If China wants foreigners to continue investing, it needs a certain degree of transparency. That is the fine line that Beijing is trying to straddle since it cannot have it both ways…reports Asian Lite News

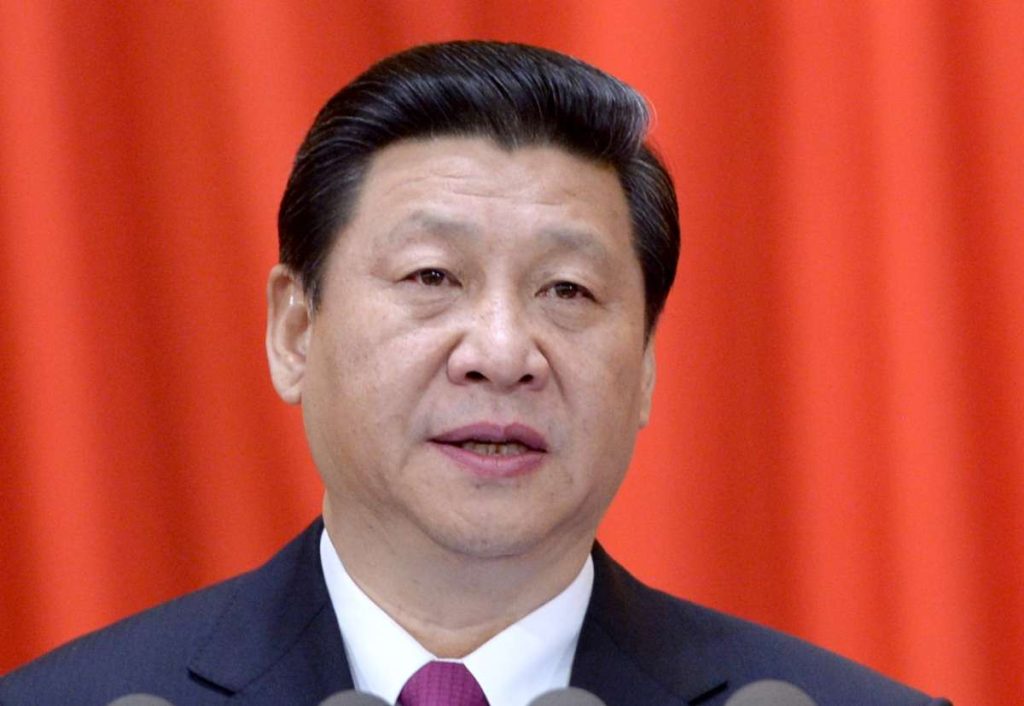

For a decade, it seemed Chairman Xi Jinping could do no wrong. Media controlled by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) praised this demigod whose face and sage wisdom graced front pages nationwide.

However, as economic and strategic realities resulting from Xi’s policies begin to bite, the people of China are now paying the price.

Authoritarian regimes must carefully control information, and China is extremely good at this. Yet, to ward off criticisms at home and abroad, Beijing has taken more severe steps to reduce the flow of data harmful to the CCP. Thus, in August the National Bureau of Statistics of China stopped releasing data on youth unemployment.

June’s data was alarming, with unemployment amongst 16-24-year-olds reaching 21.3 per cent, double what it was four years ago. However, the situation is far worse than these figures denote, for in China a person is considered gainfully employed even if they work only one hour per week! Nor does this figure include young people in rural areas.

Some believe China’s actual youth unemployment rate could be as high as 50 per cent. The National Bureau of Statistics is a magical government department – for it can produce all manner of manipulated data – but there is a limit to the deception even it can release. Simply by stopping the publication of embarrassing information, the CCP hopes the problem might disappear.

In fact, this government department has been steadily publishing fewer economic indicators in recent years as the data becomes more damning. Truth and transparency have never been central tenets of any communism regime, in China particularly so.

The best Xi can offer China’s youth are empty epithets such as “endure hardships” and “eat bitterness”. After all, this is what Xi did when his prominent political father Xi Zhongxun was “sent down” as punishment, and he had to work on a farm in Shaanxi.

However, he himself did not enjoy eating bitterness, for he fled back to Beijing. He was recaptured and eventually spent seven years working in a village. Yet, such injunctions from powerful, out-of-touch political figures do not sit well with China’s advantaged generations who have never known leanness.

In June, year-on-year exports slumped 12.4 per cent. Households are laden by debt, and household consumption makes up just 40 per cent of China’s GDP. The CCP wants multinationals to boost Chinese investment, but at the same time it wants greater control of intellectual property and access to data.

Yet if China wants foreigners to continue investing, it needs a certain degree of transparency. That is the fine line that Beijing is trying to straddle since it cannot have it both ways.

China is now descending into paranoia, something accelerated by the recent introduction of the Anti-Espionage Law. Citizens are urged to uncover foreign spies, especially among those Chinese who regularly mix with foreigners. Such an atmosphere of xenophobic national security will presumably turn into a witch hunt, with rewards of up to RMB100,000 on offer for solid tipoffs about spies.

Another worrying indicator is China’s fertility rate. In 2022 the fertility rate dropped to a record low of 1.09, whereas a rate of 2.1 is needed to sustain a population. China’s fertility rate is among the world’s lowest, alongside the likes of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

Last year, China’s population dropped for the first time in six decades, and this year India surpassed China to become the world’s most populous nation. As its population rapidly ages, this will have dramatic impacts on China’s future economic growth.

China’s old-age dependency ratio (the ratio of people aged 65+ to those aged 15-64) is predicted to reach nearly 52 per cent by mid-century. This means that, for every two working-age individuals, there will be one person aged 65+. By the 2080s, that figure could climb to almost 90 per cent.

The number of retirees will skyrocket, reducing China’s workforce and putting pressure on the country’s social safety net and healthcare. This is all exacerbated by China’s very low net immigration rate, with just 0.1 per cent of its population made up of immigrants.

According to the US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies: “After peaking at over 1.42 billion in 2021, current forecasts project that China’s population will shrink by over 100 million people by 2050. By the end of the century, China’s population may dwindle to less than 800 million, with more dire scenarios putting the figure at less than 500 million.”

The nation’s one-child policy was introduced in 1980, leading to forced abortions and sterilization. In 2016 this was raised to two children, and last year it began encouraging three-child families.

As the man with answers to every problem, Xi chaired a meeting on the topic in May. However, even he will have a hard time overcoming traditional stereotypes and institutional gender discrimination.

While Chinese data lacks credibility, it still gives a helpful sense of trends. At the moment, most of these trends are alarmingly negative.

Indeed, President Joe Biden described China’s economy as a “ticking time bomb”, and another indicator of that is a housing slump. Recent figures showed that house prices for existing dwellings have slumped 6 per cent since August 2021. In prime neighbourhoods such as Shanghai and Shenzhen, the downward trend is even more extreme with drops of at least 15 per cent.

On 17 August, the China Evergrande Group sought Chapter 15 bankruptcy protection in New York. This move was to protect US assets from creditors while it works on restructuring deals. Evergrande has approximately USD330 billion in liabilities, and it posted USD81 billion in losses for 2021-22.

When giant housing developers are mired in financial difficulties, the risk of contagion is tangible. Since mid-2021, companies accounting for 40 per cent of Chinese home sales have defaulted, and thousands of incomplete homes dot China’s cities. Country Garden, China’s largest private house developer, is also in difficulties after it failed to meet recent interest payments.

After a recent trip to China, Taisu Zhang, a Professor of Law at Yale Law School, noted that “the overwhelming and obvious impression was one of negative economic sentiments, even pessimism, across the board: tentative spending on behalf of consumers, lack of confidence on behalf of entrepreneurs and investors, general miasma in the financial and legal services sectors, all responding to a perceived lack of fiscal and institutional commitments in government policy, despite positive pro-economy rhetoric being issued for over half a year now.”

Zhang continued: “The general impression among academic observers, which I share, is that the central government still has quite a bit of unused policy firepower (stimulus of all kinds, various institutional commitments it could issue to the tech and real estate sectors, etc.), but has thus far been somewhat hesitant to put its money where its mouth is, literally and figuratively speaking, and private economic sentiments are unlikely to improve until it does. Local governments are fiscally exhausted by this point, and cannot do much on their own.”

The professor continued: “Negative sentiments are, of course, self-reinforcing if not quickly reversed through decisive policy action or external shocks, and therein lies the biggest short-to-medium threat to the Chinese economy. There are, of course, powerful sociopolitical reasons (and also long-term moral-hazard considerations) for why the central government has been somewhat hesitant to fully jump in, but time seems to be running short before social sentiments sour in a more permanent way.

“All in all, while the actual economy is undeniably livelier than it was last year (and how could it not be, given the comparison set?), subjective sentiments seem much worse. It was still possible, even last July, for some to write off economic headwinds as situational to the pandemic, but now the pandemic is over and the long-term problems that academics have been harping about for years – demographics, local government finances, real estate bubbles, low consumption, etc. – are no longer avoidable, regardless of one’s socioeconomic position. The amount of governmental action (and money) needed to arrest this slide into systemic pessimism seems quite enormous.”

Amidst all this gloom, one bright spot came from Chinese customs data. It showed trade with Russia for the first half of 2023 had grown a staggering 40.6 per cent to USD114.55 billion, including a dramatic 78.1 per cent increase in imports of commodities like oil and gas.

Xi has taken responsibility for running every aspect of Chinese life. As things go wrong, it seems impossible that he should not be tarnished, despite the nation’s massive propaganda organ.

Indeed, what are Xi’s qualifications for greatness? He studied chemical engineering from 1975-79, and Marxist theory and ideological education from 1998 to 2002. However, he has no formal training in such matters as public policy or economics. Despite this, he views himself as an expert in absolutely every topic imaginable.

Since assuming the leadership of China, Xi has amazingly found the time to publish eleven books on subjects such as governance, economic development and foreign policy. Ironically, his latest tome published in late July was entitled On Studying and Implementing the Important Discourses on the Management of Water Resources.

This was immediately before Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei suffered the most severe flooding in 140 years. In Hebei Province alone, a million people were displaced, with the situation exacerbated by authorities lifting floodgates in reservoirs and spillways to alleviate the risk of flooding in Beijing and Tianjin.

Ni Yuefeng, Party Secretary of Hebei, was excoriated for promising to do everything to reduce “the pressure on Beijing’s flood control and [to] resolutely build a ‘moat’ for the capital”. Nor did Xi show any interest in visiting the flood-ravaged regions, for he was in Beidaihe with other Politburo members and advisors.

There is certainly a sense that Xi’s luster is wearing off, a process that accelerated with his strict imposition of lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, and then his sudden reversal. Floods and COVID have confirmed that Xi is not really interested in the average Chinese citizen, for he is preoccupied with “governing” and building his legacy.

In an article for The Jamestown Foundation think-tank, Professor Willy Wo-Lap Lam assessed: “After emerging as China’s ‘leader for life’ and filling top party organs such as the CCP Central Committee and the Politburo with members of his own faction, paramount leader Xi Jinping has been relentlessly buffeted by what he refers to as ‘high waves and dangerous winds’ in his effort to keep the ship of state afloat.

However, whether the supreme leader and his newly minted Politburo can acquit themselves of handling these challenges remains dubious.”

Other matters to underscore Xi’s fallibility were the disappearance of Foreign Minister Qin Gang, and the two top leaders of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) in charge of China’s nuclear arsenal. Qin was replaced by old-timer Wang Yi, while PLA Navy and Air Force officers were shifted to lead the PLARF. All those implicated in these scandals were hand-selected by Xi, so it seems he is not such a good judge of character.

The new commander and political commissar of the PLARF might be loyal to Xi, but they likely know little about nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles. Then again, Xi has routinely demanded political fealty as a top quality in candidates, and this seems to have trumped professional knowledge.

Xi is good at laying out grandiose schemes such as the Belt and Road Initiative, and promulgating the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. Yet most of the time nobody can initially even explain what these schemes entail, and it is left for underlings to bring form and meaning to them.

Xi seems not so good at the nitty-gritty of detailed governance, and yet he is the one who sits on every committee and has an apparently infallible opinion on everything.

Xi’s case is not helped, Professor Willy Lam explained, by “serious administrative overlap and lack of clear-cut differentiation between the functions of party and government”.

The State Council and Prime Minister Li Qiang are undercut by the CCP Central Finance and Economic Commission, the Central Finance Work and CCP Central Commission for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, for instance.

There are also testy relations between the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the CCP’s Central Commission for Foreign Affairs.

Lam concluded: “Given unmistakable signs that China’s economy had failed to return to normal growth rates in the wake of the lifting of pandemic-related lockdowns last December, misgivings have increased about the party-state’s ability to run the economy.” (ANI)

ALSO READ: Central American Parliament includes China as observer