China’s rise as a global leader in shipbuilding is undeniable. With a 53.4% share of global shipbuilding orders by deadweight tonnage in 2024, Beijing has outpaced rivals like South Korea and Japan, producing more ships annually than any other nation, writes Commodore (Dr) Johnson Odakkal (Retd)

China’s rise is no accident. Strategic industrial policies “Made in China 2025” and the 14th Five-Year Plan have injected subsidies and favourable financing into dual-use shipyards like Jiangnan, Dalian, and Hudong-Zhonghua. These yards churn out advanced platforms from the 80,000-ton Fujian aircraft carrier, nearing commissioning in 2025, to the Type 055 Renhai-class destroyers, equipped with 112 vertical launch cells rivalling U.S. cruisers. The PLAN’s expansion supports China’s blue-water ambitions, enabling power projection from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean, increasingly integrated into the Belt and Road Initiative’s maritime corridors.

But the tide is not entirely in China’s favour.

Rising wages and an ageing workforce have triggered labour shortages, particularly in complex naval programs. In 2024, reports from the Wuchang Shipyard revealed delays in Type 039A Yuan-class submarines, with shipyard managers struggling to fill skilled engineering roles. In high-end segments like LNG tankers and cruise ships, China continues to trail South Korea and European shipyards, whose competitive edge lies in precision engineering and post-sale support.

Quality control issues have further raised red flags. A mid-2024 mishap during the construction of a nuclear-powered submarine at Wuhan’s Wuchang Shipyard resulted in the vessel sinking at dock, highlighting deficiencies in material standards and oversight. Although downplayed by Chinese authorities, satellite imagery confirmed long delays in the PLAN’s submarine modernisation. Similar concerns surfaced with Type 055 destroyers, one of which was forced to abort deployment due to propulsion failure, suggesting that quantity may be masking vulnerability.

Technological ambition, too, is tempered by operational reality. China’s much-touted DF-21D “carrier killer” missiles remain untested in real-world scenarios. Western analysts question their efficacy against U.S. countermeasures, noting that hype has often outpaced validation in China’s arsenal. In contested spaces like the Taiwan Strait, capability gaps in live targeting, electronic warfare resilience, and joint command could constrain China’s reach.

A critical front for China’s naval diplomacy, defence exports, has yielded mixed outcomes. Smaller Indo-Pacific states drawn to China’s lower-cost naval offerings are increasingly cautious. Bangladesh’s 2017 acquisition of two Ming-class submarines, for instance, revealed dated technology and maintenance woes. Sri Lanka’s P625 frigate, gifted in 2019, suffered repeated breakdowns and was sidelined for long repairs, exposing poor build quality. In 2022, Thailand cancelled its Yuan-class submarine deal after Germany refused to supply propulsion systems, revealing China’s continued reliance on foreign technologies.

Pakistan, China’s closest defence partner, embodies the challenges of dependency. Its Type 054A frigates, while sophisticated on paper, lack interoperability with Western systems and require sustained Chinese technical assistance for maintenance. This dependency extends beyond hardware; Pakistan’s naval autonomy is constrained by the opacity of Chinese logistics and spares support. Algeria’s experience with Chinese corvettes, marred by malfunctioning sensors and weaponry, reinforces the narrative: China may be an affordable exporter, but not yet a reliable one.

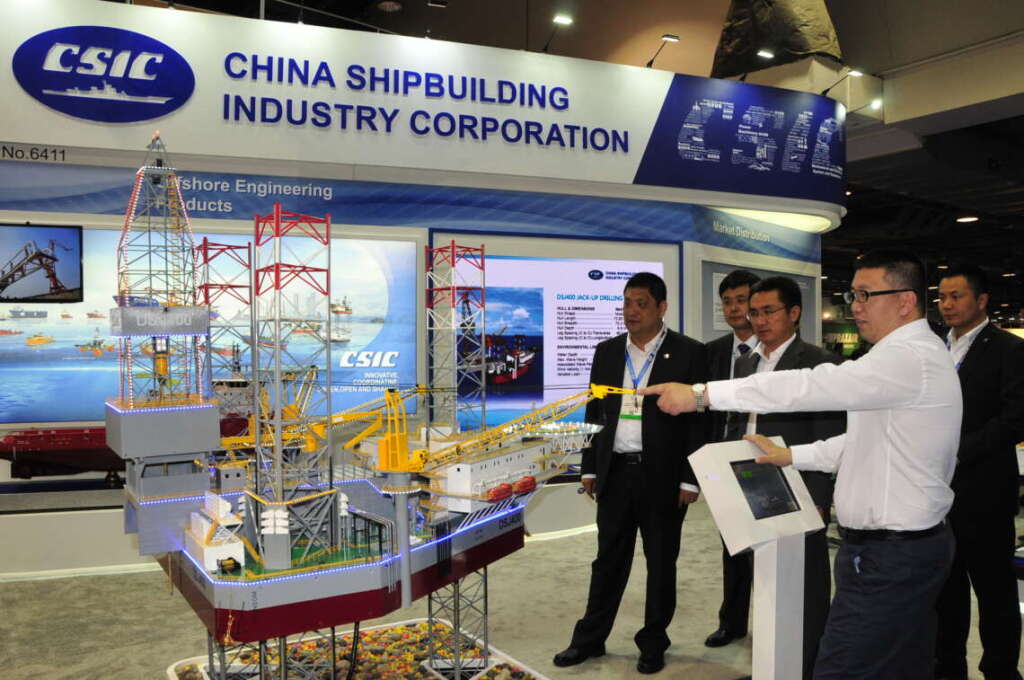

Ironically, these weaknesses coexist with China’s overwhelming shipbuilding scale. The China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) launched 39 warships between 2019 and 2023, surpassing the entire tonnage of the British Royal Navy. Jiangnan Shipyard alone matches the capacity of all U.S. naval shipyards combined. In any future conflict, this industrial advantage could allow Beijing to replace and repair losses far faster than its adversaries, a stark asymmetry in warfighting sustainability.

Yet, a navy is not just steel, it is strategy, systems, and sailors.

Corruption, dual-command structures, and political indoctrination weigh down the PLAN’s operational effectiveness. Key challenges remain in mastering nuclear propulsion, advanced antisubmarine warfare, and expeditionary sustainment. Additionally, the youth recruitment crisis facing the People’s Liberation Army due to declining faith in the Communist Party narrative threatens long-term naval human capital.

For regional powers, the message is sobering. The U.S. Navy, meanwhile, is projected to drop from 296 ships in 2024 to 294 by 2030, hobbled by budgetary constraints and shipyard limitations. Alliances like Quad and AUKUS must move from rhetoric to capacity-building, joint shipbuilding, advanced logistics hubs, and a shared operational picture are vital to preserve regional stability.

China’s shipbuilding growth is real but not unassailable. Its strengths, scale, central planning, and political will, have produced a formidable navy. Yet its weaknesses, technical reliability, human capital, and export credibility remain significant. As Xi Jinping’s vision of a “world-class military” sails into deeper waters, the question is whether the PLAN can navigate through its own structural turbulence.

For Indo-Pacific nations and global democracies, the course is clear: reinvest in maritime capabilities, exploit China’s strategic overreach, and anchor partnerships that uphold a rules-based order.

(Commodore (Dr.) Johnson Odakkal is a maritime scholar, strategic affairs analyst, and Indian Navy veteran. He serves as Faculty of Global Politics and Theory of Knowledge at Aditya Birla World Academy, Mumbai, and Adjunct Faculty of Maritime and Strategic Studies at Naval War College, Goa.)