Washington is stumbling into another version of India’s own 1962 war with China, writes Prof. Madhav Das Nalapat

The Sunday Guardian (TSG) was among the first media outlets in the world to be barred not just physically but online by the PRC in 2020. It does not therefore come as a surprise that academics known to be cosy with the CCP spew venom on the paper as well as on some of its contributors. A recent gem of vituperation against TSG was by an individual who claimed to be a professor in Australia. According to her, to talk of a Sino-Wahhabi alliance was a flight of fantasy. What she makes of the military exercises taking place that involve Turkey, Pakistan and China are not known.

Perhaps she believes that President Erdogan is a true follower of Kemal Ataturk, the leader who secularized Turkey, and that Pakistan run by its army is an exemplar of what a tolerant, liberal democracy ought to be. Small wonder that non-Muslims in that enlightened country have dropped from around 37% of the population to less than 2% over the 75 years that Pakistan was carved out of India. Whether it be Somalia or Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, the PRC has cordial relations with each of the countries that openly practise discrimination against significant elements of the population.

Not just the lady professor but a few other Australian academics as well have responded especially sharply in public to reports in TSG that the CCP was steadily expanding its control over several of the South Pacific Islands, now that it has created and claimed ownership rights over several islands it has built in what ought to be called the ASEAN Sea but is termed the South China Sea for some reason. Just days ago, Daniel Suidani, one of the few South Pacific leaders who were brave enough to call out the CCP, was voted out of his job as Prime Minister of Malaita, a part of the Solomon Islands.

Supporters of his warned of the well-funded, remotely directed operation to topple him through a no-confidence motion in the legislature of that state. Their warnings went unheeded by policymakers in Australia and New Zealand, who have taken on themselves the task of assisting the South Pacific Island countries to resist the tentacles of the ruthless, expansionary moves of a nearby superpower. Suidani had protested against the action by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare of the Solomon Islands of shifting diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing.

From that time onwards, for more than two years he was the target of the China-leaning lobby in the Solomon Islands, and they finally succeeded in persuading (through methods that are not difficult to guess) enough legislators to get passed the no-confidence motion.

Australia and New Zealand are far closer to India or to Indonesia than they are to Ukraine or Germany, and yet both appear to have lost any enthusiasm that they may have had in preventing the spread of authoritarian tentacles in nearby waters. Instead, both Auckland and Canberra seem to be obsessed with the conflict that has been taking place between Russia and Ukraine. In Asia, with the exception of South Korea, Taiwan and Japan, no other country has thus far shared the substantially greater priority given by New Zealand and Australia to Europe rather than to the world’s biggest continent.

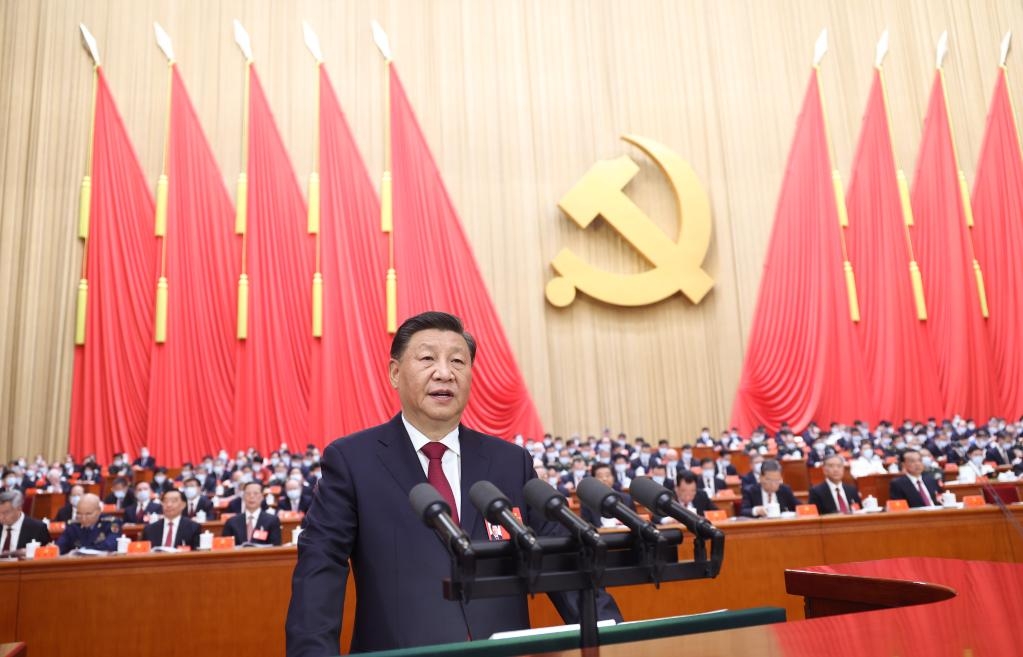

Even in the case of South Korea, Taiwan and Japan, there has been from the Biden administration none of the gifts of advanced weaponry that has been sent by Washington to Ukraine. This when any one of this trio is much more vital to the national security of the US than Ukraine is. CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping is into an unprecedented third term in his job. Having achieved that, simply for reasons of survival, he needs a fourth term. Unless he is able to fulfill his promise of recovering the “lost lands” (i.e. those territories that belong to the PRC only in the imagination of the CCP leadership), even the usually docile CCP Central Committee may balk at giving him yet another term once he completes his present term within five years.

Which is why this period is one of extreme danger to Taiwan in particular, the country that the CCP proclaims is a “renegade province”. It must be said that even though the members of NATO have not directly entered the Russo-Ukraine war, a seamless flow of weaponry has gone to Kiev, not to mention sanctions on Russia that only its abundance of resources has shielded that country from economic collapse. In particular, China is by far the biggest purchaser of Russian natural resources, a factor that has enabled Moscow to shrug off the impact of western sanctions.

The fall of Taiwan would critically weaken the defences of two US treaty allies, South Korea and Japan, and would have almost as severe an effect on the Philippines. The ripples would then spread to Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam. Given that, why President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken still cling to the doctrine of “strategic ambiguity” when it comes to defending Taiwan in the event of an attack by China makes no sense.

Rather than prevent a conflict by humouring the exaggerated sensibilities of Beijing, the doctrine of strategic ambiguity only pushes forward the prospect of a kinetic attack on Taiwan by China. Together with strategic clarity on what is an essential reaction in the context of overall US interests, the Biden administration needs to put in place a mechanism to begin delivery of advanced weaponry to Taiwan in the way this has been done for Ukraine.

The visible eagerness of the Biden administration to downplay the significance of the strategic slap that the PLA administered to it in the form of a mammoth spy balloon has cast doubt in several corners of the Indo-Pacific about the extent of resolve of the White House to resist authoritarian expansionism in the region. Seeking a diplomatic America-Chini Bhai Bhai is as much a chimera as India’s efforts to get a military-controlled Pakistan to sheathe its terrorist talons and choose the path of cooperation rather than conflict with India.

Given the steady salami slice upon salami slice of the advance of PRC expansionism within the Indo-Pacific, Washington is already stumbling into another version of India’s own 1962 war with China, except that this time around, it is in slow motion. When or even whether this oncoming reality will become evident to the Biden White House is unclear.