The Kunming gathering appears to mark the beginning of a dangerous geopolitical maneuver. Behind the diplomatic curtain, efforts to forge a strategic bloc seem to be underway—one that not only threatens regional stability but also risks compromising Bangladesh’s hard-earned strategic autonomy, writes Dr. Anjuman A. Islam

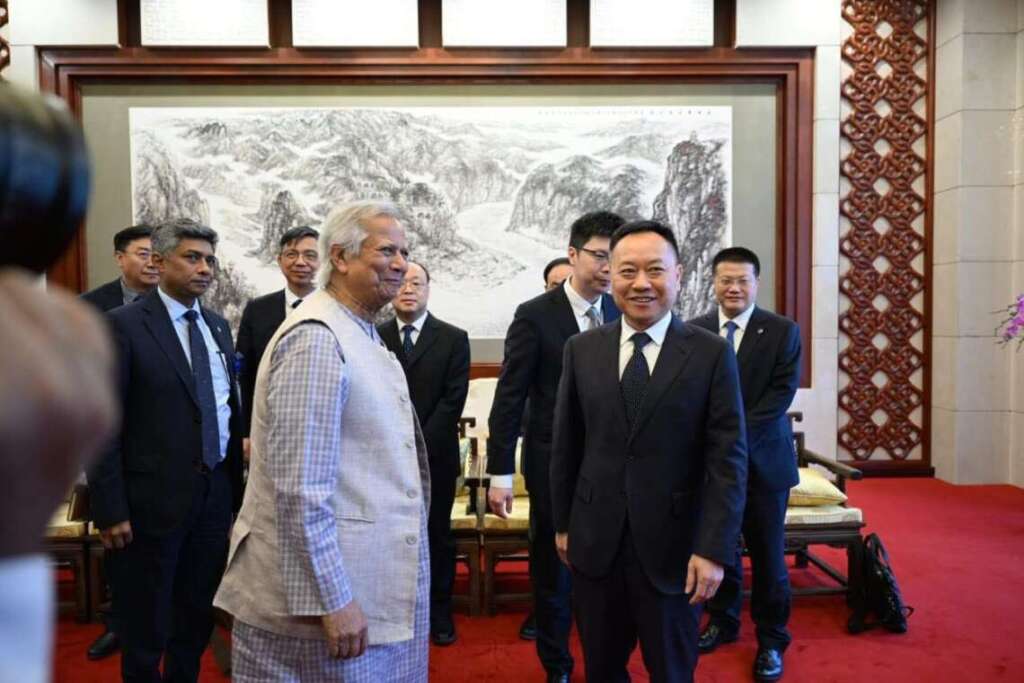

Projected as diplomatic triumph by Pakistan and China, the sudden and recently held trilateral meeting in June with attendance of government representatives from China, Pakistan, and Bangladesh in Kunming has triggered concerns across South Asia’s diplomatic landscape. Bangladesh’s Foreign Affairs Adviser, M. Touhid Hossain, was quick to label the Kunming meeting a non-political and informal one, downplaying any emerging alliances.

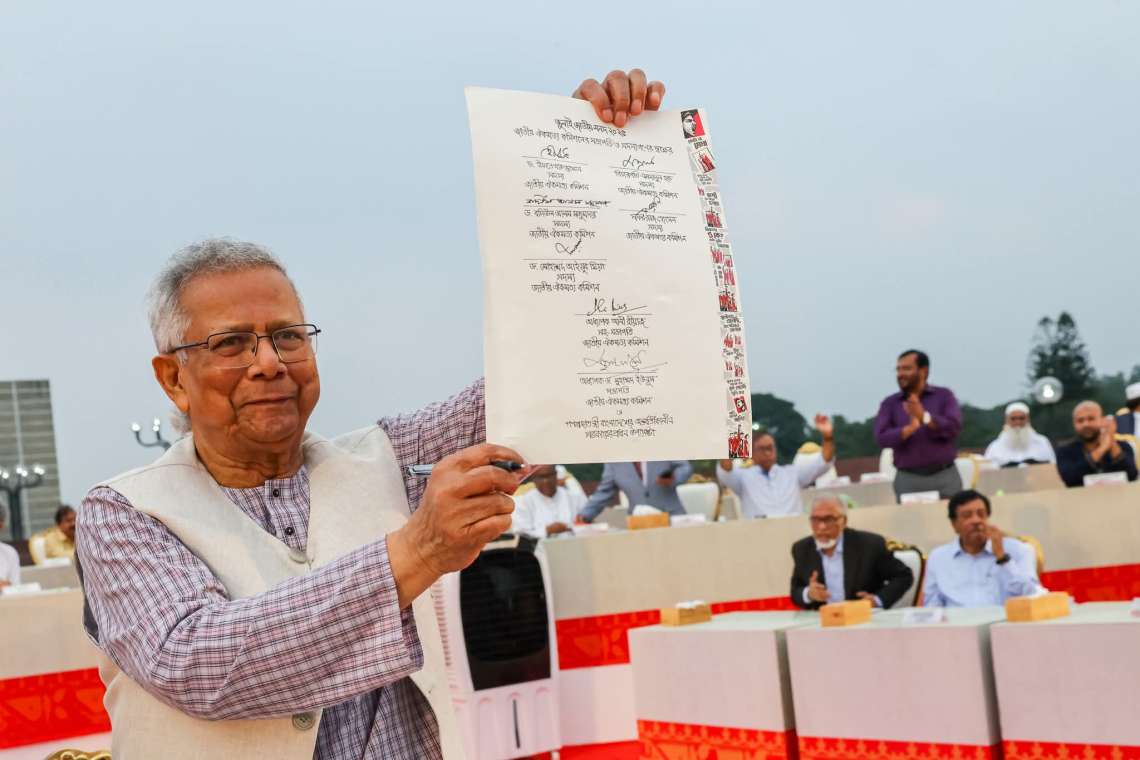

But the denial of any alliance fell flat in light of a series of events that took place in the run up to the Kunming meeting rather triggers alarm given the historic context of state backed cross border terrorism to stoke instability in South Asia, reportedly by Pakistan- China axis. Importantly, months earlier, a high-level Pakistan delegation visited Bangladesh to reinvigorate ties under the watch of unelected interim government led by noble laureate Dr Muhammad Yunus. Not to mention, in March, Yunus, during a visit to China, in a veiled threat to India’s northeastern states, appealed to China to “extend” in the region. On top of that, Pakistan Army’s decades of persistent denial to whitewash one of the brutal war crimes including genocide inflicted on millions to stop the birth of Bangladesh must be taken into account.

Counting on these diplomatic maneuvers, the Kunming gathering appears to mark the beginning of a dangerous geopolitical maneuver. Behind the diplomatic curtain, efforts to forge a strategic bloc seem to be underway—one that not only threatens regional stability but also risks compromising Bangladesh’s hard-earned strategic autonomy.

No wonder for China, Bangladesh is the gateway to the Bay of Bengal and a counterbalance to Indian influence. With Pakistan, China already holds considerable clout. Contrary to popular belief, China and Pakistan do not form a monolithic alliance. Beneath the surface of their so-called “iron brotherhood” lies a web of internal tensions and deep-rooted mistrust. Within Pakistan, Chinese-led projects like the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) turned into a new source of conflict due to opaque plans and further neglect of locals. Many accuse Islamabad and Beijing of plundering local resources, bypassing indigenous communities, and laundering the proceeds into foreign accounts.

Despite its internal discontent, Pakistan now seems eager to pull Bangladesh into this web, not out of goodwill, but to serve Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions and shore up its own weakening strategic posture. In absence of an elected government in Bangladesh, China appears to have been aggressively pursuing its goal of exploiting the youngest nation in South Asia to advance its strategic ambition.

In his social media post, Bangladesh economist Selim Raihan summed the move as an autocratic one in nature on part of the Yunus led regime and questioned about the lack of mandate and transparency before getting entangled with the project, cited in a BBC Bangla report, pointing out inevitable danger towards Bangladesh behind such sudden diplomatic engagement

Pakistan’s Vested Interests in CPEC

It appears at the heart of Pakistan’s interest in the trilateral framework lies the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the centerpiece of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in South Asia. Pakistan hopes to revive and reinvigorate CPEC by bringing Bangladesh into its fold, projecting the illusion of a growing regional consensus around Chinese-led development.

But citizens in Pakistan, CPEC has turned in to a hated symbol of deprivation. In fact, it is a source of considerable domestic contention. Balochistan, one of the primary routes for CPEC, remains a flashpoint Local communities accuse both Islamabad and Beijing of pillaging their natural resources while offering little in return. Discontent over forced displacement, environmental degradation, and lack of employment opportunities for locals has turned many Baloch citizens against the initiative altogether.

