Both nations are aggrieved by perceived humiliation at the hands of the West, and they are likewise led by two men who share values of nationalism, centralized power and autocratic governance. Furthermore, they hubristically think their countries’ future survival depends upon them….reports Asian Lite News

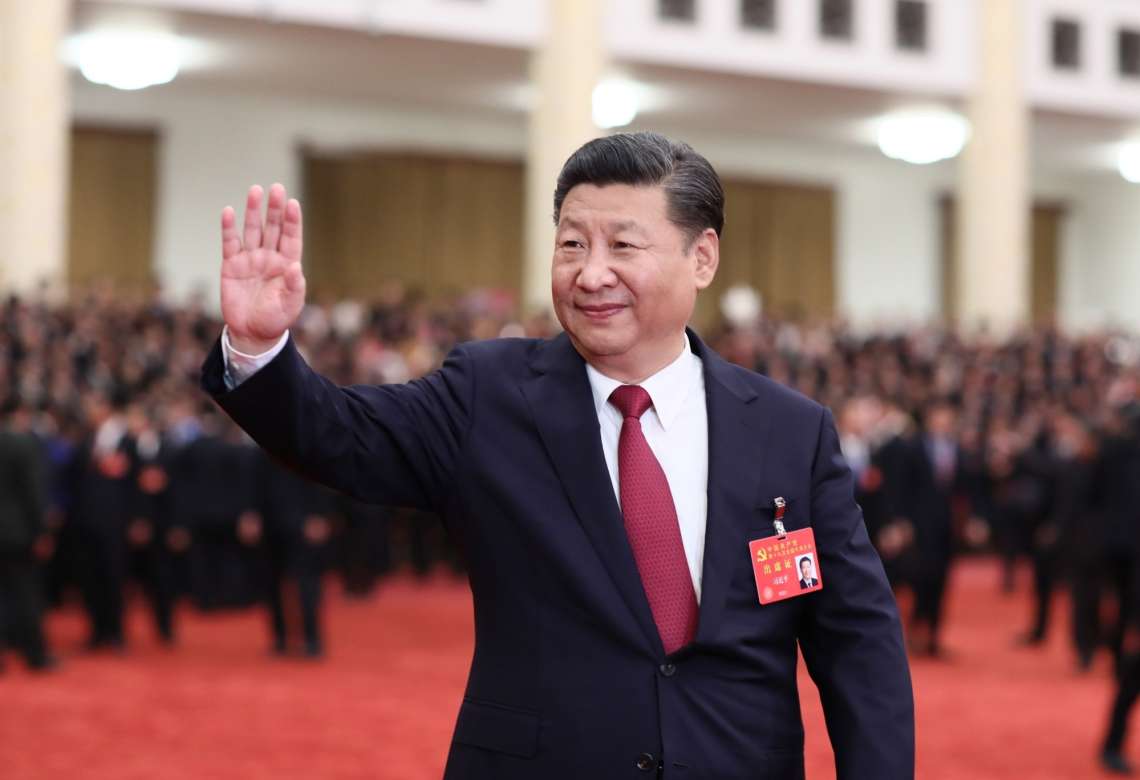

Although Chairman Xi Jinping has a personal affinity with President Vladimir Putin, the two countries’ bilateral relations are marked by reserve rather than trust.

Furthermore, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has proved rather awkward for China. Despite becoming bogged down in its “special military operation” that has now extended into its third year, Russia, the weaker partner in a bilateral relationship that is perhaps best described as a quasi-alliance, remains vital in China’s plans to build an axis against the US and Western allies.

Philipp Ivanov, Senior Fellow at the US-based Asia Society Policy Institute, said: “China and Russia are drawn to each other by virtue of their strategic geography, alignment of values and views of their current leaders, common enemy in Washington, natural economic complementarities and opportunism. Despite these areas of convergence, Russia and China are also driven apart by historical animosities, power asymmetry, competition in overlapping spheres of interest, deep cultural differences and shallow societal links.”

Both nations are aggrieved by perceived humiliation at the hands of the West, and they are likewise led by two men who share values of nationalism, centralized power and autocratic governance. Furthermore, they hubristically think their countries’ future survival depends upon them.

Yet the Ukraine war is the biggest test of Sino-Russian ties in the past few decades.

Putin’s military adventurism has both accelerated and disrupted bilateral ties, emphasizing to Beijing that Moscow is not a reliable partner.

