Professor K.P. Kannan, a former Fellow and Director of the Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum is currently a Honorary Fellow there. He is also the Academic Chairman of the Laurie Baker Centre for Habitat Studies in Trivandrum. He was a member of the International Panel on Social Progress, a collective initiative of social scientists from different parts of the world, which prepared a global report on Society in the 21st Century in June 2018 (published by Cambridge University Press).

Professor Kannan has had several UN assignments, the most important of which was as an Expert Member in the Technical Secretariat of the World Commission on Social Dimension of Globalisation constituted by the ILO in Geneva (2002-03). During 2005-09, he was a Member of the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (NCEUS) appointed by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that prepared a number of major reports on the informal economy and informal workers in India. In 2008, he was conferred the first VV Giri Memorial Award for his contributions in the area of social security for workers in the informal sector. He was awarded a National Fellowship by the India, the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) during 2016-18.

Professor Kannan has authored, co-authored, or edited twelve books as well as several research papers. His books include Poverty, Women and Capability: A Study of Kerala’s Kudumbashree System, LBC, 2023; Interrogating Inclusive Growth: Poverty and Inequality in India, Routledge, 2014; and The Long Road to Social Security (edited jointly with Jan Breman),OUP, 2013. In an interview with Abhish K. Bose he discusses the economic inequalities prevailing in India reminiscent of the post partition period and a number of issues which deals with the political economy of the country.

Excerpts from the interview

1. In India, economic inequalities have aggravated between the ultra-rich and the poorest, reminiscent of the 1940s -the partition and its miserable aftermaths. Given that equality is basic to the health and vitality of democracy, what dangers do you perceive the present trend as harbouring for the survival of democracy in India? Please examine this issue also because economic inequality, or developmental differential, plays a part in Hindu-Muslim alienation, which has intensified of late in India.

KPK: Increasing economic inequality is one of the sharp outcomes of the neoliberal economic policies followed by most countries in the world since the collapse of the Soviet Union. India is no exception. By mid-1970s India managed to bring down its pre-independence economic inequality to some extent by its mixed-economy policies and state interventions. But this trend got reversed since the initiation of neoliberal economic reforms since 1991. Economic inequality is certain to affect the democratic process as we are witnessing today in the form of the role of money in elections. When it is also accompanied by the rise and strengthening of crony capitalism it exerts an undue influence in economic and social policies. At the same time, one should also remember that India is a land of manifold inequalities as in hierarchical social structure, gender inequality, as well as spatial inequality manifested as rural-urban inequality in economic and social development. My own work in documenting the intersectional nature of economic inequality from the point of the ordinary people is contained in Interrogating Inclusive Growth: Poverty and Inequality in India (published by Routledge in 2014). The social dimension of increasing economic inequality is not limited to the Hindu-Muslim divide but an increasing gap between each of the disadvantaged groups compared to what I called the ‘Socially Advantaged Group consisting of upper caste Hindus, Jains, Zoroastrians, Sikhs, and Christians. The increase in social inequality as between the bottom groups of SC and ST and the socially advantaged is the highest. The only field where social inequality has reduced somewhat is in education taken as average years of education. For my research in this area of social inequality see, K.P. Kannan (2019), India’s Social Inequality as Durable Inequality: Dalits and Adivasis at the bottom of an Increasingly Unequal Hierarchical Society, Working Paper No. 488, Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram (Also published as a chapter in Reclaiming Development Studies: Essays for Ashwani Saith,edited by Murat Arsel, Anirban Dasgupta, and Servaas Storm (published by Anthem Press, 2021).

2. In his latest book ‘ India is broken’ economist Ashoka Mody argues that the socialist policies of Nehru and Indira Gandhi governments paralyzed economic growth which hinges on the presumption that socialism continues to hamper India’s economic prospects. Has commitment to socialism weakened the foundation of democracy in India by clogging development with excessive concern for the poor? To what extent can the ills of the present state of India be blamed on Nehru?