In Sindh, CPEC has been criticized for skewing development toward Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, while in Gilgit-Baltistan, it has heightened fears of demographic manipulation. Political parties including Awami National Party (ANP), factions of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), and the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) have called for greater transparency and local ownership of the projects, emphasizing how the benefits have disproportionately gone to the military and elite, depriving locals.

Moreover, Pakistan’s growing economic reliance on China has triggered fears of a looming debt trap. Assets like Gwadar Port, are now perceived as representations of dependency. In marketplaces, resentment simmers as Chinese goods displace local industries and Chinese laborers replace Pakistani workers.

China Pakistan Tango

These internal frictions underscore a crucial reality: Pakistan and China are not guided by principles. Nowhere is this dissonance more apparent than in Pakistan’s deafening silence on China’s repression of Uyghur Muslims. This silence testifies to Pakistan’s economic dependence and diplomatic vulnerability. It is through this uneasy and fractured alliance that China now seeks to extend its influence toward Bangladesh.

China’s Backdoor Entry

By involving Pakistan in this trilateral arrangement, Beijing seeks to use its client state as a diplomatic intermediary to soften Dhaka’s hesitations. But the Bangladeshi government’s reception of this overture has been far from enthusiastic.

In the Kunming meeting Bangladesh did not sign the joint press release and rejected the formation of a Joint Working Group (JWG), citing lack of clarity and transparency. Yet even by attending, Dhaka inadvertently legitimized an initiative that could evolve into a new regional bloc designed to undermine India and establish China’s dominance in South Asia. Not to mention, during his recent China visit, Yunus called Bangladesh the “only guardian of the ocean” for India’s landlocked north-east and suggested that the region could become an “extension of the Chinese economy.” This statement clearly acted as a shot in the arm for the Chinese gamble targeting Bangladesh.

Pakistan’s consistent betrayal

A recent BBC Bangla report unmasked the double standard and continuation of reliance on treachery and deception by Pakistan regime with people of Bangladesh. Following the high profile visit of Pakistan government representatives to Dhaka led by Pakistan Foreign Secretary Amna Baloch in April, Pakistan government did not tender apology for the 1971 war crimes despite pressed by her Bangladesh counterpart. The legacy of liberation war has been a source of pride and inspiration for Bangladesh yet the systematic denial of war crimes by Pak army emerged the biggest roadblock.

But the biggest blow came when Pak Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif claimed they have avenged the defeat of 1971 during the standoff with India in May, a sheer disregard and undermining of the supreme millions of Bangladeshis killed, raped, tortured and displaced at the hands of Pakistan armed forces, aided by its proxy Jamaat e Islami. As a strong ally of Yunus regime, Jamaat has now spreading tentacles to solidify countrywide political clout. Ranked as third most non state armed outfit Islami Chhtra Shibir, the student arm of Jamaat, sent its top leaders to Pakistan recently and a meeting took place with the student arm of Jamaat -e Islami Pakistan, a move described as a betrayal with Bangladeshi students by student fronts of other political parties.

Terror and deceit

After August 5, Syed Maroof Pakistan High Commissioner to Bangladesh, became one of the most active diplomat in terms of social media activities and public engagement, mostly with pro Yunus regime. Yet within less than a year, the envoy took a quiet and abrupt departure on May 11 from Bangladesh without even attending any farewell curtesy calls with policymakers. According to media reports, the envoy stood accused of moral turpitude as caught red handed in immoral relationship with Bangladesh women.

To cover up the exit, Pakistan High Commission only informed Bangladesh that the diplomat has went on two weeks leave, reads Prothom Alo report. But weeks later Pak foreign ministry announced a new ambassador to Bangladesh. However this disgraceful saga is not an isolated one. In a statement issued in September 2024, US based Lemkin Institute of Genocide added “the current political instability in Bangladesh is directly related to the events of the 1971 genocide and its aftermath.

