The refusal of the refugees to return to Myanmar has not come as a surprise…writes Saleem Samad

The million Rohingya refugees living in squalid camps in southeast Bangladesh refused to be resettled into another encampment in Myanmar.

The refusal of the refugees to return to Myanmar has not come as a surprise. They argue that unless Myanmar guarantees their citizenship rights, freedom of movement, access to livelihood, healthcare and education, a sustainable repartition will be half-hearted.

The response by the Rohingya refugees follows Myanmar government’s sudden offer to repatriate by the end of the year 6,000 Rohingya who were regarded as “illegal migrants” in Myanmar.

In persuasion of the repartition offer, a delegation of Rohingya refugees along with Bangladesh government officials recently visited Maungdaw Township and adjoining villages in the Rakhine State resettlement plan.

The settlements were built with support from China, India and Japan. Altogether 3,500 Rohingya will be accommodated in 15 villages, says Rahman.

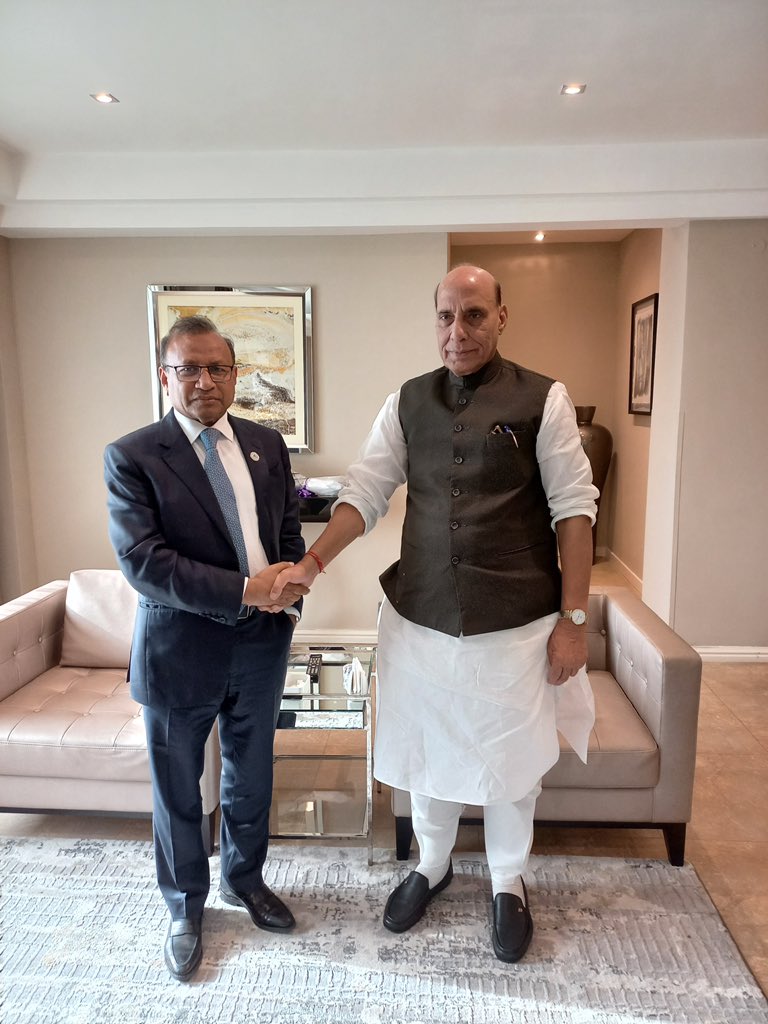

Bangladesh’s Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commissioner (RRRC) in Cox’s Bazar, Mohammed Mizanur Rahman who led the delegation observed that “repatriation was the only solution to end the refugee crisis.”

However, on their return, they expressed dissatisfaction over the arrangements and facilities made by the Myanmar authority.

Myanmar’s capital Naypyidaw conspicuously remain silent over the returnees citizenship rights, but assured that the Rohingya will be given a national verification card (NVC), which the Rohingya refugees regard as too little and too less.

The controversial Citizenship Law of 1982 requires individuals to prove that their ancestors lived in Myanmar before 1823, and refuse to recognise Rohingya Muslims as one of the nation’s ethnic groups or list their language as a national language.

“We don’t want to be confined in resettlement camps,” remarked Oli Hossain, a refugee delegate. He explained that they will never accept NVC, which apparently identifies the Rohingya as ‘aliens’.

Bangladesh authorities also told the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) or UN Refugee Agency, which advocates for the safe, voluntary, dignified and sustainable repatriation of 1.2 million Rohingya refugees who fled the ethno-religious strife in 2017 amid a military crackdown.

The crackdown was sparked after the Islamic jihadist Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) overran a couple of Myanmar Border Guards Forces outposts in August 2017.

Naypyidaw for several years refused to hold dialogue regarding the return of Rohingya, stating that they are not citizens of Myanmar.

Bangladesh has raised the refugee crisis at several international platforms and other global summits. The world leaders lauded Bangladesh leader Sheikh Hasina for providing food and shelter to a million ‘stateless’ Rohingya.

Unfortunately, several attempts to repatriate the refugees fell flat in 2018 and 2019. Instead, Bangladesh blames the intransigent policy of the Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi who was placed under house arrest in February 2021, in the wake of her government’s ouster by military leaders.

Finally, Myanmar’s ‘all-weather friend’ China could pursue Naypyidaw to renew the negotiation on repartition.

Recently, at a critical tripartite meeting of the Foreign Ministry officials between Bangladesh, China and Myanmar in Kunming, despite reservation from the UN Human Rights Office and UN Refugee Agency that Rakhine State is unsafe for repatriation.

Beijing has a crucial regional agenda and several mega Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects are in progress with Naypyidaw.

Some hiccups have emerged in ties between Bangladesh and China especially after Dhaka gave a thumbs-up to join the Indo-Pacific security axis.

Furthermore, Bangladesh has cancelled the deep-sea port in the Bay of Bengal, a multi-purpose barrage over the Teesta River and a couple of other projects after India raised objections.

Researchers on forced migration said they do not see any light at the end of the tunnel for the refugees to return to their homes by the end of this year.

(The content is being carried under an arrangement with indianarrative.com)

ALSO READ: