Despite its subscription to international treaties, China remains wary of disclosing the full extent of its arms sales and evidence suggests that Chinese equipment, including relatively modern products, often fails to meet the quality and reliability standards of Western equivalents….reports Asian Lite News

China is among the world’s top arms traders, with many sales achieved thanks to affordable products, Beijing’s political heft and favourable contractual terms. However, it is a case of buyer beware, because clients often end up with equipment that is defective or not well supported by their Chinese manufacturers.

According to the latest data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), eight Chinese companies – including AVIC, Norinco, China South Industry Group Corporation, China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC), China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC) – were among the world’s top hundred arms producers in 2022. Their combined revenue amounted to USD108 billion, a 2.7 per cent increase compared to the preceding year.

Notably, however, there was a 23 per cent decrease in the value of Chinese arms sales in the 2018-22 period compared to the preceding 2013-17 timeframe. Of course, it is impossible to point to the quality of Chinese equipment as the catalyst for this, but it should certainly be something that potential buyers keep in mind.

Nonetheless, both anecdotal and qualitative evidence suggests that purchasing from China comes with attendant risks. One prominent example is Jordan’s procurement of six CH-4B armed drones in 2016. Incredibly, after operating them for less than three years, Jordan promptly put its aircraft up for sale.

Chinese drones appear to have relatively high crash rates too. For instance, eight of 20 Iraqi CH-4Bs crashed within the first few years of operation, while the rest were grounded due to a lack of spare parts. In similar fashion, Algeria lost three CH-4Bs within a period of just months. Interestingly, other users of Chinese drones – such as Morocco, Nigeria and Turkmenistan – have moved on to Turkish-built aircraft instead.

The late Richard Bitzinger, in a report published by the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore late last year, posed the question: “What is the secret to success as an arms exporter? Repeat business. Countries buy arms from certain suppliers for specific reasons: performance, reliability, cost, alliance politics and so on. An important sign of success as an arms producer is building up a large and reliable overseas customer base – countries that return, year upon year, to buy additional weapons.”

Bitzinger continued: “Here is where China has always suffered as an arms exporter. True, it consistently accounts for around 5 per cent of the global arms transfer business …As it stands, China remains pretty much a niche player in the global arms market. It sells most of its weapons to a very small number of countries.” Indeed, in the past 20 years, more than 60 per cent of all Chinese arms sales went to just three nations: Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pakistan.

It is also noticeable that some countries who once bought significant quantities from China have ceased doing so. Examples include Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Sri Lanka and Turkey. “This begs the question,” Bitzinger mused, “if Chinese weapons systems are really that good, then why is their appeal so limited? Why is their traditional customer base still so small? In fact, one might infer from the large number of one-shot sales that most Chinese arms, while certainly better than what they used to be, are still no more than good enough, and that other foreign weapons systems – Western, Russian and Israeli – still outclass Chinese arms in most respects.”

The catalogue of dissatisfied customers is quite long. It is reported, for instance, that Bangladesh’s two Ming-class submarines acquired second-hand from China are unusable and unserviceable, while the country’s air force returned Chinese-built Y-12 and MA60 transport aircraft. Bangladesh also reported issues with K-8W trainer jets firing Chinese ammunition.

Likewise, Indonesia bought C-705 anti-ship missiles from China, but they persistently fail to hit targets in exercises. Another example is Nigeria’s procurement of F-7 fighters in 2009. Several were lost in crashes, while seven remaining airframes were returned to China for deeper maintenance in around 2020.

Myanmar procured 16 JF-17 fighters in 2016, but the junta has complained about structural and engine problems, as well as poor accuracy from their radar. In November 2022, media reported that Myanmar had grounded its JF-17 fleet, with its eleven delivered aircraft declared “unfit for operations”. Some customers are forced to turn to third countries to get the necessary support for their unreliable Chinese-made equipment, and thus Myanmar turned to Pakistani technicians to help rectify its JF-17 fleet.

It is not just aircraft that are problematic either. The Pakistan Navy procured four F-22P frigates, but Islamabad was soon reporting poor performance, degraded engines and other technical issues. The ships’ FM90N surface-to-air missile (SAM) system also proved ineffectual, and their IR17 infrared seekers had to be discarded because they could not lock onto targets. With Beijing uninterested in rectifying the frigates, Pakistan eventually turned to Turkey to upgrade them.

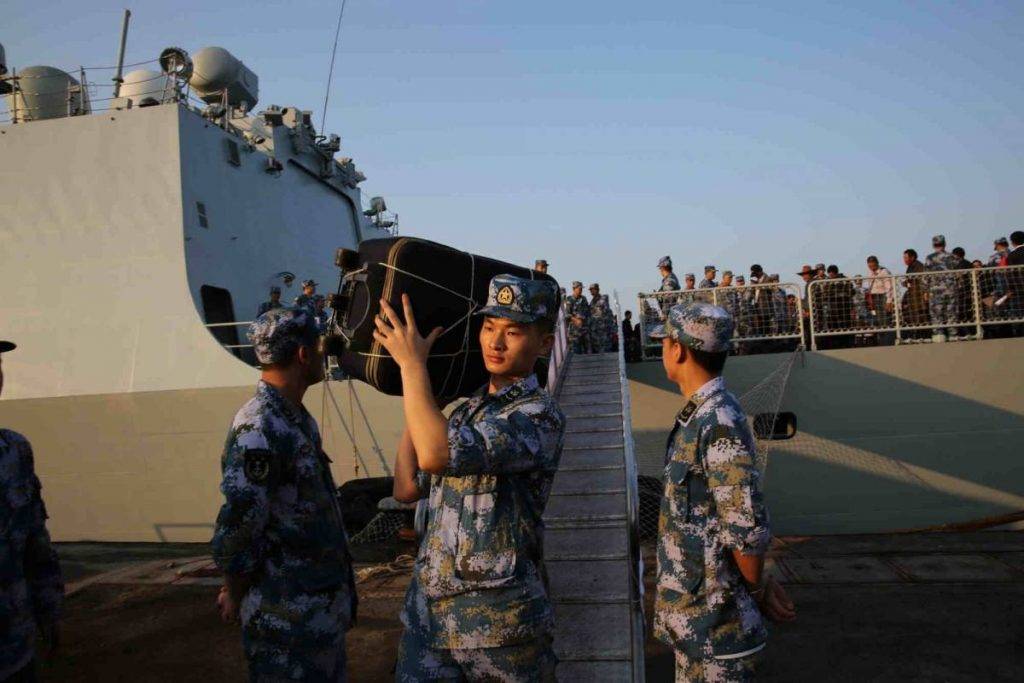

Furthermore, Chinese equipment is typically incompatible with Western systems, and this leads to further tribulations. For example, when the Royal Thai Navy received a Type 071E amphibious assault vessel from China last year, it was delivered without weapons, sensors or combat management system. Instead, Thailand will go to the lengthy and expensive task of inviting Western companies to retrofit the missing equipment. Similarly, Thailand turned to companies like Saab to retrofit radars and combat management systems in older Chinese-made frigates.

The Pentagon, in its 2023 report on the Chinese military, noted, “China is capable of producing ground weapon systems at or near world-class standards; although customers also cite persistent quality deficiencies with some exported equipment, inhibiting the PRC’s ability to expand its export markets.”

It added: “China is the fifth-largest arms supplier in the world…Many developing countries buy Chinese weapons systems because they are less expensive than other comparable systems. Although some potential customers consider arms made by the PRC to be of lower quality and reliability, many of China’s systems are offered with enticements such as donations and flexible payment options, which make them appealing options for buyers.”

Bitzinger concurred: “China’s strengths as an arms exporter remains, as it had for decades, at the low end of the business, offering basic equipment at rock-bottom prices with few strings attached. In particular, Beijing tries to dominate those types of armaments that could be considered ‘commodities’ – where cost, as opposed to technology or capability, is often the key determining factor. Examples include small arms, ammunition, artillery rounds and light armoured vehicles. China has also carvedut a particularly lucrative niche for itself in selling armed drones.”

contracts for new equipment, it can be frustrating for export customers attempting to gain aftermarket support from Chinese companies. There is little incentive for state-owned companies to provide timely support, because deals are done through the government and they do not stand to lose out commercially because of poor customer service. On the other hand, there is no questioning the ability of Chinese defence industry to churn out equipment quickly, or that its equipment is growing in technological sophistication.

Chinese arms sales are predominantly in developing countries in Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, Southeast Asia and, to a lesser extent, South America. It also gains sales from countries that do not wish to be reliant on the West. Indeed, Beijing is not particularly discerning as to who it sells to. It is happy to supply dictatorships such as Myanmar, with little regard as to how weapons are used against civilian populations or in nations with poor human rights records. The fact is, few strings are attached, especially if compared to the likes of the USA.

China is competing against Russia primarily, rather than American and European arms suppliers, and it is likely picking up customers as Russian manufacturers are kept occupied providing weapons and munitions to its own war machine in Ukraine. It will therefore be interesting to examine future data to see if this hypothesis is borne out.

China does not have treaty allies in the same way that the USA does with the likes of Australia, Japan or South Korea. Regardless, it uses arms sales to strengthen political connections and to whittle away at American influence. It is seeking to strengthen its soft power, and defence sales are one way of doing that, because it ties users to a state of dependency for the lifetime of that equipment.

The Pentagon pointed out: “China’s arms sales operate primarily through state-run export organisations such as AVIC and Norinco. Arms transfers also are a component of the PRC’s foreign policy, used in conjunction with other types of assistance to complement foreign policy initiatives undertaken as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.”

China transitioned from an administratively based arms export control system to one based in law in the early 2010s. Since then, it worked to reform its export control legislation to form one umbrella national-level legal and policy framework.

Eventually, the government implemented a new Export Control Law on 1 December 2020. The law supposedly follows three principles: ensuring exports are conducive to the legitimate self-defence capability of a recipient country; ensuring exports do not undermine peace, security and stability of the region concerned and the world as a whole; and non-interference in the internal affairs of the recipient.

Slightly earlier, on 4 October 2020, China joined the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT), which lists explicit international obligations concerning strategic trade control and which China must implement. At least on paper, China is legally obliged by the ATT not to transfer arms where they might be used to commit serious violations of international human rights, or where they could be diverted to proscribed users.

China still has a long way to go, though, and the Small Arms Trade Transparency Barometer in 2022 listed China as the eighth-worst arms exporter in terms of transparency. In that same list, Iran and North Korea formed the bottom two. Nor does China provide data to the United Nations Register of Conventional Arms.

Unfortunately, Chinese weapons are also reaching non-state actors in places like Africa, whether by weak oversight by purchasers or perhaps by direct complicity by Chinese sellers. For instance, Chinese weapons have been found in the hands of non-state actors in Darfur in Sudan, and in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

An August 2018 report from EXX Africa (now Pangea-Risk Insight) indicated that China was increasing its role in transferring arms to Africa. Purportedly, this was to protect infrastructure investments on the ccontinent, but the report concluded: “Following a new investigation that included collection of intelligence from well-placed security sector sources in the Horn of Africa, we have found evidence that Chinese weapons are making their way from the Chinese PLA support base in commercial port of Djibouti towards African conflict zones that have been placed under an arms embargo.” EXX Africa also reported shipments of heavier equipment such as WS-1 multiple rocket launchers, HJ-8 anti-tank missiles and tank ammunition flowing through Djibouti.

A report issued by the French Ministry of Defence in 2021, authored by Bernardo Mariani, found likewise: “Chinese arms manufacturers have made inroads on the continent. During the 2016-20 period, China was the second-biggest supplier of arms to sub-Saharan Africa. Weapons and ammunition of Chinese origin are in the hands of a range of actors, including non-state forces, operating in a number of countries. These are in many cases a result of diversion.”

Despite subscribing to international treaties, China remains paranoid about revealing the true extent of its arms sales. There is also ample evidence that Chinese equipment, even relatively modern products, do not attain to the quality and reliability levels of their Western equivalents.

Then again, some countries simply prefer to buy cheaper products with the advantage of knowing they will not be asked embarrassing questions by the Chinese authorities. (ANI)

ALSO READ: Labour Unrest Soars Amid China’s Slowdown