To her family’s consternation, she insists on travelling to Pakistan, simultaneously confronting the unresolved trauma of her teenage experiences of partition, and re-evaluating what it means to be a mother, a daughter, a woman, and a feminist…reports Asian Lite News

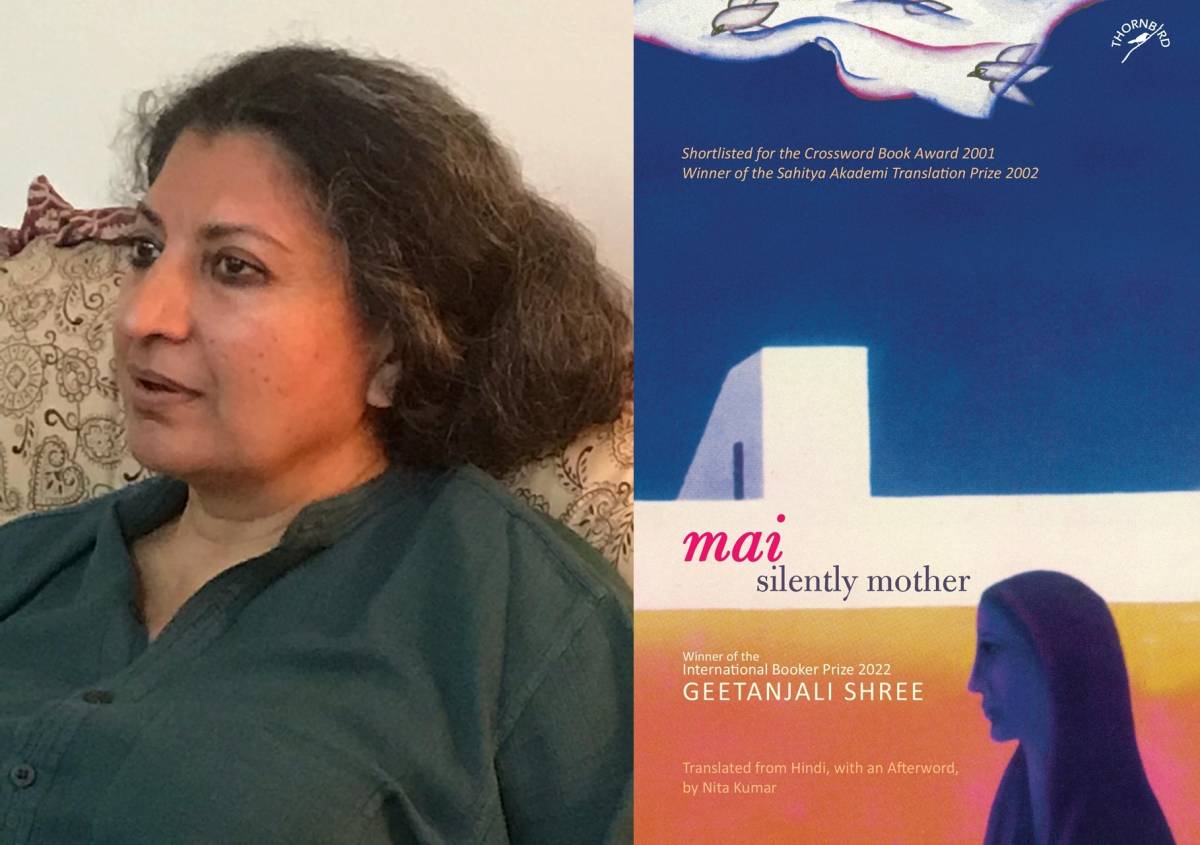

Not only has Delhi-based author Geetanjali Shree’s ‘Ret Samadhi’, translated into English by American writer-translator Daisy Rockwell into ‘Tomb of Sand’ achieved a new milestone by being the first Hindi literary work to win the prestigious International Booker Prize, it has also asserted no matter the language, but human emotions are also connected by common emotions and metaphors.

Speaking to IANS when the book was shortlisted for the coveted prize, she had stressed, “Of course, this is something I have always known.

Otherwise all these centuries, we would not be loving and relating to art and literature from vastly different countries of the world. Human (and other) life is about the same emotions and experiences, albeit couched in different ‘cultural’ details. It is when the former touches our soul that the latter ceases to be alien and only adds more dimensions to our experience.”

Reacting to the Booker, she said: “This is a bolt from the blue, but what a nice one. I never dreamt of the Booker, I never thought I could. What a huge recognition, I’m amazed, delighted, honoured and humbled,” says the author, who was in disbelief during her acceptance speech, “There is a melancholy satisfaction in the award going to it. ‘Ret

Samadhi/Tomb of Sand’ is an elegy for the world we inhabit, a laughing elegy that retains hope in the face of impending doom. The Booker will surely take it to many more people than it would have reached otherwise, that should do the book no harm.”

‘Ret Samadhi’ centres around a north Indian 80-year-old woman who slips into a deep depression after the death of her husband and then resurfaces to gain a new lease on life. Her determination to fly in the face of convention including striking up a friendship with a transgender person confuses her bohemian daughter, who is used to thinking of herself as the more ‘modern’ of the two.

To her family’s consternation, she insists on travelling to Pakistan, simultaneously confronting the unresolved trauma of her teenage experiences of partition, and re-evaluating what it means to be a mother, a daughter, a woman, and a feminist.

Talking about how the award-winning book was conceived, she remembers that it was the image of an old woman lying with her back turned to everyone in a joint family and apparently with no interest in living any longer that set her off. “My curiosity grew as to is she turning

her back on the world and life or preparing to get up into a rejuvenated, reinvented new life! From there the novel took off. It was a long journey full of fun, pain, joy, anxieties, the works,” she said.

But winning a major prize is not something she will let effect her writing. The author is clear that writing must never be extraneously motivated or influenced. “I write to express as best as I can, as creatively and sensitively as I can, and that is the only expectation

I am propelled by. I let no one tell me what, when, how I must write.”

The author whose works have been widely translated into several languages including French, German, Korean and Serbian, feels that translation is dialogue and communication. It is never a fixed, frozen and complete exchange. “It is ongoing, live and enriching some

things are explained better, some remain confounding, just as in any communication. Some things may also get lost, but some things also get added. Just as when two people talk, they enrich each other and enlarge each other’s way of seeing, being, and experiencing, so is also the communication underway in translation.

The gains of it are immense. One cannot fear it for the risks that may be in there too. Communication is worth it, risky or not! Dialogue, which is what translation is, is the best thing in human life and the way forward.”

ALSO READ-‘A Passage North’ in the final six of Booker shortlist