While leveraging major powers for economic and strategic benefits is a common diplomatic tactic for smaller nations, the risks of over-reliance on China are well-documented in the experiences of Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Pakistan.

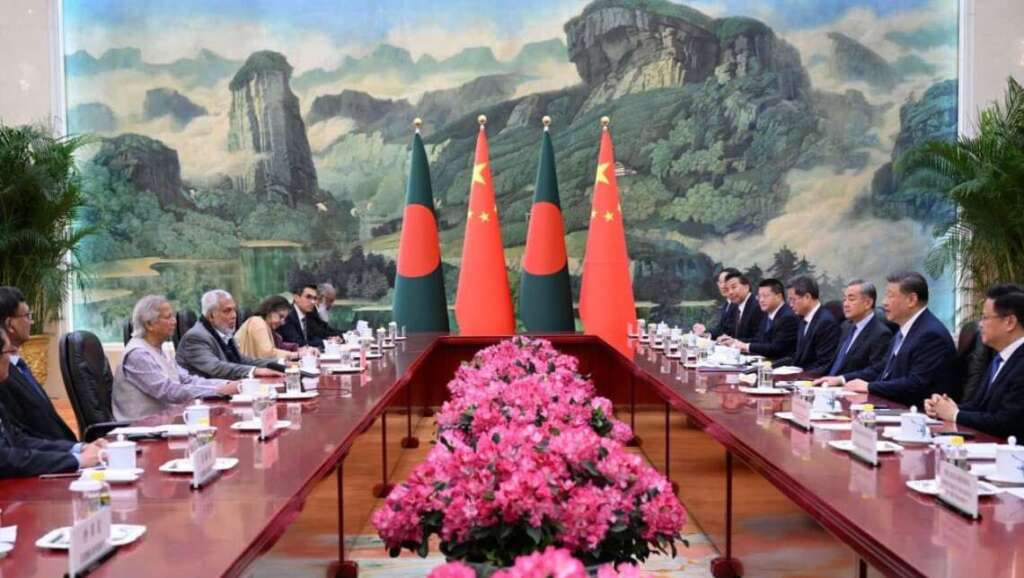

Bangladesh’s interim government Chief Adviser, Professor Muhammad Yunus, is leading a 57-member delegation on a four-day visit to China, underscoring Dhaka’s increasing engagement with Beijing. Yunus has met Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People. His trip, arranged by the Chinese government, signals a shift in Bangladesh’s foreign policy, particularly in light of his apparent diplomatic cooling towards India.

Since assuming office in August 2024, Yunus has yet to visit India, raising concerns about the state of bilateral relations. His growing outreach to China suggests a recalibration of Bangladesh’s strategic priorities, possibly positioning Beijing as a counterweight to New Delhi. While leveraging major powers for economic and strategic benefits is a common diplomatic tactic for smaller nations, the risks of over-reliance on China are well-documented in the experiences of Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and Pakistan.

China’s deep pockets and extensive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments have been a double-edged sword for many nations. While the financial influx supports infrastructure projects, it also raises concerns over debt sustainability and loss of strategic assets. Sri Lanka’s struggles offer a cautionary tale—after borrowing heavily from China for projects like the Hambantota Port, the island nation ultimately had to lease the port to a Chinese company due to its inability to repay loans. The move reinforced fears of debt diplomacy and strategic encroachment.

The Maldives has faced similar economic vulnerabilities. The China-Maldives Free Trade Agreement, signed during former President Abdulla Yameen’s tenure, was intended to enhance trade but ended up exposing the small island nation to mounting debt. The Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) has criticised the agreement, warning that tariff eliminations would allow a flood of Chinese goods, potentially harming local businesses. With billions in outstanding external debt, including a significant portion owed to China, the Maldives now struggles to service repayments.

Pakistan’s experience with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) further illustrates the perils of Chinese financing. While CPEC promised transformative economic growth, the terms of engagement, including high-interest loans and strict repayment conditions, have left Pakistan financially strained. Islamabad now owes an estimated $28.78 billion to Beijing, representing 22% of its external public debt. Critics argue that projects like Gwadar Port have served China’s strategic interests more than Pakistan’s economic development.

Bangladesh’s discussions with China indicate a potential broadening of their partnership beyond economic cooperation to political alignment. Beijing is reportedly urging Dhaka to reaffirm its support for the One-China principle and consider deeper collaboration under President Xi’s Global Development Initiative (GDI). While financial aid remains a priority for Bangladesh, China appears to be positioning itself as a long-term political partner, aligning Dhaka’s foreign policy more closely with Beijing’s global agenda.

Despite these potential benefits, Yunus would do well to tread carefully. Sri Lanka’s economic meltdown, Pakistan’s debt distress, and the Maldives’ trade vulnerabilities all highlight the dangers of unchecked dependency on Chinese investments. Transparency, balanced partnerships, and economic viability should be at the forefront of Bangladesh’s engagements with China to avoid the pitfalls that have ensnared its South Asian counterparts.

As Yunus navigates Bangladesh’s geopolitical future, the key lesson from its neighbours remains clear—economic cooperation with China should be strategic, diversified, and transparent to ensure that national interests are not compromised in the long run.