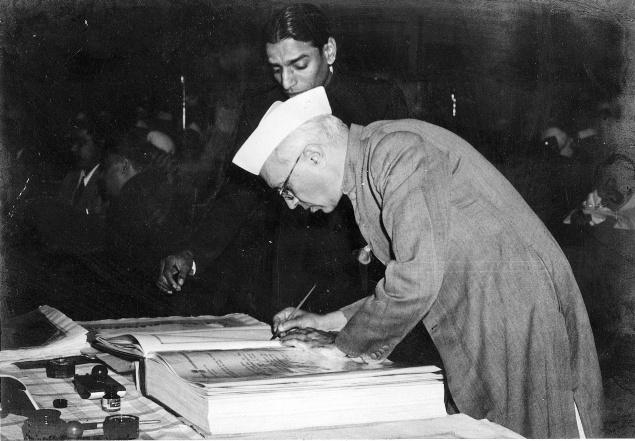

KPK: I do not agree at all with the view taken by Ashoka Mody. He is a distinguished member of the alumni of the Centre for Development Studies as well as a colleague for some time. Jawaharlal Nehru was not just the first Prime Minister of India but a towering architect of modern India even before independence. Not only he represented a secular and modern vision for independent India but also built it on the foundations of the best principles and practices of Indian civilization such as the plural nature of its religious heritage, an innate ability to fuse foreign civilizational cultures into its own, free thinking as represented in its multiple philosophies. At the same time, India was a vanquished economy at the time of independence having been drained of its resources for more than one-and-a-half century by British colonialism. The Great Bengal Famine and several famines and droughts during the colonial period is but one manifestation of this draining. Added to this was the economic, social, and psychological disruptions of Partition as well as the limited foreign exchange that was not readily available to the country. It was also a time when a huge majority of people looked up to the Soviet Union as a model for economic and social emancipation. But Nehru and his team were strongly committed to a democratic polity and enshrined it in the Indian Constitution the value of which is now being increasingly realised even by the critics of his times. He knew the multi-structural nature of the Indian society and economy and wanted to develop it through the instrumentality of national planning. But he and his team also realised the practical limitations and adopted a mixed economy approach in which certain basic sectors of the economy called the ‘commanding heights’ were to be led by the state through the establishment of a public sector. It was neither explicitly socialist or capitalist but social democratic or what was then called ‘a socialistic pattern of society.’ This approach pulled the country out of its deep economic backwardness manifested by a growth rate of well over three percent per annum compared to less than half-a-percent during the five decades before independence.

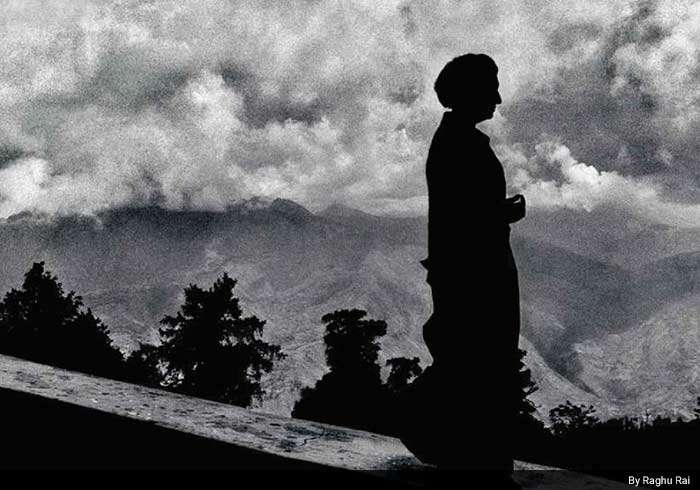

Beginning with 1962, the Indian economy went through a difficult period burdened by the war with China and then Pakistan, death of Nehru and the break-up of the Congress, war with Pakistan in 1971, droughts, and a higher rate of population growth than expected in the planning framework. The relative decline is clearly post-Nehru. Added to this is the semi-authoritarian style of Mrs Indira Gandhi and the emergence of political cronyism. Chief Ministers were picked from cronies within the Congress Party and it also finally resulted in weakening the Centre-State relations. By early 1980s western capitalism was clearly winning with its agenda of neoliberal economic reforms that suited the interests of the increasingly powerful finance capital. The final nails in the coffin of national economic development of many developing countries were thrust with the implosion of the Soviet Union and the formal establishment of the World Trade Organization declaring an all-encompassing process of globalization. China had already changed its tack with sweeping economic reforms embracing the market principles as directed by its state. India too had to follow with the collapse of the sources of cheap oil from Iraq as well as the market for trade in the former socialist bloc.

Given this understanding, I do not see any reason to put the blame on Nehru and the Nehruvian vision that encompassed not just the economic realm but also social, political, and international relations. It was a Middle Path, let us say Budha’s Middle Path. The relevance of this middle path is now increasingly becoming a necessity as the world is moving away from the neoliberal globalisation because it has not helped the rich western capitalist countries to continue their economic and, by extension, political hegemony over non-western countries. I think we will be compelled to rediscover the Nehruvian vision and its path as time goes by and the challenges before India becomes tougher and tougher both internally and externally.