Ivanov further wrote: “The war in Ukraine … has deepened Russia’s economic dependence on China, increased the power asymmetry between the two countries, and squeezed Moscow’s diplomatic playing field vis-a-vis China. Beijing has gained an even more loyal ally, as well as discounted access to Russian commodities, but its partnership with Moscow has damaged China’s ties with Europe and deepened the rift with the United States.”

In fact, Ivanov suggested that their relationship may have reached its zenith since both are fiercely independent and unwilling to compromise their strategic autonomy. “This, together with their growing power asymmetry and competition for spheres of interest, will limit the scope for further alignment. Yet, at this historic juncture, for both China and Russia, the benefits of their partnership offset the risks.”

Of course, China and Russia make perfect trading partners. The former is the world’s foremost supplier of manufactured goods, while Russia is rich in natural resources, meaning China can diversify its dependence on energy from the Middle East.

However, Ivanov argues the West is incorrectly overplaying the view that Russia has become a Chinese vassal.

A short time before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Xi and Putin met in Beijing, jointly declaring a strategic partnership “without limits”. Then, on the eve of the invasion, the PLA Daily declared: “The Sino-Russian relationship is in the best shape on record, and it has already become a great power relationship with the highest degree of mutual trust, cooperation, coordination and strategic value; the key to such a relationship is the strategic leadership of the leaders of the two states.”

Such an all-embracing declaration created a foreign-policy quagmire for China. The war put Beijing in a difficult position, as it was forced to side with Russia. Initially, Xi might have been invigorated by a swift Russian victory, for this would give him confidence to do the same against Taiwan. However, Ukraine’s staunch resistance has imposed a heavy cost on Russia, and made Xi realize that victory against Taiwan would not be as quick and tidy as he once imagined. Furthermore, international support for Ukraine surpassed anything Putin or Xi could have feared, and many were quick to impose sanctions on Russia. This is a key deterrent for China, since its economy relies upon international trade.

Guoguang Wu, Senior Fellow on Chinese Politics, Center for China Analysis at the same Asia Society Policy Institute, discerned three phases in China’s evolving policy over the Ukraine conflict. Xi has been forced to recalculate policies, and his miscalculations in his notion that the East is rising and the West is inexorably declining have been laid bare. Underwriting it all, he maintains the utmost priority on his own regime’s security, and his desire to challenge the Western-led world order.

The first policy stage, from February to May of 2022, according to Wu, was “friendship without limits”. China could not bring itself to call Russia’s military actions an invasion, and it has oft repeated Russia’s narrative that NATO must take primary responsibility for the war.

The second phase coincided with the stagnation of Putin’s offensive in Ukraine and his regime becoming odious to most of the world. After Putin’s blitzkrieg failed, China started to play down its “no limits” partnership with Russia. It detached itself from Russian actions, pretending to be a responsible peacemaker, and published a vague proposal for China-mediated peace talks in February 2023. Naturally, this was mere diplomatic deception, for China still condoned Russian aggression. Beijing claims to be “on the right side of history”, but it has actively undermined international solidarity in condemning Russia. One example is how Beijing lobbied Indonesia to exclude Ukraine as a topic at the G20 meeting in November 2022.

Xi was disappointed his “two-hands” policy was not accepted or applauded, ignorant that such a position only exposed Chinese hypocrisy and created growing disenchantment with Beijing. Russia, too, may have been annoyed by China’s public stance.

The third phase began around mid-2023, where China reaffirmed its alliance with Russia because Xi’s “two-hands” strategy of appeasing the West while supporting Putin did not work. Last year, for instance, Xi told Putin after a personal meeting,

“Right now there are changes [in the world], the likes of which we haven’t seen for 100 years, and we are the ones driving these changes together.”

Wu assessed: “China’s new policy, in my interpretation, is merely a revision of its initial stance on the war, reverting to clear support for Russian military action in Ukraine with less emphasis on diplomatic camouflage. However, the recalculation takes into account the reality that the West is still powerful enough to block Xi’s grand strategy.” Xi faces challenges on the home front with a more fragile Chinese economy, and he cannot afford Western-led sanctions that would exacerbate the situation.

Xi’s original dilemma remains, though. By supporting Putin, he upsets numerous other nations and risks bad press, sanctions and questions about his leadership. Yet he cannot abandon Putin, for that might accelerate defeat in Ukraine. The conflict has adversely affected China’s relations with the USA and Europe, at a time when it was trying to drive a wedge between the two. It has also undermined China’s narrative about respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of others.