The statement further exposed targeting of the country’s judiciary, and specifically the International Crimes Tribunal (ICTB) that tried perpetrators of the 1971 genocide and arbitrary arrests of “judges, prosecutors, human rights workers, journalists and others involved in the ICTB process in retribution for their past participation in a genocidal accountability process”. Over five decades since the birth of Bangladesh following public surrender by Pak armed forces on December 16, 1971, a litany of efforts reportedly orchestrated by Pakistan establishment to destabilise Bangladesh. Past reports by a number of western outlets including Time Magazine, NY Times showed how Pakistan’s Interservice Intelligence (ISI) agency sent militants in Bangladesh with all out support for aiming for an Islamic revolution in Bangladesh and India, in sync with its denial of war crimes. The ten truck arms seizure, largest in Bangladesh’s history back in 2004, testifies to ISI’s record of dragging Bangladesh into cross border terrorism by supporting Indian separatists including leaders from the United Liberation Front for Assam (ULFA). In 2015, Mohammad Mazhar Khan, attaché at the consular section of Pakistan high commission in Dhaka, also an undercover ISI agent, reportedly found involved in terror financing and currency forgery racket.

The Vacuum in Bangladesh

What makes the current situation in Bangladesh even more perilous is the troubling political vacuum at home. The Yunus-led interim government lacks the legitimacy to make far-reaching foreign policy decisions. Yet, it has embarked on high-stakes diplomacy that could redefine Bangladesh’s geopolitical orientation for years to come. This is not merely reckless—it is undemocratic. The absence of parliamentary debate, national consultation, or even public discourse around the Kunming trilateral meeting is not just a procedural oversight—it marks a serious democratic failure. On part of Bangladesh, the decision-making process has been opaque, top-down, and disconnected from the will of the people, causing grave concerns about transparency, accountability, and national interest.

The confusion within the foreign ministry and the subsequent diplomatic fallout from the meeting reveal just how unprepared and unauthorized this regime is to steer Bangladesh’s foreign relations. A nation that once prided itself on balancing relationships with India, China, the West, and multilateral institutions is now at risk of being portrayed as indecisive, vulnerable, and easily swayed. Without an elected government accountable to its people, foreign engagements—especially those involving authoritarian regimes—should be approached with utmost caution. Anything less undermines Bangladesh’s sovereignty, credibility, and the spirit of democratic governance.

Strategic Drift and Regional Risk

The emerging trilateral arrangement comes at a particularly sensitive moment in South Asian geopolitics. It coincides with a period of subtle recalibration in India-Bangladesh relations. While diplomatic friction may exist, choosing this moment to gravitate toward Beijing and Islamabad is not strategic foresight—it is a grave misjudgment. India, despite occasional political tensions, has historically proven to be a consistent and reliable partner. It stood by Bangladesh during its liberation war, extended cooperation in power and trade, and unlike China, has not entangled Dhaka in opaque loan agreements or extractive infrastructure projects masked as “development.”

India’s vision for regionalism is built on transparency, mutual respect, and shared prosperity. Regional initiatives such as BBIN (Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal) and BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation) are aimed at fostering inclusive growth and connectivity across South and Southeast Asia. These are frameworks that empower countries rather than subjugate them.

n stark contrast, the China-Pakistan model follows a blueprint of coercive economics and strategic encirclement. From CPEC to military cooperation, their model thrives on debt dependency and geopolitical leverage. Bangladesh must recognize that entering such a sphere of influence could endanger its economic sovereignty and regional credibility.

Strategic Clarity, Not Diplomatic Confusion

Bangladesh stands at a crucial juncture where its foreign policy choices must reflect the will of its people, not the opportunism of external powers or the whims of an unelected government.

To prevent further erosion of strategic clarity, Bangladesh must restore coherence in its foreign policy. This starts with a return to democratic governance. Only an elected government, accountable to the people, should have the mandate to shape the nation’s alliances and regional posture. Foreign policy decisions must also be brought into the public domain. They should be openly debated in parliament, scrutinized by civil society, and reported on by a free and independent press. The current culture of secrecy and backroom dealings must end if Bangladesh is to maintain its integrity on the world stage.

At the same time, Dhaka must recalibrate its strategic orientation. Relations with India—despite occasional tensions—remain vital for regional stability and economic cooperation. The stakes are too high for missteps. Bangladesh must act with clarity, transparency, and purpose—before diplomatic confusion becomes strategic failure.

Say No to Serfdom, Say Yes to Sovereignty

The Yunus administration’s quiet dance with China and Pakistan is not just diplomatically risky—it is existentially dangerous. If allowed to continue, it could bind Bangladesh into an exploitative framework that erodes its sovereignty, undermines regional stability, and alienates historic partners.

Bangladesh has earned its place on the world stage through struggle, sacrifice, and success. It must now defend that legacy—not surrender it for short-term optics and long-term bondage. The message from Kunming is clear: strategic serfdom is knocking. Bangladesh must not open the door.