3. Is Indira Gandhi responsible for the increasing political and economic corruption in post-Nehru India? What about the Total Revolution movement led by Jaiprakash Narain? What about the active agents in the public sphere such as the media, religious institutions, and judiciary in countering the increasingly corrupt practices?

KPK: As an academic, I do not subscribe to the view that the increasing corruption of politics and economics in India is solely to the due to personality of an individual. At the same time, if the individual is a powerful leader, he or she has the capacity to change the situation for the better. On the other hand, if it suits the logic of clinging on to power the leader will not hesitate to indulge in corrupt practices. That is the lesson of history. The struggle for power within the Congress led to the emergence of Indira Gandhi as an undisputed leader within her party and that led to a series of negative consequences to the polity and economy in the short as well as long run. The JP movement gave a lot of hope in the initial stages given the track record of Jaiprakash Narain but his followers were a motely crowd of clearly communal right-wing parties, parties oriented towards socialism with a core agenda for social justice (read caste based social justice) and others with an agenda for power-grabbing. It was inherently unstable and it was no surprise that they disintegrated within a short span of time paving the way for the return of Indira Gandhi and her Congress Party. She provided stability and determination as well as a concern for the poor that was addressed through populist policies of welfare benefits but not long-term institutional changes and/or a concerted programme for education and employment creation.

During the Emergency (1975-77), most of the media as well as other formal institutions did not provide much of a fight. However, the judiciary always kept a window of hope by not wholly following the agenda of the leader. Resistance was there among several groups as well as some intellectuals and some media institutions. People at large perhaps realised the gravity of the situation in suspending all civil rights and decided to act when national election was announced. And they used this democratic weapon, given to them by the Indian Constitution, to great effect

I do not think religious institutions got very much worried by the Emergency or the semi-authoritarian style of government of Indira Gandhi. In history religious institutions usually sided with state power unless they are attacked.

4. Before economic liberalisation, especially during the period of Nehru, the Indian economy is characterised as working under a dirigisme regime i.e. with positive intervention by the state in economic policy and planning having a lot of control. It also necessitated control of foreign exchange rate and its movement. Is this approach that led to what some call ‘Hindu Rate of Growth’?

KPK : As I said earlier a newly independent India did not want to take sides in a bipolar post-second World War era. It wanted to preserve its national sovereignty in both political and economic matters. At the same time, it did not believe in shifting itself off from either side of the Cold War leaders viz., United States and Soviet Union. As in the case of many other large developing countries it also adopted an import substitution strategy about industrialisation. That is how it laid the foundations for a heavy industry in many critical sectors that many now seem to forget. It required control and interventions in foreign exchange rate and its flow given the paucity of foreign exchange. This was the case with most developing countries. Only some small developing countries such as Taiwan, South Korea and Pakistan decided to align with the western block led by the United States that gave them access to foreign capital, external market for their products, development aid and so on. Some countries like South Korea and Taiwan had political compulsions to be a subordinate ally of the United States. But they used the opportunity to work hard, organise their economy for innovation, etc under military dictatorships and economically grew fast and became prosperous as appendage economies. Some countries like Pakistan and Philippines failed given their inefficiencies in internal economic system.

It was Professor Raj Krishna, an eminent economist, who called the below 4 percent economic growth as ‘Hindu Rate of Growth’ because it was not enough for India to solve its basic problems. This is because the capacity of the Indian economy to save and invest was so low (around 5 percent immediately after independence) and it grew slowly but steadily to around 20 percent by the mid-1970s. But this growth rate acquired the meaning of a ‘sloppy or slow performing economy’ by its use widely in the media. In terms of the historical experience of economic development before 1945, three to four percent was a high-performing one. As I said earlier this so-called Hindu Rate of Growth was much higher than what it was before and it laid the foundations for a faster rate of growth subsequently. We could have certainly done better but in a democracy every change must be a negotiated one, not one ‘ordered’ by the top as in the case of China. China decided to enforce a ‘one child per family’ policy and it enforced it ruthlessly. When India tried a milder version during the Emergency it got backfired because people saw it, rightly so, as an intrusion into their personal freedom. China could mobilize the savings in the economy into the coffers of the state and increase its investment rate. This does not mean that democratic India’s record in economic development was better than China. Many other factors also played their role in China’s experience such as raising the educational, skill and health levels of the people, abolishing private ownership of land, and pursuing a policy of full employment till the end of the 1970s. It then used this ‘broad base’ to get special treatment from the United States to access their technology and market but adopting an anti-Soviet Union policy in the realm of international politics. This opportunistic set of policies by aligning with the capitalist west led by the United States has not yet been adequately acknowledged and analysed in the development literature.

Blaming the pre-neoliberal economic reform period as ‘Hindu Rate of Growth’ is like blaming the parents by their currently educated and rich children for not being fast enough in enriching the family. What they forget is the sacrifices of the parents with limited means in educating the children and creating better opportunities for them to get educated in the newly expanded public provisioning of education and health that become the basis for the richer children to get access to both domestic and foreign opportunities for employment in the private sector.

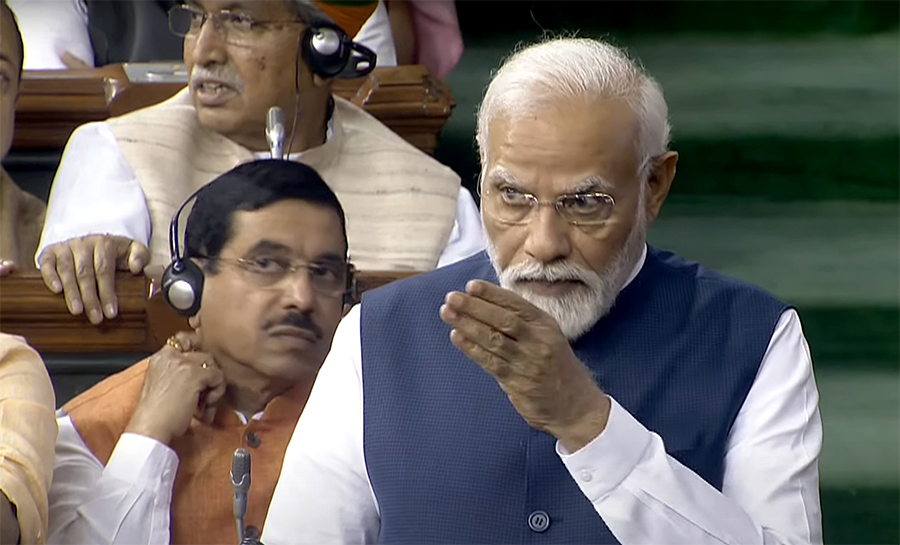

There is also a danger in glorifying the higher rate of aggregate economic growth when it is accompanied by increasing inequality. That means the disparity between the poor and the rich are widening although the poor may be benefitting a small increase in income in absolute terms. This kind of growth – inequalizing growth – is a sure recipe for increasing social tensions and conflicts as we are now witnessing. Despite high aggregate growth, the backlog of poverty, low education and health status, inadequate employment let alone decent employment are the order of the day in our country. Even the rich countries are now witnessing the consequences of their increasing economic inequality. For them globalization has largely meant shifting of jobs by their capital to low-wage countries and an increase in private capitalist accumulation. This has given rise to the emergence of right-wing political movements who locate the problem in migration especially of those who do not look like them. It also becomes a fertile ground for authoritarian leadership. Democracy itself is being threatened as in many countries that we usually called ‘advanced’ or ‘developed’ such as the United States and several countries in the European Union. The old communist left has lost its credibility because it never subscribed to the will of the people through a process of multiparty democracy. The left represented by social democracy in Europe did sustain longer the old left but now face an existential threat from right wing political parties.

A new democratic left is emerging in many large and middle Latin American countries. But that kind of hope is not currently evident in Asian countries. Africa is a mixed bag with more countries under authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes. At the same time, I think there are enough reservoirs of political energy as well as economic capacity across countries for creating a more representative, secular, and equitable governance and development thinking and programme of action.

My hope is that strengthening such a new path will produce a new democratic movement with more participation, decentralisation, gender and social justice and environmental sustainability based on basic principles of fairness, public morality and ethics that could become a new Middle Path.

5. India followed an active non-alignment foreign policy as envisioned by its first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru till the end of the twentieth century. But the shift towards a pro-western – largely a pro-US – shift is evident for sometime now. In economic realms it is much stronger than in foreign policy. Do you think such a shift will end in subservience to US interests?