If Putin loses in Ukraine, this would threaten his survival as Russia’s leader. Such uncertainty is not welcomed by Xi, who counts Putin a friend, plus a weakened and chaotic Russia does not help China at all.

Early on, the West threatened Beijing with severe repercussions if it supported Russia. It has not done so overtly, but it has provided ongoing support throughout the conflict.

Ivanov noted: “As far as we know, apart from limited transfers of dual-use equipment that can be used in Russia’s war effort, China has refrained from providing direct military aid to Russia. That might change if Russia faces a comprehensive defeat in Ukraine, which China may deem contrary to its interests. At this stage of the conflict, China sees the risks of Western sanctions and further damage to its vital relationship with Europe as outweighing the benefits of supporting Russia.”

In July 2023, the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) published a report detailing Chinese support for Russia. In 2022, Russian imports from China increased 13% to USD76 billion, while chip exports increased 19%, mostly through shell companies in Hong Kong. The ODNI stated that China “is providing some dual-use technology that Moscow’s military uses to continue the war in Ukraine, despite an international cordon of sanctions and export controls. The customs records show PRC state-owned defense companies shipping navigation equipment, jamming technology and fighter jet parts to sanctioned Russian government-owned defense companies.”

Other items documented as being sold to Russia are smokeless gunpowder, drones and spare parts, helmets and body armor.

Sino-Russian military ties include joint exercises, arms sales and military-technical cooperation. However, with Russia focused intently upon Ukraine, this has affected the regularity and depth of bilateral joint training.

China, too, would have watched with consternation the June 2023 rebellion by the Wagner private military contractor firm, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin. John Culver, Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Atlantic Council, said: “As Beijing watched Prigozhin’s private army move toward Moscow, one thought may have entered Xi Jinping’s head: ‘I was correct to jail Generals Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong and purge disloyalty and corruption from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).'” When Xi rose to power, the PLA was effectively a self-run entity, its top commanders having been appointed by Xi’s predecessors.

Culver elaborated: “As Xi rose in the Chinese Communist Party to be the designated heir by 2010, the party leadership watched in terror as the Arab Spring briefly swept autocrats from power, backed by the US/West. The lords of Zhongnanhai may have asked themselves, if the 1989 Tiananmen Square crisis happened here today, would the PLA again save the party? Or would the army – as the Egyptian military did – put its interests above its loyalty to the revolution? Looking at the corrupt military of that period, they likely concluded, ‘We don’t know. It probably would depend on the circumstances.’ For the party’s army, this is the wrong answer. Under Xi, party control over the PLA…has been greatly tightened. And lessons forgotten after 1989 were recalled, especially the need to move/replace general officers frequently and never again allow independent power bases to emerge in the PLA.”

It is patent that Putin’s actions in Ukraine have caused great discomfort to Xi, and also forced him to progressively alter his foreign policy. Given this, Wu suggested three elements in China’s ongoing policy. “First, Beijing will cease to try to significantly distance itself from Russia; but neither will China return to its ‘no limits’ partnership with the country. Instead, Beijing will cover its tracks while trying to reduce, if not entirely avoid, the costs of standing with Russia.

“Second, and most important, Xi’s revised calculations do not seem to be based on a Russian military triumph in Ukraine, but rather on Russia’s ability to fight for as long as possible. Xi might still expect that Putin could gain military advantage in Ukraine, especially if Western support for Ukraine begins to flag. In any case, a long war of attrition could have the effect of weakening both the West and Russia, thus making China the winner in both grand strategy and regime security.”

“Third,” Wu said, “China’s new policy will give it a bargaining chip in its growing rivalry with the West, particularly the United States. If necessary, Xi could leverage the shifting goals of the war, giving China more freedom for international manipulation.”

As Ivanov concluded: “The Russian war on Ukraine has dramatically raised the stakes. The war remains the most acute challenge to the international system, with profound consequences. One of them is how a Russian victory in Ukraine (defined by a larger territorial grab) would influence decision-making in Beijing on Taiwan. It is possible that as Xi ages, his power remains unchallenged, his fear of US encirclement grows and the Chinese economy slows down, he will be more willing to take risks to achieve reunification with Taiwan.” (ANI)

ALSO READ: