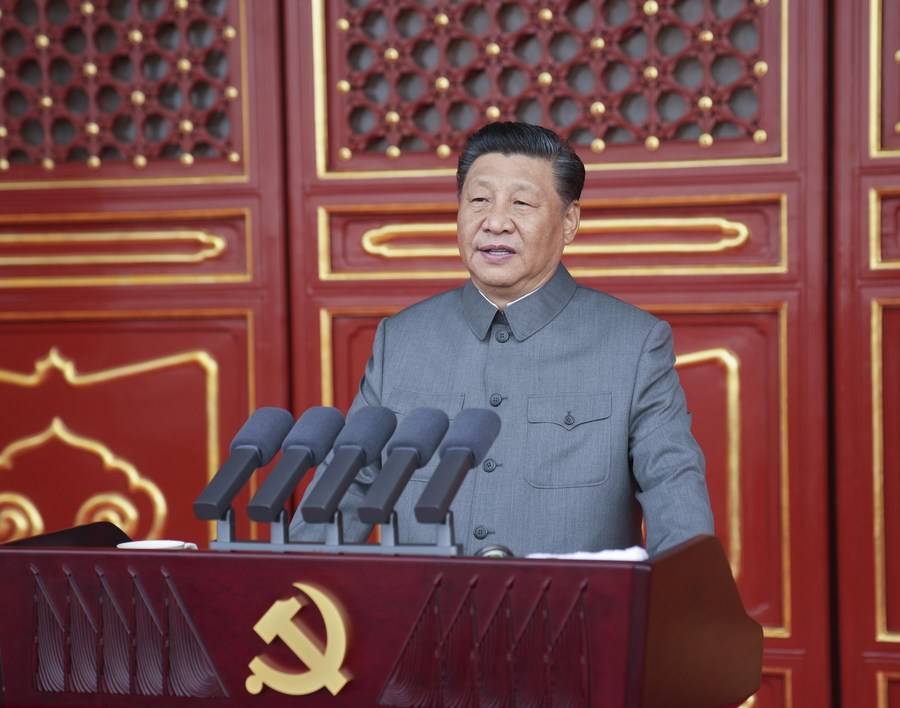

The report said China’s inward turn appears also to have depressed its diplomatic influence. Beijing’s pole position in that measure has been very narrowly overtaken by the United States in 2021. Despite a frenetic pace of regional diplomatic activity by senior Beijing officials, President Xi Jinping himself has not left the country for almost two years. His leadership on the international stage this year was outranked in the Index’s regional expert survey by the leaders of the United States, Russia and even Singapore.

Nowhere has China lost more ground than in the future resources measure. A growing burden of structural weaknesses weighs on the country’s prospects. These include a rapidly ageing population, water scarcity in stretches of the country, and vulnerability to flooding in others, a heavy debt load, and a political system that spends more on projecting power inwards, on internal security challenges, than it does on projecting it outwards, on military expenditure.

China’s economy at market exchange rates will still likely overtake that of the United States. But there are inherent limits on the speed at which China can continue to grow beyond 2030. Significant domestic challenges await in coming decades. Few policy levers exist to turn around the decline in its working-age population; productivity growth is slowing, and China’s investment heavy approach for driving the economy will produce diminishing returns over time, the report said