Visit underscores India’s delicate balancing act between engaging Kabul and avoiding formal recognition of Taliban rule, writes Manoj Menon

The decision to host the Taliban’s acting foreign minister, Amir Khan Muttaqi, in New Delhi this week highlights a calculated shift in India’s approach to Afghanistan. Although India does not officially recognise the Taliban regime, the visit — granted under a temporary UN exemption from international travel restrictions — signals a willingness by New Delhi to engage the authorities in Kabul more directly.

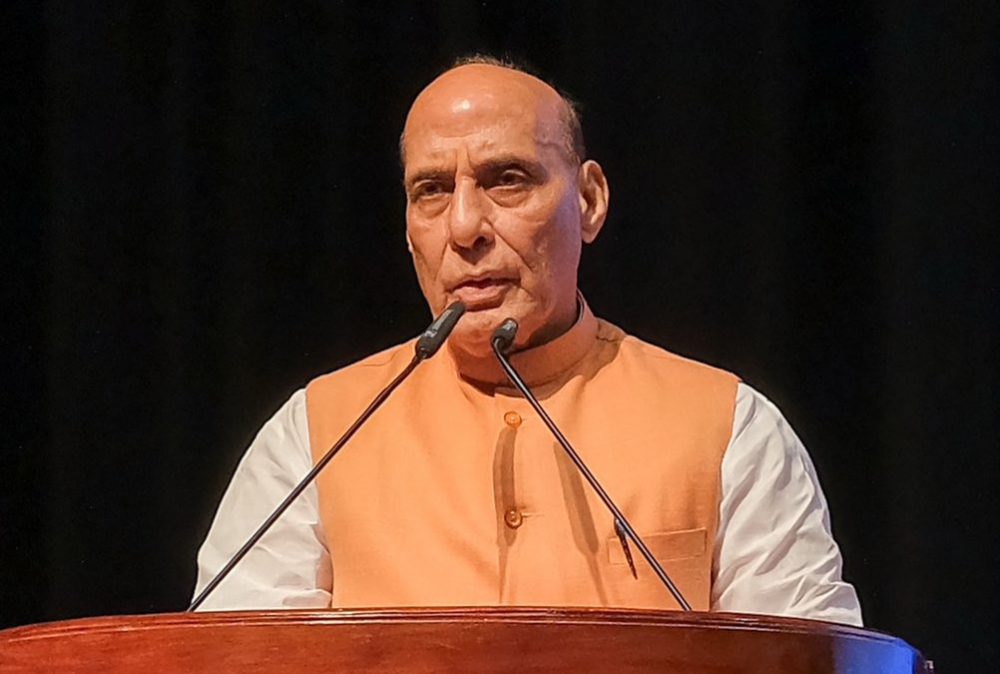

Muttaqi, who is expected to arrive on Thursday for a week-long stay, will meet India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar. Discussions are likely to focus on counterterrorism, trade, and India’s ongoing humanitarian and development assistance to Afghanistan. He is also expected to press New Delhi to permit the posting of an official Taliban envoy at the Afghan embassy in the capital and to expand staffing at Afghan consulates in Mumbai and Hyderabad.

For more than four years, India has adopted a cautious stance — keeping humanitarian channels open while avoiding steps that could be interpreted as diplomatic recognition of the Taliban. This balancing act began shortly after the group seized power in Kabul in August 2021. Ten months later, India sent a “technical team” to Afghanistan to oversee aid distribution and explore avenues of support for the Afghan population, though it refrained from deeper political engagement.

Contacts have nonetheless increased. In November last year, senior Indian official JP Singh held meetings with Taliban representatives, including acting Defence Minister Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob. Earlier this year, veteran diplomat Vikram Misri travelled to Afghanistan, and Muttaqi’s current trip builds on this gradual warming of relations.

Observers note that India’s outreach coincides with worsening ties between Pakistan and the Taliban. Islamabad, long seen as Kabul’s closest ally, has grown frustrated over cross-border militancy and recently launched airstrikes on Afghan territory. For New Delhi, this rift presents both an opportunity and a challenge: it allows India to strengthen its role in Afghanistan while also navigating the risk of inflaming an already volatile regional rivalry.

At the same time, India has joined Pakistan, Russia, and China in signalling opposition to a renewed US military presence in Afghanistan. A joint statement this week described any foreign deployments as “unacceptable” for regional stability — a pointed rebuke to Washington, which had floated the idea of maintaining access to Afghanistan’s Bagram air base.

Indian officials frame their engagement with Kabul largely in developmental terms, pointing to projects in health, education, and infrastructure. Expanding visas for Afghan patients and students is also seen as a way of bolstering people-to-people ties without extending political recognition.

Yet analysts caution that this pragmatic diplomacy cuts both ways. While India gains the chance to re-establish a presence in Kabul and hedge against instability spilling over its borders, it also risks criticism from Western allies and domestic voices concerned about legitimising a government accused of rolling back women’s rights and democratic freedoms.

For New Delhi, then, the significance of Muttaqi’s visit lies less in symbolism and more in strategy. The talks will test how far India can go in building working relations with Afghanistan’s rulers without crossing the line into formal recognition.

The outcome will also be closely watched in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran, all of which maintain varying levels of dialogue with the Taliban. With regional geopolitics in flux, India’s next steps could help determine not only its role in Afghanistan but also its standing among global powers vying for influence in the region.