KPK: There is no doubt that India’s embrace of neoliberal economic policies has landed it in the lap of the US-dominated economic world order. But it is neither an inevitable or a desirable one. That is why it is increasingly asserting its ‘independent’ positions and policies. In politics, especially those relating to national security and external economic opportunities, the Indian regime finds itself compelled to protect its national interests. Hence its neutral stand on the Russian-Ukraine conflict. Even when the head of the government sides with Israel, corrections and caveats are issued immediately not to give up its earlier position. There is also the question of accessing advanced technologies – both civil and military and sometimes dual – that the US and its allies have been averse to giving to India. In defence, the Russian willingness to not only supply final products but also share technologies has been a time-tested experience. The Indian regime is aware of that it has not been successful in attracting the expected level of foreign direct investment as opposed to foreign portfolio investment that seek immediate profits through the stock market. The Indian regime also knows that the dominance of the US dollar in international payments is more of a constraint than a facilitator of its national economic development. Its aspiration for a higher stake in multilateral financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank has not received a favourable response from the US-led western block. Given these realities, my sense is that there are limits to any Indian regime’s proclivity to align strongly with the Western countries. This will result in a relatively independent foreign and economic policy in tune with national compulsions.

6. Do you expect India attaining any worthwhile alleviation, in the foreseeable future, of the mounting unemployment distress that is spreading unrest among our educated youth? How is the AI challenge, already looming large over the world, likely to affect us in this respect?

KPK: The biggest challenge to raising the pitiable standard of living of close to two-thirds of Indians is the lack of decent employment that ensures them a living wage, employment security and access to social security. Despite the high aggregate growth performance of close to four decades, 90 (or a little more) percent of employment is informal in nature i.e. insecure employment. Half or a little more than half of the total employment in India is classified as ‘self-employment’ with earnings that are often below the average wage of casual workers. India’s poverty is largely of the working poor especially those who toil in villages as well as in urban informal sector. The exodus of such insecure workers during the nation-wide lockdown was just one manifestation of this employment insecurity.

Added to this is the declining participation of women in the workforce. Despite increasing their average years of education, reducing the number of children per couple, willing to work in jobs that are traditionally appropriated by men, women in India are an excluded lot as far as access to employment is concerned let alone accessing decent jobs. Much of the ‘jobless growth is a product of the introduction of advanced technologies because of international competition and the compulsions to increase labour productivity. But this should have compelled the national governments to rethink their ‘growth at any cost’ policy by focusing on employment creation as an objective. This is feasible in a country of vast areas and people and the developmental deficit in education, health, housing, rural infrastructurenot to speak of the urgent need for ecological regeneration and environmental sustainability. This question was addressed by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (known as NCEUS) that was appointed by the former Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh in 2004. The final report of the NCEUS argued for an employment policy that, by default, will address several basic problems being faced by the un- and under-employed as well as those in informal employment. I would remind the readers to examine this report titles The Challenge of Employment: An Informal Economy Perspective published by the Academic Foundation, New Delhi in 2009.

Given the pace of technological change India would find itself difficult to opt out of working and adapting the new technologies including AI but employment and social consequences need to be studied, understood, and analysed for designing a larger economic vision and approach to pursue a strategy of ‘employment with growth.’

7. Why does corruption remain endemic and impossible to eradicate in our society? Without containing corruption, is it possible for India to do justice to her true potential or do justice to the common man? The AAP, which got started with much fanfare about eradicating corruption, is now perceived to be getting infected. What measures would you suggest to contain corruption in India?

KPK: Corruption is like cancer. It will slowly but steadily corrode the basic values in a society and affect the welfare of most of the people. The minority of beneficiaries will benefit in the short run but will produce outcomes that will be disastrous to the development and welfare of the country. Corruption is a part of the concept of ‘rent-seeking’ to extract benefits in multiple ways by people who have the power and opportunitybut not entitled to such extraction. If the top layers of the regime indulge in rent-seeking in various ways, it will rapidly infiltrate into the lower levels. Neoliberal economic reforms have given way to an increasing trend in rent-seeking than before. And that is why the media is now talking of the increasing tendency towards crony capitalism.

Given our corrupt feudal past as well as a corrupt colonial bureaucracy, the bureaucratic system has institutionalised its own version of rent-seeking by small and big corruption in realms where there are opportunities for using their power.

Only a people’s movement will check the corruption and other forms of rent-seeking in the society. The parties that emerged out of such movements seems to have lost their credibility even before they got entrenched in the political system. But public action must continue through multiple ways and means. Public morality, personal integrity awnd honesty and ethical politics should not be consigned to academic studies and philosophical discourses. There is no short cut to public action.

ALSO READ: Anand Teltumbde: BJP’s Full-On Approach For 2024 Victory